Time marches on relentlessly.

From birth to death of a human being, or any living creature, the passage of time is a constant rhythm, never ceasing to make forward progress. Try as we might to slow the relentless tick of the clock, Father Time remains undefeated.

Modern medicine can put a human being into a medically induced coma in order to better treat an underlying disease but time still marches on relentlessly with consequences such as loss of muscle mass, which gets more severe the longer the coma lasts. You can temporarily pause consciousness but not the relentless effect of time on the body.

When it comes to a civilization, there isn’t even such a thing as a medically induced coma. The world marches on and the individual actors in the drama experience the world day by day. Attempting to temporarily halt a complex human system risks the societal equivalent of muscular atrophy, both in terms of real productive capacity as well as the morale and underlying psychology of the people within the society.

Father Time remains undefeated, as he always has been and always will be.

The United States and much of the world is in the midst of a disruption that will no doubt be regarded as one of the most significant events of the twenty-first century. From our vantage point in early April 2020, we do not yet know how the coronavirus pandemic itself will turn out or what the economic and social ramifications will be, but it is already clear that we are living through a period of historic significance.

Coronavirus, or COVID-19, is not unique in terms of its severity or the fact that it exists and spread widely. The world has seen worse pandemics in the course of human history, with the influenza pandemic of 1918 being the most recent comparable example.1 However, the current coronavirus pandemic is unique in at least three important ways that are worth highlighting.

First, modern transportation systems allowed the virus to spread rapidly over vast distances. The length of time between infection and the appearance of symptoms is lengthy enough to allow apparently healthy people to move all over the world before health problems are even noted. Additionally, the presence of asymptomatic carriers who never show any symptoms facilitated greater spread compared to an epidemic such as Ebola which quickly strikes down its victims. In 1918, a human being could travel several hundred miles over a twenty-four hour period. In 2020, one can travel to nearly any corner of the world in that time. This has dramatic ramifications.

Second, once the extent of the problem could no longer be denied, forceful measures were taken to attempt to reduce transmission of the disease even at tremendous economic cost. Never before have so many countries voluntarily shut down vast portions of their economies in order to save lives. This is even more remarkable in light of the mortality risk being skewed toward the elderly who, from a cold-blooded economic perspective, have fewer “life-years” ahead of them than the young. Society was too slow to react but eventually made an honorable and moral choice to protect our parents and grandparents from harm, even at the cost of massive disruption.

Third, this is the first worldwide pandemic where the suffering and drama has been recorded in real-time for everyone to see, not only on television but on social media. The 1918 influenza pandemic left us with photographs and personal accounts of its victims, the medical community, and political leaders, but we do not have video footage of the crisis. Since the generation that witnessed the 1918 pandemic is almost entirely gone, we do not have living eyewitness accounts to turn to either. In contrast, we are witnessing, in real-time, the suffering of the coronavirus pandemic, and we can track the ever growing number of cases, deaths, and hospitalizations several times a day if we choose to.

John Maynard Keynes, writing during the Great Depression, coined the term “animal spirits” to describe the underlying aspects of human psychology that drive economic decision making and cannot be reduced to calculations on a spreadsheet. Keynes understood that an individual’s decision to do something depended on a certain level of confidence in the future, and that the level of confidence is informed by experience drawn from the past:

“Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits – a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.”

THE GENERAL THEORY OF EMPLOYMENT, INTEREST, AND MONEY, J.M. KEYNES, 1936

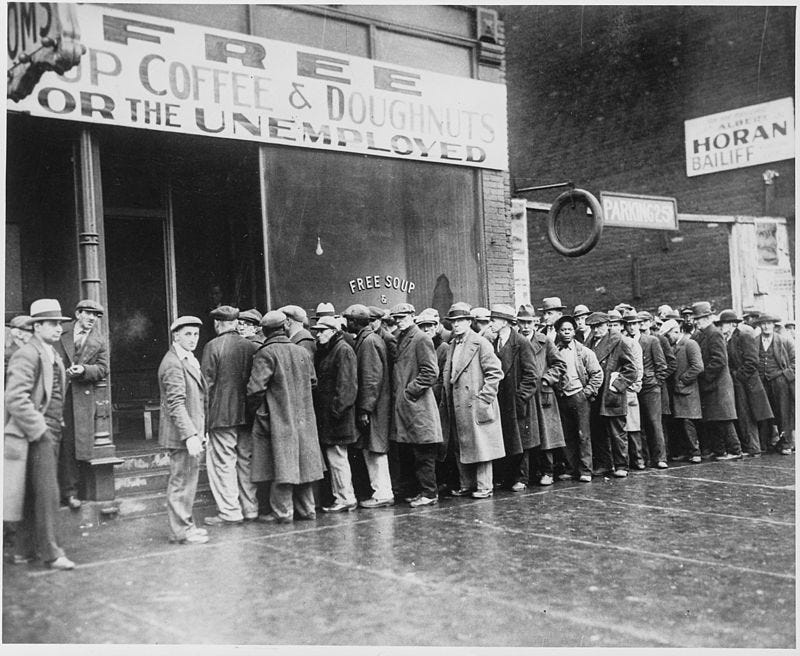

Human beings are not bloodless value-maximizing algorithms, but flawed and emotional beings who rely on qualitative as well as quantitative analysis when it comes to economic decision making. Those of us who have known older relatives who lived through the Great Depression or the World War II years might recall a sense of frugality and risk aversion that could seem excessively pessimistic at times.

