Warren Buffett on Inflation — Part 3

During periods of high inflation, capital-light businesses have important advantages

The passage of time plays tricks on our memories. Agonizingly slow trials and tribulations in the present appear less extreme when viewed retrospectively.

The historical narrative of the inflation that took hold from the middle of the 1960s to the early 1980s is told knowing that Paul Volcker would have the fortitude to dispense the medicine needed to finally break the fever. However, people who actually lived through those years had no such advance knowledge and conventional wisdom was that high inflation would persist in the 1980s and perhaps indefinitely.

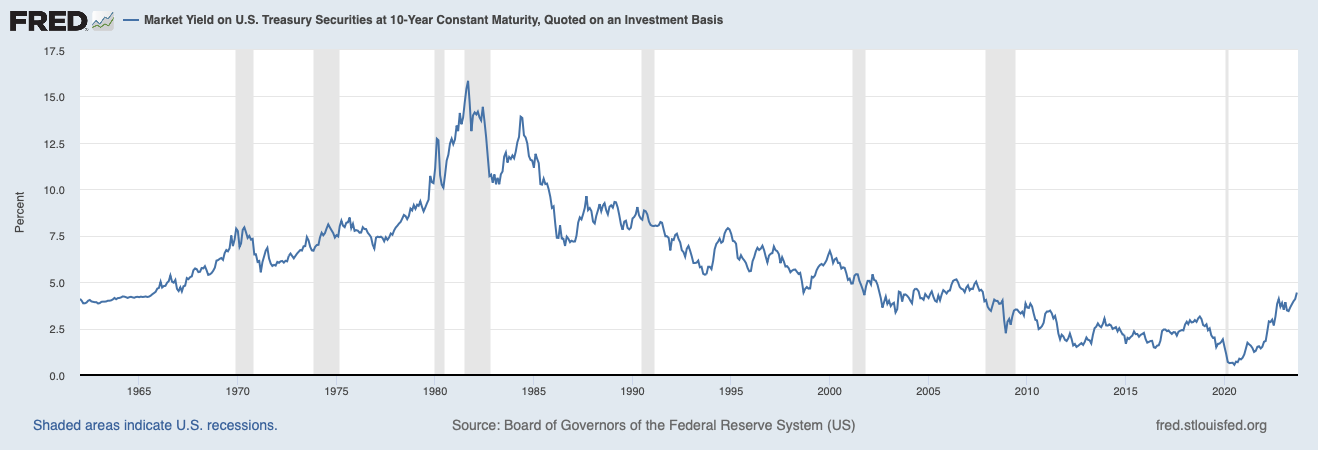

Long term treasuries yielded above 15% in 1981 in anticipation of years of high inflation. When the rate of inflation started to decline, interest rates remained relatively high for many years as market participants remained skeptical.

The exhibit below shows the yield on the ten year treasury since 1962. What’s interesting about the chart is that the current ten year yield of around 4.5% is comparable to yields seen in the mid-1960s and remains very low from a historical perspective. Many charts published in the financial media seem to start around 2005 which creates the false illusion that current rates are historically high.

Double-digit inflation did not return after the spike of the early-1980s and yields began a long multi-decade decline. This decline was hardly in a straight line and those who actually lived through the upward squiggles in the chart could very well have declared the end of the bond bull market at numerous times. In the 1980s, anyone who predicted that the ten year treasury would eventually yield under 1% in 2020 might have been involuntarily committed to a mental institution for observation.

Even Warren Buffett was surprised by the taming of inflation during the 1980s based on comments in his shareholder letters. In early 1987, Mr. Buffett was still expecting a return to higher levels of inflation when he wrote about his distaste for long-term bonds, predicting “much higher rates of inflation within the next decade.”

While I personally recall the later years of the Great Inflation, the extent of my dismay was mostly restricted to feeling cheated when comic books went from 40 cents to a shocking 75 cents over just a few years. But fortunately, reading provides a window to the past as seen through the eyes of people who lived through it.

I’ve read Warren Buffett’s letters to shareholders sequentially many times. By doing so we can see how Berkshire Hathaway evolved over the decades in “real-time” rather than with the benefit of hindsight. My interest in reading about the Great Inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s recently inspired a return to the letters of that period.

