How to Lie With Statistics

Darrell Huff's humorous 1954 classic reveals how statistics can be used to mislead.

Social norms govern how individuals interact with each other and with society at large. Many norms have been incorporated into legal systems but most continue to be informal conventions. A significant percentage of the population will fail to adhere to established social norms despite the penalties that exist for those who fall out of line and are discovered. The worst offenders are those who, on the surface, appear to be exemplars of society but successfully flout our rules with impunity, often operating in subtle and nearly undetectable ways. Such serial offenders typically have charismatic attributes that mask underlying sociopathic tendencies.

Society cannot function at all in an environment where there is no trust, so we do not have the option of adopting a cynical attitude toward everyone and everything we encounter in day-to-day life. We cannot assume that everyone transacting with us is out to cheat us. We cannot form any meaningful relationships with others if we default to believing that they are acting disingenuously from the outset. At the same time, we have to take intelligent steps to avoid being the patsy at the poker table. We must find a way to willingly expose ourselves to a certain degree of vulnerability but, especially when the stakes are high, we would be ill advised to depart very far from the concept of “trust, but verify”.

Letting Your Guard Down

Fortunately, life does not have to be so grim. Most of time, in day to day life, we can behave in a manner that gives everyone the benefit of the doubt whether the interaction is commercial or personal in nature. We benefit from the mental shortcuts that flow from acting in a manner that assumes that others are behaving in keeping with our society’s social mores. The downside of occasionally being taken advantage of in small matters is outweighed by the many positive interactions and ease of living with a positive and trusting attitude. Life is more pleasant when we are not constantly on guard.

The time to adopt an attitude of informed skepticism is when the stakes are high. It should go without saying that consumers are well served to be on guard when making transactions such as purchasing a vehicle or buying a home. In fact, any time there is a major asymmetry of information and experience, it pays to be very skeptical regarding the motives and strategy of the person on the other side of the table. Understanding how those with malign intent attempt to deceive us can be invaluable when it comes to defending against such attempts.

How to Lie with Statistics holds the strange distinction of being a book about … statistics that is nevertheless very amusing and informative for the general reader. Written by Darrell Huff in 1954, the book somehow avoids getting bogged down in math. Huff instead resorts to clever illustrations and cartoons to make his points regarding the myriad ways in which statistics can be used to deceive.

The 1954 price and salary information he uses is unadjusted for inflation over the past sixty-five years, which only adds to the charm of the narrative.1 Huff is well aware that the techniques he discusses could become a “manual for swindlers” but notes that “the crooks already know these tricks; honest men must learn them in self-defense.” The tricks that Huff describes were fooling people back in the 1950s and the same techniques continue to work wonders today. It seems like little has changed in terms of lack of basic numeracy over the decades.

One of the most pernicious aspects of using statistics to mislead is that most people take mental shortcuts as soon as they see numerical figures in an article. When used in certain ways, statistics can serve as a sort of trump card for bad actors. Through manipulative choices, numbers can be developed to “prove” all sorts of disingenuous arguments.

Huff covers many of the straight forward fallacies that most of us are very familiar with, such as the confusion between the use of median and mean averages which can be particularly misleading when it comes to data sets that are not normally distributed, such as wealth in the United States. Of the methods described by Huff, two jump out as interesting enough to discuss at further length: The Semi-Attached Figure and The Gee-Whiz Graph.

“Compared to What?”

If you are selling something that has no proven benefits, or making an argument that has no intrinsic merit, not all is lost if you are willing to engage in a deceptive slight-of-hand that Huff refers to as the semi-attached figure:

If you can’t prove what you want to prove, demonstrate something else and pretend that they are the same thing. In the daze that follows the collision of statistics with the human mind, hardly anybody will notice the difference. The semi-attached figure is a device guaranteed to stand you in good stead. It always has.

HOW TO LIE WITH STATISTICS, P. 76

Let’s say that you are the marketing manager responsible for coming up with an ad copy for a product that isn’t demonstrably better than its competitors. Huff uses the example of a juice extractor. The marketing manager cannot come up with any data to show that the juice extractor is more efficient or easier to use than competing products, but it would be easy to prove that the juicer is much better than using an old fashioned hand reamer. There would be no explicit lie in the statement that the device “extracts 26 percent more juice as proved by laboratory tests”. The deception rests in the act of omission: compared to what?

