Warren Buffett on Inflation — Part 1

Lessons from the final Buffett Partnership letters

“I should note that the cemetery for seers has a huge section set aside for macro forecasters. We have in fact made few macro forecasts at Berkshire, and we have seldom seen others make them with sustained success.”

Introduction

One of the enduring misconceptions among investors is that Warren Buffett ignores the macroeconomy. To the contrary, a careful reading of Mr. Buffett’s shareholder letters over many decades makes it clear that he closely monitors macroeconomic conditions. It is more accurate to say that Berkshire Hathaway rarely makes bets directly on macroeconomic factors. This does not mean that Mr. Buffett ignores the likely effect of macroeconomic developments on individual businesses when he makes investments or strategic decisions regarding Berkshire’s current businesses.

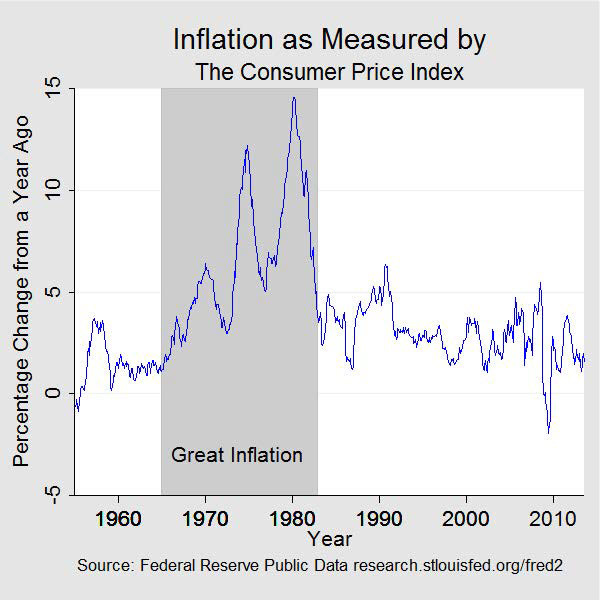

I recently purchased a compilation of Warren Buffett’s shareholder letters from 1965 to 2022. In addition to containing letters prior to 1977, which are not available on Berkshire’s website, the ebook can be easily searched for keywords such as inflation. This proved useful as I went through the letters to better understand Warren Buffett’s thinking about inflation from the 1970s to the early 1980s, an infamous period known as The Great Inflation, as shown in the chart below:

We can see that rising inflation was a constant macroeconomic problem from the time that Warren Buffett took control of Berkshire Hathaway in 1965 until the early 1980s. Despite his brilliance, Mr. Buffett is not omniscient and he is unable to look into a crystal ball to make predictions about the future of the macroeconomy.

In part one of this series, I present observations based on Warren Buffett’s final partnership letter which was meant to provide investment counsel to partners with income needs who wished to invest part of their proceeds in bonds. In part two of the series, I will discuss statements made in Mr. Buffett’s shareholder letters from the 1970s and 1980s as inflation accelerated and finally receded.

We can learn a great deal from the letters, both in terms of subsequent developments in the economy and the limits of Warren Buffett’s ability to make macro forecasts. Despite his inability to accurately forecast inflation and interest rates, tasks that would have been virtually impossible, Berkshire Hathaway obviously delivered excellent returns to shareholders with investments in securities and businesses made in full awareness of the potential impact of inflation at a microeconomic level.

Final Partnership Letters

I found it useful to start my review with the final Buffett Partnership letter, dated February 25, 1970, which was written to educate partners regarding bonds.1

In the letter, Mr. Buffett was clear that his statements represented his view of bonds at that point in time and that he would not provide ongoing investment counseling services. The goal was to recommend sound issues, mostly in the tax-exempt sector, that partners could hold for a long period of time, ideally until maturity. He took great pains to educate partners regarding the risks of investing in bonds, especially the risk of loss if interest rates rise and the bond is sold prior to maturity.2

The entire letter is excellent and the basic mechanics of investing in bonds remain true to this day. However, since my focus in this article is on inflation, I’ll restrict my commentary to that subject rather than on other topics included in the letter, such as the pros and cons of tax exempt bonds, the risks of callable bonds, and bond selection.

Partners were asked for their maturity preference within the ten to twenty-five year range. Partners who were not comfortable with this maturity range or wanted to purchase convertible bonds, corporate bonds, callable bonds, or bonds with a shorter term maturity would have to seek counsel elsewhere. Mr. Buffett noted at the end of the letter that “it looks as if we will have no difficulty in getting in the area of 6-1/2% after tax (except for Housing Authority issues) on bonds in the twenty-year maturity range.”

