Few would disagree with the proposition that reading is an important endeavor worthy of a serious investment of time and effort. However, this admission is usually followed by a lament about time constraints and the futility of embarking upon a journey that will take significant effort to complete. This objection is raised for contemporary books. It is raised even more forcefully when it comes to classics.

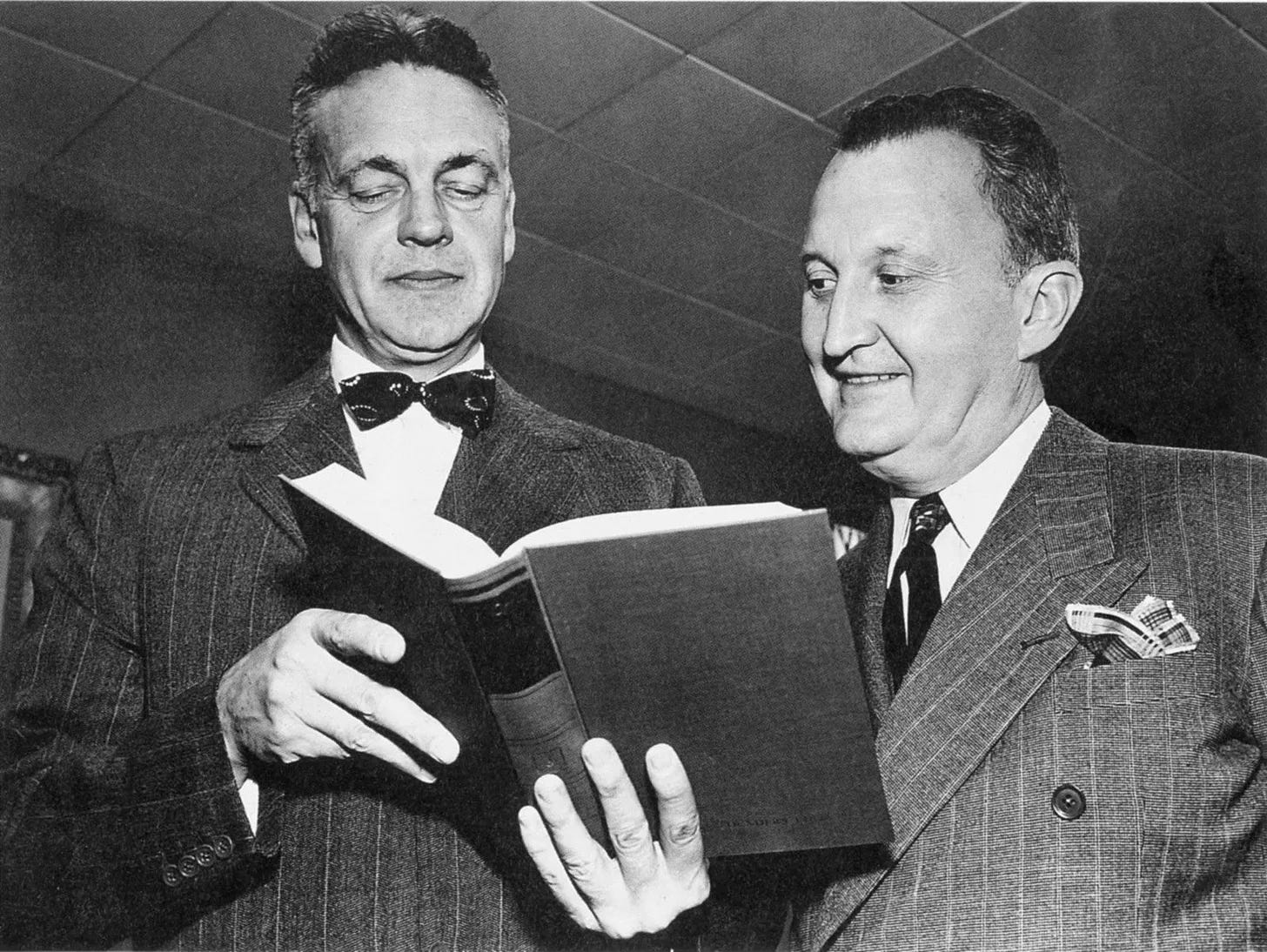

Robert M. Hutchins, one of the leading educational philosophers of the twentieth century, would find this attitude very frustrating. In his view, the increasing material abundance of American society held out the promise of providing a large number of people with sufficient leisure time to pursue a serious program of lifelong learning using the great gooks of the western world as the foundation. No longer would the classics be restricted to a privileged aristocracy, but would be accessible to all.

In The Great Conversation: The Substance of a Liberal Education, Hutchins makes a forceful case for pursuing the great books throughout life. In his view, education was not something that children and young adults should aim to merely plod through before entering the “real world.” Education should be pursued throughout life because the human experiences we encounter as we mature naturally lead us to see new things in texts that we have read in the past. For example, it is obvious that a sixteen year old reading Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina will have less of an appreciation for the message than a forty year old who has experienced marriage and children.

The Great Conversation is the first of fifty-four volumes contained within Great Books of the Western World which was originally published in 1952. The purpose of the first volume is to act as an introduction for the set, to explain why the works were selected, and to give the reader approaches for taking on an ambitious course of study. However, Hutchins does more than provide navigational instructions in The Great Conversation. He explains western traditions, the decline of a liberal education during the first half of the twentieth century, and makes the case for its resurgence as the world faced an existential threat during the early years of the Cold War.1

Hutchins believed that American democracy was at risk if citizens do not return to the roots of our civilization which serves as armor against the scourge of propaganda:

“We believe that the reduction of the citizen to an object of propaganda, private and public, is one of the greatest dangers to democracy. A prevalent notion is that the great mass of the people cannot understand and cannot form an independent judgment upon any matter; they cannot be educated, in the sense of developing their intellectual powers, but they can be bamboozled. The reiteration of slogans, the distortion of the news, the great storm of propaganda that beats upon the citizen twenty-four hours a day all his life long mean either that democracy must fall a prey to the oddest and most persistent propagandists or that the people must save themselves by strengthening their minds so that they can appraise the issues for themselves.”

Imagine what Hutchins, who died in 1977, would think about America in the early twenty-first century, in our age of social media and the idiocy that passes for our political discourse. If his concerns about propaganda and the threat of ignorance to democracy was plausible in 1952, it is a blaring five alarm fire in 2023.

Never before has more information been available as widely as in our time. I am old enough to remember when the internet was supposed to revolutionize education and lead to a new age of enlightenment by putting all of the accumulated wisdom of civilization at everyone’s fingertips. To say that it hasn’t quite turned out that way is perhaps the understatement of the century. Instead of delving deeply into worldly wisdom, large segments of our population have lost the ability to pay attention to any “content” that is longer than a TikTok video.

Hutchins never claims that reading the great books represents a panacea for all of society’s problems, but he clearly believed that the foundation they provide is critical for a fully enfranchised citizenry. He hoped that industrialization would provide the leisure time required for great books to reach the masses, and he believed that these books were not above the level of comprehension of the average person. For self-government to work, the citizenry must have an adequate understanding of their civilization so they can make intelligent choices. The elitist view, in his opinion, was to restrict the great books to those in academia and to an aristocracy that would be charged with making decisions for the majority.

“To put an end to the spirit of inquiry that has characterized the West it is not necessary to burn the books. All we have to do is to leave them unread for a few generations. On the other hand, the revival of interest in these books from time to time throughout history has provided the West with a new drive and creativeness. Great books have salvaged, preserved, and transmitted the tradition on many occasions similar to our own.”

Perhaps this was true in 1952 but is it still true over seven decades later? Or has our society become so far removed from the heritage of Western civilization to be beyond hope of repair? We cannot know how Hutchins would answer this question, but that might be beside the point. We represent the living and it is up to us to determine whether it makes sense to return to the great books or not.