Links to the first two articles in this series appear below. Part one covers Mr. Buffett’s views on bonds and interest rates in early 1970. Part two is an overview of how Berkshire’s auto insurance business was caught by surprise during the mid-1970s. In this article, I will focus on Warren Buffett’s comments regarding the great advantage of owning capital-light businesses with pricing power during inflationary times.

False Comfort

“For years the traditional wisdom – long on tradition, short on wisdom – held that inflation protection was best provided by businesses laden with natural resources, plants and machinery, or other tangible assets (‘In Goods We Trust’). It doesn’t work that way. Asset-heavy businesses generally earn low rates of return – rates that often barely provide enough capital to fund the inflationary needs of the existing business, with nothing left over for real growth, for distribution to owners, or for acquisition of new businesses.”

— Warren Buffett, Appendix to 1983 letter to shareholders

Generations of Benjamin Graham’s disciples have started with the balance sheet when analyzing a business. The quest for companies trading at less than book value, or better yet, below net current asset value, has long been viewed as the cornerstone of intelligent investing. This was true for Warren Buffett for a long time and he had great success with investments such as Dempster Mill during the partnership years, and this is what led Mr. Buffett to acquire control of Berkshire Hathaway itself.

Of course, aside from liquidation scenarios, the analyst must closely examine the income statement over many years to be satisfied that the enterprise is capable of earning an adequate return on equity. A poor business incapable of earning an adequate return on equity will justifiably see its stock trade below book value since buyers will demand an adequate return on their investment. In contrast, a great business that delivers a return on equity far in excess of the average business can be expected to trade far above book value.

With Charlie Munger’s help, Warren Buffett began to shift his attention toward intangible assets in the early 1970s. As Mr. Munger pointed out decades later, it is difficult to move away from an approach that had worked so well for so long:

“I don’t love Ben Graham and his ideas the way Warren does. You have to understand, to Warren — who discovered him at such a young age and then went to work for him — Ben Graham’s insights changed his whole life, and he spent much of his early years worshiping the master at close range. But I have to say, Ben Graham had a lot to learn as an investor. His ideas of how to value companies were all shaped by how the Great Crash and the Depression almost destroyed him, and he was always a little afraid of what the market can do. It left him with an aftermath of fear for the rest of his life, and all his methods were designed to keep that at bay.”

What worked so well for Ben Graham in depression-era markets, and continued working well for Warren Buffett as he started his career in the 1950s, would not work nearly as well in the inflationary environment of the late 1970s. In his 1983 letter to shareholders, Mr. Buffett contrasts asset-heavy enterprises with companies that have significant intangible assets and minimal need for tangible assets:

“In contrast, a disproportionate number of the great business fortunes built up during the inflationary years arose from ownership of operations that combined intangibles of lasting value with relatively minor requirements for tangible assets. In such cases earnings have bounded upward in nominal dollars, and these dollars have been largely available for the acquisition of additional businesses. This phenomenon has been particularly evident in the communications business. That business has required little in the way of tangible investment – yet its franchises have endured. During inflation, Goodwill is the gift that keeps giving.”

Economic goodwill is not an asset that can be estimated with great precision. When accounting goodwill exists on a balance sheet, it is the result of a business acquisition that was made for a sum greater than the identifiable assets of the acquired business. In 1983, accounting goodwill was subject to amortization over forty years.1 However, as Mr. Buffett explained in the letter, the economic goodwill of an excellent business is more likely to grow over time than to shrink.

Many businesses with significant economic goodwill have no accounting goodwill on their balance sheet. A start-up that generates economic goodwill over time will not have any balance sheet account for goodwill. It is only when a business is acquired that accounting goodwill will appear on the balance sheet of the purchaser.

It seems intuitive that one would want to own businesses with a large amount of tangible assets during inflationary times based on the idea that those tangible assets should be worth more after taking the effects of inflation into account. But favoring businesses with a great deal of tangible assets just because they are visible on the balance sheet is a false comfort.