If an investor had purchased a twenty year tax-exempt bond at par paying a 6.5% coupon in March 1970 and held to maturity in March 1990, he would have received a 6.5% yield over the two decades along with a return of his principal at maturity, assuming no defaults. The problem is that, over the two decade span, inflation compounded at ~6.3% annually according to the BLS CPI Inflation Calculator.3

This experience would obviously be far from ideal since coupon payments would buy steadily less goods and services every year and the principal upon maturity in 1990 would have been diminished by more than 70% compared to purchasing power in 1970. The situation would have been even worse if the investor decided to sell the bond at a loss after ten years, at the height of the great inflation, when prevailing interest rates were far higher than at the time of purchase. Mr. Buffett warned about these risks in his letter, particularly interest rate risk for bonds sold prior to maturity.

As always, Mr. Buffett displayed a great deal of modesty in terms of his ability to forecast the future, in this case the future level of interest rates:

“The second factor in determining maturity selection is expectations regarding future rate levels. Anyone who has done much predicting in this field has tended to look very foolish very fast. I did not regard rates as unattractive one year ago, and I was proved very wrong almost immediately. I believe present rates are not unattractive and I may look foolish again. Nevertheless, a decision has to be made and you can make just as great a mistake if you buy short term securities now and rates available on reinvestment in a few years are much lower.”4

With the benefit of perfect hindsight, it would have clearly been better to keep maturities shorter in the early 1970s due to the onslaught of inflation that was soon to come. Given the upward sloping yield curve at the time, investors would have suffered a yield penalty in the short run in exchange for lower interest rate risk and the ability to reinvest at higher yields later in the decade.

Mr. Buffett explains that interest rates on tax-free bonds had risen for over two decades and this had hurt buyers of long-term bonds, but this did not necessarily mean that the trend toward higher rates would continue. Assuming the yield curve remains positive and without perfect insight into the level of rates, his conclusion was that buying long term non-callable bonds was a better option than short term bonds:

“If it is a 50-50 chance as to the future general level of interest rates and the yield curve is substantially positive, then the odds are better in buying long term non-callable bonds than shorter term ones. This reflects my current conclusion and, therefore, I intend to buy bonds within the ten to twenty-five year range. If you have any preferences within that range, we will try to select bonds reflecting such preferences, but if you are interested in shorter term bonds, we will not be able to help you as we are not searching out bonds in this area.”

Of course, Mr. Buffett was well aware of the possibility of unpleasant scenarios facing the buyer of a twenty year bond, noting that quotational volatility could be significant although owners of such a bond would receive the contracted rate of interest if held to maturity, at least in nominal terms:

“Before you decide to buy a twenty year bond, go back and read the paragraph showing how prices change based upon changes in interest rates. Of course, if you hold the bond straight through, you are going to get the contracted rate of interest, but if you sell earlier, you are going to be subject to the mathematical forces described in that paragraph, for better or for worse. Bond prices also change because of changes in quality over the years but, in the tax-free area, this has tended to be - and probably will continue to be - a relatively minor factor compared to the impact of changes in the general structure of interest rates.”

With full knowledge of the past fifty-three years, it is cringeworthy to consider the difference between the financial results of those who invested in long-term bonds in 1970 versus those who held onto their shares of Berkshire Hathaway and Diversified Retailing.5 But of course, partners varied in their personal circumstances and time horizon. Still, despite setting expectations at a very low level, Warren Buffett clearly anticipated much better results from Berkshire Hathaway and Diversified Retailing based on comments made in his December 5, 1969 letter to partners:

“My personal opinion is that the intrinsic value of DRC and B-H will grow substantially over the years. While no one knows the future, I would be disappointed if such growth wasn't at a rate of approximately 10% per annum. Market prices for stocks fluctuate at great amplitudes around intrinsic value but, over the long term, intrinsic value is virtually always reflected at some point in market price. Thus, I think both securities should be very decent long-term holdings and I am happy to have a substantial portion of my net worth invested in them. You should be unconcerned about short-term price action when you own the securities directly, just as you were unconcerned when you owned them indirectly through BPL. I think about them as businesses, not ‘stocks’, and if the business does all right over the long term, so will the stock.”

