Berkshire Hathaway at $600,000

A look at Berkshire's recent stock price advance in the context of repurchase activity and commonly used valuation metrics.

Note to Readers: I have always been reluctant to comment on stock prices and I never provide investment advice. However, I have a few observations to share in this article about Berkshire Hathaway’s recent stock price advance. The company’s annual report along with Warren Buffett’s letter to shareholders will be released on Saturday morning. I will publish additional articles following the annual report release.

Introduction

Last year, Berkshire Hathaway reached a milestone when its market capitalization exceeded $800 billion. Those of us who think like business owners tend to focus on a company’s market capitalization. However, traders and the majority of stock market investors focus on a company’s price per share. This explains the excitement when Berkshire’s Class A stock reached and surpassed the $600,000 milestone last week.

On Friday, February 16, Berkshire’s Class A stock closed at $610,086 and the Class B stock closed at $405.99. The Class B discount, which widened to historically high levels last year, has almost disappeared and now stands at 0.2%.1 Berkshire’s market capitalization, excluding the impact of repurchases since September 30, 2023, stands at ~$882 billion.2 For those looking forward to Berkshire joining the trillion dollar market cap club, keep an eye out for ~$692,000 on the Class A shares.

Berkshire has had quite a run over the past year with the Class A shares rising 30.6%. While it is certain that the company’s intrinsic value has increased over the past year, there is no possibility that intrinsic value has increased by as much as the stock price.

The stock has clearly outperformed the business over the past year.

A company’s stock price does not track underlying business value over short periods of time such as a year or even a couple of years. Over five or more years, however, the stock will tend to roughly track the financial results of the business.

If one accepts that intrinsic value could not have increased by 30% over the past year, does this make the stock overvalued? Not necessarily, because shares could have been undervalued at this time last year. There are good reasons to believe that this was the case based on recent repurchase activity that has been publicly disclosed.

Repurchase Activity

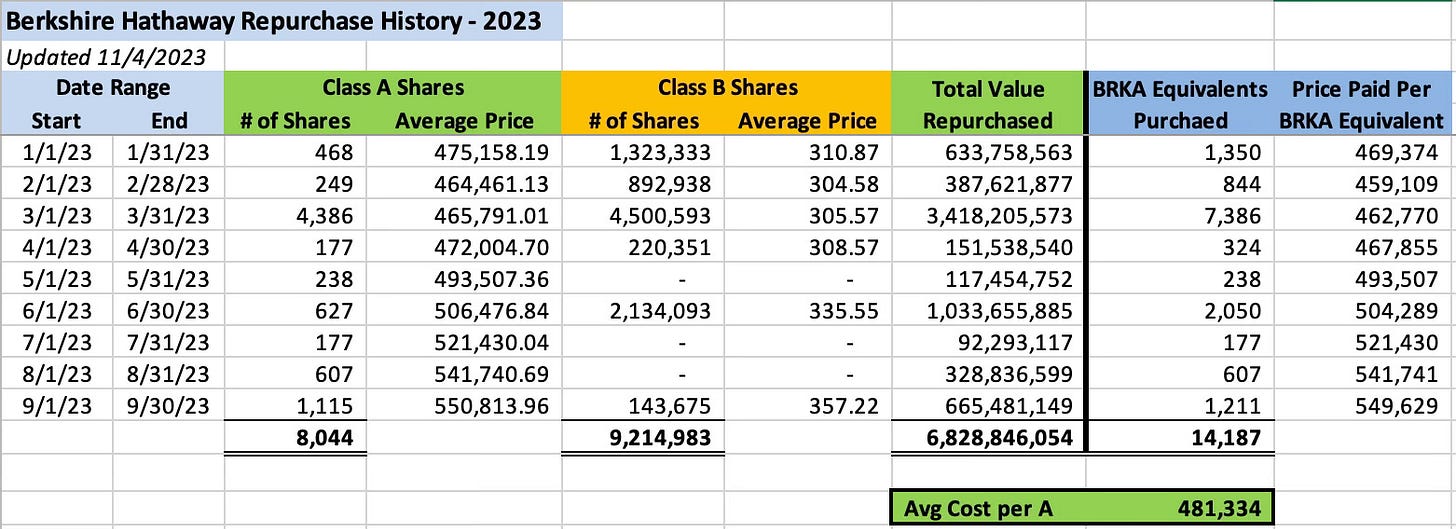

During the first nine months of 2023, Warren Buffett allocated $6,829 million to repurchase 14,187 Class A equivalents which works out to an average price of $481,334 per share. Repurchase activity for the first nine months of 2023 is shown in the exhibit below which first appeared in my article reviewing third quarter results:

It should not be surprising that repurchase activity slowed down later in the year as the stock price advanced. Berkshire only used $1,087 million for repurchases during the third quarter. Based on the third quarter 10-Q filing, we know that repurchase activity continued into the early fourth quarter, as I noted in my article:

We know that repurchase activity continued in October because the updated share count appearing on the first page of Berkshire’s third quarter 10-Q. As of October 24, there were 1,444,002 Class A equivalent shares outstanding compared to 1,445,546 shares outstanding as of September 30. This implies repurchases of 1,544 Class A equivalents over the first seventeen trading days of October. Over this period, the average closing price of Class A shares was approximately $522,200 so we can very roughly estimate that $800 million was used for repurchases from October 1 to 24.

How many shares were repurchased in total in the fourth quarter? Did repurchase activity continue into 2024? These are questions that we will not be able to answer until Saturday, February 24. The annual report will reveal the full repurchase record for 2023 along with a more recent share count from which we will be able to infer whether there were repurchases between January 1 and sometime in mid-February.

Most companies with repurchase programs seem to buy back shares with little awareness of the stock price relative to intrinsic value, but this has never been the case at Berkshire Hathaway. Here is Berkshire’s policy regarding repurchases:

“Berkshire’s common stock repurchase program, as amended, permits Berkshire to repurchase shares any time that Warren Buffett, Berkshire’s Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, and Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of the Board, believe that the repurchase price is below Berkshire’s intrinsic value, conservatively determined. The program continues to allow share repurchases in the open market or through privately negotiated transactions and does not specify a maximum number of shares to be repurchased. However, repurchases will not be made if they would reduce the total value of Berkshire’s consolidated cash, cash equivalents and U.S. Treasury Bill holdings below $30 billion. The repurchase program does not obligate Berkshire to repurchase any specific dollar amount or number of Class A or Class B shares and there is no expiration date to the program.” [Emphasis added]

When we read the words “conservatively determined”, should we take this seriously and, if so, can we estimate what level of discount is required to induce Warren Buffett to repurchase stock?

I think we should take those words very seriously.

Repurchases made above intrinsic value have the effect of destroying shareholder value compared to retaining the cash or paying a dividend. Nearly all of Warren Buffett’s wealth is invested in Berkshire stock. A value destroying repurchase program would harm him more than anyone else. At most companies, there are incentives to boost the stock price in the short run. Since no one, including Mr. Buffett, receives stock based compensation, this perverse incentive is absent at Berkshire.

In September 2023, Berkshire repurchased 1,211 Class A equivalents at an average cost of $549,629 per share which is almost exactly 10% below the current price.

It seems to me that “conservatively determined” would include a margin of safety of at least 10% and probably quite a bit more. It is very doubtful that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger would have viewed Berkshire’s Class A shares at $610,000 to be crazy if they were repurchasing shares in September 2023 around $550,000.

Although it seems highly unlikely that Warren Buffett would consider Berkshire’s current stock price to be crazy, it would not surprise me if he slows or halts repurchase activity in response to such a significant rally. He might think that Berkshire is still trading below intrinsic value, albeit not conservatively determined, or he could regard the stock price as somewhat above intrinsic value. Although quite unlikely, he might also have a major acquisition in his sights that he thinks will provide better returns than repurchases of Berkshire stock at current levels.

The reality is that no one, including Warren Buffett, can precisely calculate intrinsic value. The best that anyone can do is to look at the business and come up with a range of reasonable valuations, and to repurchase stock only when it trades at a discount to the lower range of reasonable value estimates. I suspect that the stock now trades within a “zone of reasonableness” that could cause repurchase activity to slow or stop, but this is a far cry from considering shares overvalued. The difference between the current price and the price paid for past repurchases is too narrow to conclude that the shares are currently overvalued, at least in Mr. Buffett’s opinion.3

Price-to-Book Ratio

Starting in 2019, Berkshire Hathaway’s annual reports no longer make explicit mention of book value for reasons that were explained at length in Warren Buffett’s 2018 annual letter which I commented on in Warren Buffett Moves the Goalposts. For a number of reasons, the positive gap between intrinsic value and book value has grown over time. Readers interested in more details regarding why book value is no longer as useful as it was in the past are encouraged to refer to the links above.