The great books provide us with a multi-disciplinary education and protect us from the over-specialization that often plagues academia:

“The liberally educated man understands, by understanding the distinctions and interrelations of the basic fields of subject matter, the differences and connections between poetry and history, science and philosophy, theoretical and practical science; he understands that the same methods cannot be applied in all these fields; he knows the methods appropriate to each.”

Hutchins does not deny the need for specialization in certain contexts, but he believes that the foundation should be the great books. Armed with a multi-disciplinary mindset, one is then equipped to delve into specific fields of study and specialize. He does not restrict this to academics or professionals. All citizens, even those doing manual labor, should have in their minds the mental models contained within the great books, because one cannot discharge the duties of citizenship without it.

“The liberally educated man has a mind that can operate well in all fields. He may be a specialist in one field. But he can understand anything important that is said in any field and can see and use the light that it sheds upon his own.”

But do we have the time to pursue this course of study? Hutchins would be utterly baffled by claims that we do not.

“The degree of leisure now enjoyed by the whole American people is such as to open liberal education to all adults if they knew where to find it. The industrial worker now has twenty hours of free time a week that his grandfather did not have.”

From the standpoint of 1952, Hutchins is comparing the forty hour week of the typical industrial worker with the sixty-plus hour week that was common prior to the turn of the twentieth century. At the time he wrote, he must have known about television but obviously did not foresee that it would consume as much time for the average American as it did in the coming decades. Most people grew satisfied to passively receive entertainment rather than to devote their leisure hours to reading.

In today’s society, it has become rare for people to sit down in front of the television to watch shows at particular times, but streaming services provide us with even more content and even more flexibility in terms of when we can consume entertainment. Of course, the internet adds even more options to consume our time, much of it in a mindless near-hypnotic state. When we are not at home, we are glued to our smartphone screens constantly. If you doubt this, leave your phone at home, go to a nearby cafe, and watch what people around you are doing.

Far from being a stuffy snob, Hutchins comes across as a man with an idealistic notion of enlightenment for all. He hoped that his efforts as editor of the Great Books of the Western World would make reading accessible to all. He explicitly stated that he did not want the set to become “furniture” but to be consumed, not just once but constantly, again and again, as readers go through life.

“Great books are great teachers; they are showing us every day what ordinary people are capable of. These books came out of ignorant, inquiring humanity. They are usually the first announcements of success in learning. Most of them were written for, and addressed to, ordinary people. If many great books seem unreadable and unintelligible to the most learned as well as to the dullest, it may be because we have not for a long time learned to read by reading them. Great books teach people not only how to read them, but also how to read all other books.”

Hutchins forcefully promoted “interminable liberal education” and states that education through the great books is the obligation of every citizen. It is also good for our character and self-esteem.

“A man must use his mind; he must feel that he is doing something that will develop his highest powers and contribute to the development of his fellow men, or he will cease to be a man.”

We must decide for ourselves whether reading the great books is a worthwhile use of our time in the early twenty-first century. I believe that it is not only worthwhile but essential. While Hutchins had a somewhat utopian view of the reach of the great books, he was directionally correct in that far more people should be reading them. The vast majority will never touch these books but perhaps they will again be read outside of academia by ordinary citizens.

It is interesting to consider whether reading the great books using this particular fifty-four volume set makes sense today. Unfortunately, it has been out of print for decades and it is necessary to find used copies. The copy of The Great Conversation that I purchased was in good condition, but buying used books is a hit-or-miss proposition. I am not new to the great books and already own copies of several titles. However, I am planning to look for a complete set of Great Books of the Western World.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

For our purposes, and for Hutchins, the term “liberal education” is meant in its classical sense in terms of the values of the enlightenment in particular and western civilization in general, not as the word “liberal” is used in contemporary American politics. Also note that while Hutchins refers to “men” in his writing, we should take this to mean all people. I am sure that this is what he meant given his views of the universality of the great books.