In response to a question from partners regarding whether to hold shares of Berkshire Hathaway and Diversified Retailing, Mr. Buffett responded as follows in a December 26, 1969 letter to his partners:

“I can’t give you the answer on this one. All I can say is that I’m going to do so and I plan to buy more. I am very happy to have a material portion of my net worth invested in these companies on a long term basis. Obviously, I think they will be worth significantly more money five or ten years hence. Compared to most stocks, I think there is a low risk of loss. I hope their price patterns follow a rather moderate range related to business results rather than behaving in a volatile manner related to speculative enthusiasm or depression. Obviously, I cannot control the latter phenomena, but there is no intent to ‘promote’ the stocks a la much of the distasteful general financial market activity of recent years.”

In retrospect, obviously partners who were in a position to hold the shares for a long period of time would have been far better off doing so!

But we should also remember that Berkshire Hathaway, along with the overall market, was pummeled in the bear market of 1973-74 and partners with income needs might have been forced to sell at the very worst time. By providing advice on investing in bonds, Warren Buffett was trying to do the right thing for partners who might otherwise have been led astray. His advice on bonds was sound given what was known at the time and the fact that many partners required income producing investments.

Conclusion

As Warren Buffett wound down the Buffett Partnership after fourteen years of spectacular results, he obviously felt a responsibility to guide his partners as they faced the need to invest their share of the proceeds. His statements in the final letters to partners clearly expressed confidence in the shares of Berkshire Hathaway and Diversified Retailing that partners would receive. However, partners would receive the majority of their proceeds in cash which would need to be invested. For those with income needs, Mr. Buffett’s discourse on bond investing provided solid guidance.

It’s hard to fault Mr. Buffett’s discussion of bonds even given full knowledge of the inflation that took hold in the early 1970s and, after a brief respite, accelerated to record-high levels at the start of the 1980s. He did not have to provide this guidance at all, and given what he knew at the time, investing in tax-free bonds yielding 6.5% appeared to offer a reasonable risk/reward proposition. A tough pill to swallow is unpleasant but falls short of choking to death — in other words, partners with income needs taking this advice would have certainly suffered but they still survived.

In part two of this series, which I plan to publish later this week, I will turn my attention to the Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letters to see how Mr. Buffett’s views on inflation evolved during the 1970s and early 1980s.

Further Reading

Readers who are interested in learning more about the Buffett Partnership years might be interested in my review of Ground Rules, a book on the partnership written by Jeremy C. Miller which was published in 2016. I highly recommend the book.

If you found this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider referring a friend to The Rational Walk.

Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

This is taken from Warren Buffett’s letter to partners dated December 5, 1969. When the Buffett Partnership was dissolved, approximately 70% of capital was distributed in the form of cash that partners would have to reinvest on their own. The partnership distributed Berkshire Hathaway and Diversified Retailing stock to partners, some of whom chose to sell those shares and had additional cash to invest. Out of a desire to assist partners who wished to purchase bonds with their cash proceeds from the partnership, Warren Buffett wrote a final letter to partners dated February 25, 1970 containing a “very elementary education regarding tax-exempt bonds with emphasis on the types and maturities of bonds which we expect to help partners in purchasing next month.” As of September 18, 2023, all of the Buffett Partnership letters are available in a large PDF file published by the Ivey Business School at https://www.ivey.uwo.ca/media/2975913/buffett-partnership-letters.pdf.

I attempted to explain the risk of investing in bonds a few months ago since this seems to be a perennial source of confusion for investors, especially in recent months as interest rates rose to levels not seen in many years.

According to the calculator, $100,000 in March 1970 had the same purchasing power as $336,911 in March 1990, an implied compound rate of 6.26%.

The first factor, discussed in the prior paragraph was the shape of the yield curve. At the time of his letter, “a top grade bond being offered now might have a yield of 4.75% if it came due in six or nine months, 5.00% in two years, 5.25% in five years, 5.50% in ten years and 6.25% in twenty years.” This means that investors who elected to opt for a shorter term maturity than Mr. Buffett’s recommended range of 10-25 years would have suffered a penalty in terms of current income in exchange for less interest rate risk. These passages can be found on page 149 of the Ivey School compilation of letters linked to in Note 1 above.

Although it was a long and winding road, Diversified Retailing was eventually merged into Berkshire Hathaway on December 30, 1978, as discussed in the 1978 letter to shareholders.

It is interesting to compare Mr. Buffett's thoughts in these letters and his later thoughts in his letter to Katherine Graham (1975) on pensions. And then, to see how Brk is laid out today. As you said, he was trying to advise a variety of people in the BPL letters but it appears from the letter to Graham that for long term investors, stocks of good business's were the way to go. That and a healthy dose of cash (or cash like holdings) were the preferred layout. When the Washington Post was sold a few years ago, the pension fund was overfunded. Significantly over funded.