See’s Candies vs. “A Mundane Business”

During my childhood in California, no holiday season was complete without at least a few boxes of See’s Candies. For those who have never lived in California, it’s difficult to understand the formidable brand that See’s had developed by the 1970s. The only negative was that few people would eat See’s year round. It was very much a candy for special occasions, but this also meant that customers were not very price sensitive.

By 1983, Berkshire Hathaway had owned See’s Candies for over a decade and Warren Buffett reflected on the company’s economics in the appendix to his 1983 letter to shareholders. The unexciting title of the appendix is “Goodwill and its Amortization: The Rules and The Realities” which probably deterred many readers from proceeding. But the appendix is really about the benefits of companies with economic goodwill during inflationary times — a far more exciting topic — with See’s as a case study.

When Blue Chip Stamps acquired See’s Candies in 1972 for $25 million, See’s had $8 million of net tangible assets and was earning $2 million after tax.2 When Berkshire paid $17 million over net tangible assets, this generated $17 million of accounting goodwill that was slowly amortized into expenses over many years.

Obviously, it would have been wonderful to purchase a business earning $2 million after tax for just $8 million. However, the ability of a business to earn 25% after tax on net tangible assets obviously indicated the presence of valuable economic goodwill. Although Mr. Buffett might have considered paying $25 million for a business earning $2 million to be a rich price, Charlie Munger was more willing to consider intangible assets and was strongly in favor of the purchase.

Warren Buffett explained the purchase rationale as follows:

“In 1972 (and now) [early 1984] relatively few businesses could be expected to consistently earn the 25% after tax on net tangible assets that was earned by See’s – doing it, furthermore, with conservative accounting and no financial leverage. It was not the fair market value of the inventories, receivables or fixed assets that produced the premium rates of return. Rather it was a combination of intangible assets, particularly a pervasive favorable reputation with consumers based upon countless pleasant experiences they have had with both product and personnel.

Such a reputation creates a consumer franchise that allows the value of the product to the purchaser, rather than its production cost, to be the major determinant of selling price. Consumer franchises are a prime source of economic Goodwill. Other sources include governmental franchises not subject to profit regulation, such as television stations, and an enduring position as the low cost producer in an industry.”

In 1983, See’s earned $13.7 million after taxes on $20 million of net tangible assets. In other words, See’s went from earning 25% on net tangible assets to 68.5% over eleven years. As Mr. Buffett points out, this indicates the presence of economic goodwill far larger than the original cost of accounting goodwill.

See’s produced extraordinary results during a period of high inflation, as we can see from the following table from the 1983 shareholder letter:

It is remarkable that a company that generated $31.3 million of sales in 1972 using $8 million of net tangible assets could generate $133.5 million of sales in 1983 using just $20 million of net tangible assets. We can see from the table that See’s had very strong pricing power throughout this period. The implied price per pound rose from $1.85 in 1972 to $5.42 in 1983. Although physical volume of candy sales slowed toward the end of the period, price increases continued to deliver enhanced profitability.

Warren Buffett presents readers with a thought experiment comparing the purchase of See’s Candies in 1972 to a hypothetical “mundane” business:

“… Let’s contrast a See’s kind of business with a more mundane business. When we purchased See’s in 1972, it will be recalled, it was earning about $2 million on $8 million of net tangible assets. Let us assume that our hypothetical mundane business then had $2 million of earnings also, but needed $18 million in net tangible assets for normal operations. Earning only 11% on required tangible assets, that mundane business would possess little or no economic Goodwill.

A business like that, therefore, might well have sold for the value of its net tangible assets, or for $18 million. In contrast, we paid $25 million for See’s, even though it had no more in earnings and less than half as much in ‘honest-to-God’ assets. Could less really have been more, as our purchase price implied? The answer is ‘yes’ – even if both businesses were expected to have flat unit volume – as long as you anticipated, as we did in 1972, a world of continuous inflation.”

The following summary shows the scenario described above in tabular form:

It is doubtful that an investor rigidly applying Benjamin Graham’s principles would buy either company, but if forced to choose, such an investor would almost certainly prefer the mundane business given that it could be purchased at book value, implying a larger margin of safety, and provided a higher initial return on the purchase price.