Although book value has become distorted over time, many shareholders still track Berkshire’s price-to-book ratio. As of September 30, 2023, Berkshire’s book value per Class A share stood at $363,413. Using September 30, 2023 book value, the shares currently trade at 1.68x book value, although a likely increase in book value as of December 31, 2023 will lower this figure when we receive the 2023 annual report.

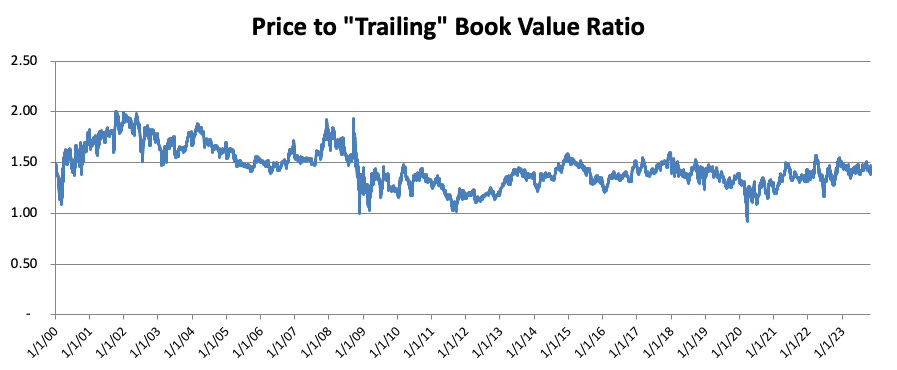

For many years, I have tracked Berkshire’s price-to-book ratio, which has been updated through the end of the third quarter of 2023 in the chart below:

Berkshire’s current price-to-book ratio is indeed elevated compared to levels that have prevailed since the financial crisis of 2008-09.

During the vast majority of the past fifteen years, Berkshire’s stock price has ranged between 1.1x and 1.5x of its “trailing” book value. From around 2001 to the start of the financial crisis, Berkshire’s price ranged mostly between 1.5x and 2.0x book value.

Following the financial crisis, at least on this admittedly crude valuation metric, Berkshire suffered a downward re-rating that persisted for a very long time — far longer than I expected — all during a period in which the gap between book value and intrinsic value was arguably growing steadily.

In my opinion, the elevated price to-book ratio, relative to the recent past, is not necessarily a sign of overvaluation in light of the widening positive gap between intrinsic value and book value which should logically result in a higher price-to-book ratio over long periods of time.

Two Column Method

Another Berkshire valuation method with a very long history is known as the “two column” approach. The underpinning of this approach is based, in part, on comments Warren Buffett has made, including this except from his 2008 letter to shareholders:

“Berkshire has two major areas of value. The first is our investments: stocks, bonds and cash equivalents. At yearend those totaled $122 billion (not counting the investments held by our finance and utility operations, which we assign to our second bucket of value). About $58.5 billion of that total is funded by our insurance float.

Berkshire’s second component of value is earnings that come from sources other than investments and insurance. These earnings are delivered by our 67 non-insurance companies, itemized on page 96. We exclude our insurance earnings from this calculation because the value of our insurance operation comes from the investable funds it generates, and we have already included this factor in our first bucket.”

Bucket #1: As of September 30, 2023, Berkshire had cash and consolidated investments of $520.5 billion, excluding cash and investments held by the railroad and utility businesses.

Bucket #2: Pre-tax earnings for non-insurance subsidiaries for the four quarters ending on September 30, 2023 came in at $25.1 billion. To this figure, I think it is appropriate to add an estimate of “normalized” underwriting profits of $1.5 billion. I estimate this figure based on an average of five years of pre-tax underwriting profits. This results in $26.6 billion of pre-tax earnings.4

Rather than stating my opinion of an appropriate multiple of pre-tax earnings, let’s see what Berkshire’s current market capitalization of $882 billion implies:

Let x = Implied Pre-tax earnings multiple

Market Cap = Bucket #1 + Bucket #2

882 = 520.5 + (26.6x)

26.6x = 361.5

x = 13.6

So, to arrive at Berkshire’s market capitalization, we can infer a multiple of 13.6 on trailing pre-tax earnings for the four quarters ending on September 30, 2023.