A similar trick is common within the investment management industry. An investment manager with a mediocre track record can easily present misleading data that is technically true. For example, let’s say that an investor made a public call that happened to “bottom tick” a particular stock, or catch the exact point at which the stock stopped falling and started to rise. The investor can say something like “after I called the bottom on Company XYZ and purchased shares, the stock went up over 2000 percent over the next two years!” This might technically be true. But it doesn’t mean that the investor had the foresight to hold that stock for that stellar gain. He could very well have sold it after it went up just five or ten or fifty percent!

Chart Crime!

Although Huff does not use the term “chart crime” in the book, he does have a full chapter dedicated to the “Gee Whiz Graph”. The reason charts and graphs are used so frequently in the media and in sales presentation is because most people are very visual and numbers naturally “come to life” when put into a drawing. However, a chart can be technically true but still provide grossly misleading impressions. For example, presenting only a portion of a chart can make changes look more dramatic than they really are. If you are showing data that ranges between 16 and 18, the variations will look much more dramatic if the y-axis ranges from 15 to 20 than if the y-axis ranges from 0 to 100. Of course, in some cases, small variations are meaningful. If the data from 16 to 18 represents the range of a company’s net margin over a decade, a tighter y-axis will show meaningful variations over time. The designer of the graph has the responsibility to present the data in a way that is not only accurate but meaningful.

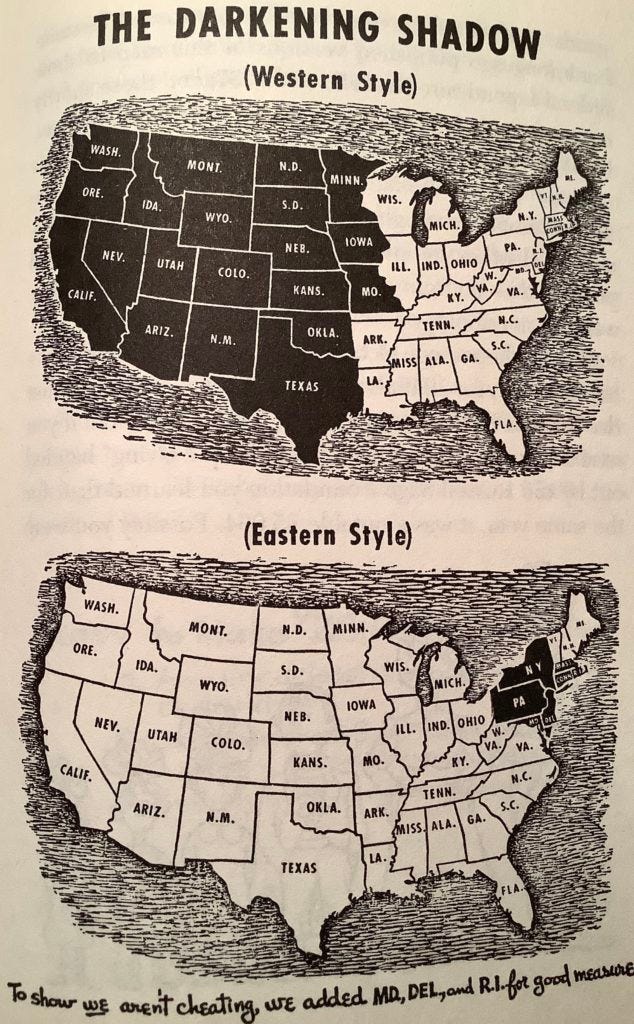

“Map crime” is closely related to chart crime. It involves using a map to represent data to suit a particular agenda. For example, say that you want to represent the share of national income collected by the government in the form of taxes. Huff shows two ways in which this could be represented on a map of the United States:

Both the western and eastern style maps show an accurate representation of federal spending that is equal to the total incomes of the people living in the shaded states. The large area shaded in the western style map is due to the fact that, in 1954, the western states had vastly smaller aggregate income compared to eastern states. The eastern map merely demonstrates that a few eastern states had very high income. While both maps are accurate, someone who wanted to present a threatening picture of big government would opt for the western map while his political opponent favoring a larger state would choose the eastern map.

A similar effect exists when one looks at the results of a presidential election based on geography rather than population. For example, the map below shows the results of the 2016 election by county. If you wanted to present the impression that nearly everyone in the country voted Republican, you could use this map even though the reality is that the majority of the population actually voted for the Democratic candidate. Using land area rather than population density presents a misleading image.

As Jason Zweig wrote in his review of the book, Huff provides invaluable guidance for readers who are trying to figure out if they are being manipulated through the clever use of statistics. For those of us who took statistics in college, there isn’t much of anything that is new from a mathematical perspective. However, the book serves well as an introduction for those who are not familiar with the subject and is also a great refresher for the rest of us.