My initial reaction when reading this section was that the missing element is that See’s could be expected to grow while the “mundane” business might not. However, Mr. Buffett explains how See’s represented greater value in “a world of continuous inflation” even if both businesses were expected to have flat unit volume.

If we assume that the price level doubles, how would this affect these businesses? They would both need to double nominal earnings to $4 million to represent flat earnings in real terms. If each business could maintain the same unit volume while doubling prices, profits would also double assuming that margins stay the same.

But there is crucial difference:

“But, crucially, to bring that about, both businesses probably would have to double their nominal investment in net tangible assets, since that is the kind of economic requirement that inflation usually imposes on businesses, both good and bad. A doubling of dollar sales means correspondingly more dollars must be employed immediately in receivables and inventories. Dollars employed in fixed assets will respond more slowly to inflation, but probably just as surely. And all of this inflation-required investment will produce no improvement in rate of return. The motivation for this investment is the survival of the business, not the prosperity of the owner.”

In the table below, I have summarized the scenario for the two businesses following the doubling of the price level:

Both See’s Candies and the mundane business must double net tangible assets in order to double after-tax earnings. However, See’s only requires an incremental $8 million of investment while the mundane business requires $18 million. Under this scenario, we can expect that the market value of both businesses would double. However, See’s only had to invest $8 million in incremental net tangible assets to generate $25 million of incremental market value. In contrast, the mundane business invested $18 million to generate $18 million of incremental market value.

What kind of alchemy can convert $8 million of additional investment into $25 million of market value? The answer is the presence of economic goodwill. Economic goodwill doubled from $17 million to $34 million, but this doubling required not a single dollar of incremental capital investment. The value of the goodwill kept up with inflation but required no capital investment from the owners of the business.

Conclusion

See’s Candies was not only a dream business for Berkshire from an economic perspective but represented a real-life case study that changed Warren Buffett’s approach to capital allocation in the half century that followed. Of course, Charlie Munger’s insight played a major role in bringing about this transformation.

In his 2007 letter to shareholders, Mr. Buffett reported that See’s generated $383 million of sales with pre-tax profits of $82 million. Remarkably, the capital required to run the business was only $40 million. Only $32 million in incremental capital had to be invested between 1972 and 2007 to handle the growth of the business. Cumulative pre-tax profits on that initial $25 million purchase totaled $1.35 billion, with all of that cash sent to Berkshire to acquire other businesses. Unfortunately, companies with the economics of See’s Candies are few and far between:

“There aren’t many See’s in Corporate America. Typically, companies that increase their earnings from $5 million to $82 million require, say, $400 million or so of capital investment to finance their growth. That’s because growing businesses have both working capital needs that increase in proportion to sales growth and significant requirements for fixed asset investments.

A company that needs large increases in capital to engender its growth may well prove to be a satisfactory investment. There is, to follow through on our example, nothing shabby about earning $82 million pre-tax on $400 million of net tangible assets. But that equation for the owner is vastly different from the See’s situation. It’s far better to have an ever-increasing stream of earnings with virtually no major capital requirements. Ask Microsoft or Google.”

See Candies is a tremendous business but has proven to be quite limited in terms of growth opportunities beyond the west coast. If See’s had the ability to generate its returns on tangible assets while also being able to reinvest those earnings at the same rate, it would be a compounding powerhouse. Instead, it has been a cash cow for Berkshire and fueled acquisitions in totally different fields.

It seems fitting to conclude by noting that Warren Buffett did not have perfect foresight when it came to predicting the Great Inflation or the disinflation of the 1980s. In fact, he clearly expected high inflation to persist into the 1980s and beyond. But nailing a macro forecast was not required for Berkshire Hathaway to thrive.

If you found this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider referring a friend to The Rational Walk.

Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

The rules for accounting goodwill have changed several times over the years. Currently, accounting goodwill is not subject to periodic amortization. Instead, accountants are supposed to “test” their operations for whether goodwill has been impaired. If the current estimate of economic goodwill is less than accounting goodwill, a charge to earnings must be taken. The reverse is never true: if a business has growing economic goodwill, no balance sheet account is ever inflated to recognize such an estimate.

In 1972, Blue Chip stamps was controlled by Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger. Blue Chip was eventually merged into Berkshire Hathaway in 1983.