This generation saw hardship and the darker side of life and that influenced their outlook well into the post-war years. Shaped by the Depression and tested by the war, this generation prudently and relentlessly built the post-war economy, igniting a quarter-century economic boom often referred to as America’s “golden age”.2 This generation, and the baby-boomer generation that followed, are now the most vulnerable to the current pandemic, and the ones we seek to protect with the forceful measures being taken to slow the rate of infection and avoid overwhelming our medical system.

The United States is clearly in the midst of a recession far more severe than the “Great Recession” that coincided with the 2008-09 financial crisis. There is no point in citing statistics at this point because estimates of GDP contraction are all over the place, but it is clear that major segments of the economy have all but shut down in recent weeks and remain shut down as we begin the second quarter. Unemployment will skyrocket from the multi-year lows recorded earlier this year and will most likely hit record levels not seen even during the Great Depression. This paragraph is necessarily qualitative; the tyranny of the false precision of “estimates” from economists, which are nothing more than guesses at this point, serve no useful purpose. Suffice it to say that conditions are bad, and likely to get worse in the short run.

There are major differences between the modern economy of 2020 and the economy of the Great Depression years. Those of us who are able to work from home are extremely fortunate and would not have this opportunity without the communication revolution brought about by the internet. Those who work in the restaurant and tourism industries are not nearly as fortunate, nor are those who work in the gig economy. The recent $2+ trillion federal spending bill will lessen the impact of this shock with one-time payments to individuals and expansion of unemployment benefits, but these are palliative measures. The same is true for the steps to shore up small businesses. Such steps, while needed in the short run, are the economic equivalent of trying to put the affected sectors of the economy into a medically induced coma.

In a complex system such as the modern economy, there are follow-on effects when major sectors simply shut down. All businesses face fixed costs which continue to be incurred even when revenue falls to zero. The most obvious include expenses such as rent and debt service. A distressed business that cannot pay such expenses will cause ripple effects when its suppliers and creditors face potential cash shortfalls of their own. Like a malign chain reaction, such ripples course over the entire economy like the ripples in a pond emanating from a thrown stone. No one knows the extent of the damage at this point.

The speed and shape of the recovery is on everyone’s minds at this point, and much will depend on Keynes’s animal spirits. Will the boarded up businesses scattered through countless American cities open up again when governments give the all-clear to do so? Will the customers of these businesses be willing to again go out and spend money in person after weeks or months of self-isolation?

Much will depend on whether the coronavirus pandemic is viewed as a one-time event or as a potentially recurring feature of our lives going forward. If the pandemic is viewed as a horrible, but temporary, interlude in an era of prosperity, then the government’s efforts to induce a “medical coma” of the hardest hit sectors of the economy could well succeed. Sound businesses will emerge with muscle atrophy. Those that were weak even before the crisis may never reopen at all. But the overall system will rebound and regroup.

Consumers, after enduring months of isolation, are likely to return to communal experiences sooner rather than later, as long as they believe that the risks of doing so are contained. Humans are highly social beings and not meant to live in isolation. There will be pent up demand and a sense of excitement to be able to resume our normal lives. A certain segment of the population, whether due to lingering risks for susceptible populations or general fear, might hold back but eventually most everyone will be lured back to restaurants, bars, performances and sporting events. Life will resume. The economy will come out of the “coma”, weakened but still very much alive, and slowly rebuild. We might get the much discussed “V-shaped” recovery and perhaps the economy will reach or exceed 2019 levels of output by 2021.

The alternate scenario is terribly grim. Businesses and consumers will start to view pandemics as a feature of twenty-first century life and will retrench. This is likely to occur if the economy reopens prematurely and is forced to shut down again in the fall if a second wave of infections gains traction. The initial euphoria of getting back to normal life will be crushed if there is a second round of shutdowns. Hopes of a “V-shaped” recovery will evaporate and we will likely enter years of economic stagnation, mired in depression.

Whether the current shutdown lasts another month or another two months is certainly of critical importance when it comes to estimates of second quarter 2020 GDP, which is what economists seem to be focusing on. However, the more important goal at this point is to ensure that the pandemic is contained to the point where it is unlikely to resurface again and require a second shutdown.

How will we know when it is safe to reopen without risking a ruinous second shutdown? Policy makers will have to balance risk of a second wave of infection with the risk of an extended shutdown. The emergence of a safe and effective therapeutic drug that could be used to save lives would be a major milestone. Testing a much larger percentage of the population would also be a step in the right direction. Experts believe that a vaccine could take twelve to eighteen months to develop. The Gates Foundation recently announced a major initiative to speed research into a vaccine. The current shut-downs clearly cannot continue for that long without risking that the patient never wakes up from the coma.

The next few weeks and months could very well set the direction for the next decade or even longer. Policymakers should focus on the science behind the pandemic and only reopen the economy when trusted experts believe that the risk of an uncontrolled second wave is well contained. A second wave of closures and shut-downs must be avoided at all costs. Such an event will likely kill animal spirits and bring about a depression.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

The Great Influenza by John M. Barry provides a compelling account of the 1918 pandemic.

This Wikipedia article provides some good information on the post-war boom, along with links to additional information.