Robert Cialdini’s classic book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion is one of Charlie Munger’s favorite books, and for many good reasons. Mr. Munger has long been focused on developing a better understanding of the psychology of human misjudgment. Human beings have developed many psychological tendencies over thousands of years and, normally, these tendencies serve as useful shortcuts that allow us to make quick and efficient decisions. However, in certain contexts, our instincts can lead us astray especially when we are being manipulated by experts.

Just as Huff did not intend his book on statistics to serve as a roadmap for deceit, Cialdini wrote his book not to empower corrupt behavior but to warn the public against falling into avoidable traps. By publicizing the methods that “compliance professionals” utilize, Cialdini does the general public a service by highlighting situations in which we should exercise informed skepticism.

Over a decade ago, I wrote a brief article applying Cialdini’s ideas to Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme.2 Madoff used the principles of social proof, authority, and scarcity to manipulate his clients for decades despite many warning signs. People who should have known better simply looked the other way. They were not sufficiently skeptical.

Uncomfortable Obligations

Reciprocity is one of the most powerful human tendencies and it has actually served us very well throughout human history. Without reciprocity, society would not function very well. Cialdini emphasizes the competitive advantages provided by the reciprocity rule:

Make no mistake, human societies derive a truly significant competitive advantage from the reciprocity rule, and consequently they make sure their members are trained to comply with and believe in it. Each of us has been taught to live up to the rule, and each of us knows about the social sanctions and derision applied to anyone who violates it. The labels we assign to such a person are loaded with negativity — moocher, ingrate, welsher. Because there is general distastes for those who take and make no effort to give in return, we will often go to great lengths to avoid being considered one of their number. It is to those lengths that we will often be taken and, in the process, be “taken” by individuals who stand to gain from our indebtedness.

INFLUENCE, P. 20

The almost universal instinct to reciprocate when someone does something that puts us in their debt allows compliance professionals to easily manipulate us. This can be fairly obvious, such as when we are presented with a “free gift” in a setting like a timeshare sales presentation, or when a local stock broker offers a “free lunch” to those who agree to listen to his presentation. The recipients naturally feel an obligation after receiving something of value. Many people will, in fact, reciprocate just to cancel out their obligation even if they do not want whatever is being sold.

Compliance professionals also exercise more subtle pressures that harness the reciprocation tendency. Cialdini points out that a concession in a negotiation normally creates a psychological need for the other party to also make a concession. This is why it is extremely dangerous to let anyone else control the terms of a negotiation. If a used car salesmen starts a negotiation from an inflated sticker price, he can make a fake initial “concession” that doesn’t come close to lowering the price to the car’s blue book value. The buyer can be manipulated into agreeing to pay more simply by the act of the salesman making a fake concession.

Skepticism, Not Cynicism

The risk we face when we learn about these psychological tendencies is to guard vigilantly against falling into traps even at the risk of flouting social conventions that are useful and bind people together in positive ways. When you are dealing with a used car salesman, informed skepticism and even cynicism might be warranted. It is probably a good idea to avoid accepting any “gift” from the salesman, even something as trivial as a free can of soda. Similarly, it is probably best to not allow a realtor to buy your lunch between visiting homes. That’s simply prudent.

But should you act with suspicion when you move into a new home and your neighbor brings over a casserole or a bottle of wine to welcome you to the neighborhood? It is true that by accepting you will likely feel a need to reciprocate in some way, but this is a healthy form of reciprocation. You’ll get to know your new neighbors as part of the process. It is possible that your neighbor may try to sell you life insurance the next time you see her, but it is more likely that she’s just being friendly. As Cialdini points out, we will always encounter people who are authentically generous. Refusing the kindness of all people, regardless of the context in which it occurs, will result in isolation.

Malcolm Gladwell’s latest book, Talking to Strangers, was all about the risk of miscommunication when we interact with people who we do not know well.3 We often make the mistake of thinking that other people are transparent when, in fact, we cannot really see into their minds. Giving people the benefit of the doubt and assuming benign intent is a good way to live our day to day lives, especially in cases where the stakes are low. However, when the stakes are high, defaulting to a skeptical outlook is only prudent. We must be vigilant regarding avoiding the traps that compliance professionals set out for us. At the same time, we should know when to let our guards down, even if only temporarily and in settings where a worst case outcome will not hurt us too badly.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Federal Reserve Chairman Powell might consider low inflation to be “one of the major challenges of our time“, but the nearly ten-fold increase in the price level since 1954 leads one to believe this challenge is “solvable”. The reader can just add a zero to the 1954 prices to approximate the effects of inflation.

The article on Madoff in February 2009 was actually the sixth article to appear on The Rational Walk.