“Public affairs go on pretty much as usual, perpetual chicanery and rather more personal abuse than there used to be.”

— John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, April 17, 1826 1

Financial Scandals and Bailouts in the 1790s

What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.

— Ecclesiastes 1:9

Political intrigue, allegations of financial impropriety, vicious attacks in the media, intemperate politicians, and anonymous trolling. These are all obvious characteristics of political life in America two decades into the twenty-first century and many observers bemoan the abandonment of more collegial days earlier in our history. It is part of our nature to idealize the way things used to be and, in the process, we are prone to forgetting that people who lived long ago were also subject to the realities of the human condition. As we celebrate Independence Day, it is interesting to take a look back at a period of history shortly after our founding when partisan politics was in its infancy and the stakes couldn’t have been higher for the opposing camps.

Despite George Washington’s efforts to forestall the development of partisanship, by 1792 his own administration was split into two camps, with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton most forcefully representing the cause of the Federalists, who supported a more vigorous executive within a powerful national government, and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson who was the champion of republicanism that sought to limit the centralizing tendencies of the Federalists. The broad strokes of this long-running dispute might be well known to those with a passing understanding of American history, but only those who have delved into the background in some depth can fully understand the vicious animosity and partisanship that easily rivals what we have experienced in modern times.

On February 25, 1791, President Washington signed the legislation establishing the first Bank of the United States. The establishment of the bank was an expansion of the power of the federal government supported by Alexander Hamilton and vigorously opposed by Thomas Jefferson and his allies who viewed the bank as an unconstitutional measure designed to benefit the business and investing community at the expense of the general population. One of the measures of the legislation was to establish a sinking fund that was designed to begin paying off the national debt, which had been expanded in 1790 at Hamilton’s urging when the debt of states was assumed by the federal government. Jefferson was named as one of the commissioners of the sinking fund.

Only one year after the bank was established, a credit crisis known as the Panic of 1792 was caused by speculation on the part of prominent bankers including William Duer, who was a friend of Alexander Hamilton and previously served as the first Assistant Secretary of the Treasury. Duer and other speculators came up with a scheme to use large loans to corner the government debt market. United States debt securities were needed by those who had invested in the initial public offering of the Bank of the United States because the terms of the offering required them to pay for their stock in installments comprised of 25 percent specie and 75 percent government bonds. Gaining control of the government bond market meant that Duer and his partners could potentially reap a windfall due to the presence of forced buyers who needed to settle their installment payments.

The collapse of the scheme in February and March 1792 caused Hamilton to take measures to prevent a broader credit crisis. He utilized the sinking fund that was established along with the Bank of the United States to purchase government securities which had the effect of propping up prices and forestalling a broader crisis. However, the political fallout from doing so was severe and the acrimony easily rivals controversies we have seen in modern times. The crux of the dispute was whether Hamilton had authority to utilize the sinking fund as he did, and especially whether he was justified in purchasing securities at par when they were trading below par in the depressed market during the panic.

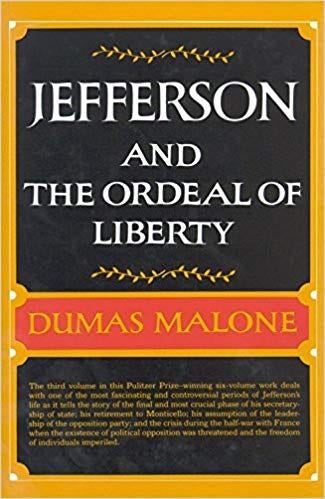

Dumas Malone covers this episode in Volume 3 of his six volume biography of Thomas Jefferson which was published in 1962. Malone frames this dispute in the context of the long running acrimony between Hamilton’s Federalist faction and their opponents led by Jefferson, along with James Madison and others in Congress. The extent to which Jefferson himself led the charge to investigate Hamilton’s conduct has long been in dispute. Malone acknowledges that Jefferson was in communication with the members of Congress who launched the investigation but minimizes the extent of a larger conspiracy. During this period, Hamilton was far more vocal in what he was willing to say personally while Jefferson tended to operate more via surrogates. Much of this had to do with the personalities of the men, but the personal nature of the dispute is not in question.