It would be possible to estimate a more current value for Bucket #1 by examining Berkshire’s recently released 13-F filing disclosing positions at December 31, 2023 and guessing the company’s yearend cash balance. However, since the annual report will be out in a few days and this current exercise is not meant to be precise, I have used the published figures from September 30, 2023.

It’s important to acknowledge that a portion of Berkshire’s investments are funded with insurance policyholder float which totaled $167 billion as of September 30, 2023. One could argue that we must deduct this liability, but the premise of the two-column approach is that float is unlikely to decline, at least not rapidly, and that Berkshire will break even on underwriting, on average, in the future. As long as those conditions hold, Berkshire’s float is akin to an interest-free loan in perpetuity; indeed, better than an interest free loan to the extent that insurance operations underwrite at a profit.5

Assuming one buys into the premise of the two-column valuation method, is 13.6x pre-tax earnings an insane multiple? It would be difficult to make the case that this multiple is insane especially in light of the valuation of the overall stock market.

Another question is whether Berkshire’s marketable securities are overvalued, particularly the immensely large stake in Apple. I cannot answer this question for readers, but it is easy to “haircut” suspect positions if desired and incorporate this reduction into Bucket #1.

My purpose is not to pinpoint a valuation of Berkshire using the two-column approach, only to suggest that shareholders who buy into the premise behind it can use it as a tool to gauge whether the stock is trading in a zone of reasonableness. One only needs to judge whether the investments appear to be reasonably valued and to decide on a reasonable multiple of pre-tax non-insurance operating earnings.

Using this approach, it seems difficult to argue that the stock is very overvalued unless one believes the equity portfolio to be grossly overvalued, believes that non-insurance operating earnings are unsustainably high, or opts to use a low multiple of pre-tax operating earnings in the calculation.

Conclusion

We should be aware of psychological dangers when it comes to advancing stock prices, especially related to round numbers like $600,000 for the Class A shares or $400 for the Class B shares. These round numbers are, of course, meaningless in terms of determining whether the stock is cheap, fairly valued, or expensive. However, the human mind often anchors on round numbers.

Value investors often have a tendency of sticking with stocks for long periods of time while they are clearly undervalued only to employ a hair-trigger on sell decisions when a stock seems to be approaching fair value. I have made this mistake many times over my investing career, with my sale of Microsoft being the most painful example. This hair trigger approach of selling just as a reasonable valuation is reached can be a terrible mistake when dealing with an excellent underlying business that is highly likely to grow intrinsic value in the future.

Some value investors employ a strategy of buying deeply undervalued stocks and selling just as intrinsic value approaches. This could be a fine strategy if one has a list of deeply undervalued stocks to deploy the after-tax proceeds of a sale, but there is also much to be said for a more passive coffee can style approach to investing.

I am looking forward to reading Berkshire’s upcoming annual report and Warren Buffett’s letter to shareholders and sharing my thoughts with subscribers.

If you found this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider sharing it with your friends and colleagues.

Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Individuals associated with The Rational Walk own shares of Berkshire Hathaway.

Class B shares have economic rights equivalent to 1/1500th of a Class A share and voting rights equivalent to 1/10000th of a Class A share: Warren Buffett’s memo of 1/20/2010

Market capitalization estimated based on Class A equivalents and the last Class A quote.

The disappearance of the Class B discount could be the result of Berkshire’s absence in the market for Class A shares. I believe that Warren Buffett prefers to repurchase Class A shares since doing so enhances the voting power of remaining Class A shareholders. If this theory is correct, the disappearance of the Class B discount could be due to a reduction or absence of buying demand by Berkshire in 2024. However, this theory is speculative.

I can defend adding normalized underwriting profits despite their origination in the insurance business because such profits are not accounted for in the first bucket. The implicit assumption of the model is that underwriting occurs at break-even levels, but at Berkshire there have been consistent underwriting profits over many decades. It is easy enough to exclude normalized underwriting profits if more conservatism is desired.

The same criticism applies to the deferred tax liability on Berkshire’s investments. If one regards the majority of Berkshire’s portfolio as quasi-permanent in nature, and there are good reasons to believe this is the case, the deferred tax liability functions as an interest free loan until the securities in question are sold. That being said, taxes will eventually come due so some shareholders choose to deduct a portion of the deferred tax liability.

Nice write up!

$1 trillion market cap and $1 million price for the A-shares will be two very special milestones for Warren, even if they are arbitrary.