One of Jefferson’s allies in the House of Representatives was thirty year old William Branch Giles, a fellow Virginian who was also close to James Madison. The resolutions that were introduced to investigate Hamilton’s conduct were known as the Giles Resolutions. Malone explains the crux of the charge against Hamilton in this extended excerpt: 2

“Specifically, the question related to the price at which government securities might be bought in this process of debt reduction, and it was answered in Hamilton’s favor by the voice of the Chief Justice, who held that under the act they might be purchased at more than the market price, up to par value. The point is that Hamilton wanted to buy at par at that time, when securities were below par on the market. His major purpose, as he claimed, was to maintain the credit of the government, but numerous speculators, including his friend the notorious William Duer, had been caught in the sharp decline of securities. Hamilton wanted to stay the panic, but to the mind of Jefferson he was purposely supporting the speculators. Furthermore, Jefferson believed that the purpose of the Sinking Fund was to retire the debt — as much of it as possible and under the most favorable conditions. He may not have sufficiently appreciated the positive functions of the Treasury in maintaining the level of public securities, but his simple philosophy was one that unsophisticated citizens could readily understand. Like him, they could not see why the government should pay more for its own securities than it had to, for the apparent advantage of men like Duer.”

The Giles Resolutions were debated in the House of Representatives, but all failed to win a majority which represented a resounding victory for Hamilton and his Federalist cause. Jefferson, always reserved in his public statements, was willing to be a little more open in a private letter to his son-in-law following the vote:

“Others contemplating the character of the present house, one third of which is understood to be made up of bank directors & stock jobbers who would be voting on the case of their chief: and another third of persons blindly devoted to that party, of persons not comprehending the papers, or persons comprehending them but too indulgent to pass a vote of censure, foresaw that the resolutions would be negatived by a majority of two to one. Still they thought that the negative of palpable truth would be of service, as it would let the public see how desperate & abandoned were in the hands in which their interests were placed.”

We can see from this private correspondence that Jefferson not only supported the resolutions, but that he knew that they would very likely fail but wanted the political point made that the Federalists were acting against the interests of the majority. He went on to explicitly characterize the “corrupt maneuvers of the heads of departments”, obviously in reference to Hamilton.

Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State at the end of 1793 and retired to Monticello to look after his long neglected farms and personal interests, but he never left the political scene in terms of his influence on his proteges who remained in government, and he was back in the political maelstrom in early 1797 when he took office as Vice President.

Our times could not be more different from the 1790s in myriad ways, with the most obvious being the speed of travel and the instant and nearly universal access to information. What has not changed is human nature, with all its political backstabbing, intrigues, and scandals. In 1790, people and information could not travel faster than a man on horseback could ride, and information was distributed on paper to those with the resources available to purchase it and who had the literacy necessary to understand it.

Today, politicians, journalists, and ordinary citizens can communicate instantly on platforms like Twitter and the velocity of information, and misinformation, is like nothing the world has ever seen before. It is interesting, and entertaining, to consider how the personalities of Hamilton, Jefferson, and others would have navigated the age of social media for their political benefit. It is easy to imagine Hamilton as a heavy user of long Twitter “threads”, while Jefferson might be more inclined to put out press releases or let surrogates go to battle on his behalf.

Financial crimes and outright greed are not new vices of our times, with financial bubbles, scandals and cronyism being as old as the nation itself. As an epilogue, however, we can return to the case of the notorious William Duer. Unlike the villains of the financial crisis of 2008-2009, most of whom have bounced back very nicely, Duer paid a very heavy price for his sins. He spent the rest of his life in a debtor’s prison and died in disgrace in 1799.

Recommended Reading

Jefferson and His Time, a biography of Thomas Jefferson by Dumas Malone

American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson by Joseph Ellis

Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation by Joseph Ellis

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both died on July 4, 1826, exactly fifty years after the Declaration of Independence. After the bitter election of 1800, they did not correspond with each other for over a decade. In 1812, they renewed their correspondence which continued until just months prior to their deaths. The letters are available on Founders Online for free as well as in a book edited by Lester J. Capon.

Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty, Chapter 2

Excellent piece. Thanks!

very interesting read