Reading Plans

The Great Books cast a formidable shadow but most of them were meant to be read by a wide audience. Reading plans make it easier to get started.

The shipment arrived in four boxes and weighed in at over a hundred pounds. As I opened the first box and removed a book, the unmistakable scent of an old bookstore wafted into my living room. I carefully unpacked the books and inspected each of them. I was delighted to find that the vast majority of the books appeared to be in like-new condition even if they are between six and seven decades old. The larger ones had a certain intimidating heft to them, but all appeared worthy of respect.

It is tricky to acquire out-of-print books in good condition. Fortunately, one of my readers offered to sell his set of Great Books of the Western World. Since receiving the set a week ago, I have surveyed the contents and read its introductory material. I am not entirely new to the Great Books, but I have never attempted to read them in an organized manner. In this article, I’ll describe the books that I have acquired and how I will structure a reading plan requiring many years to complete.

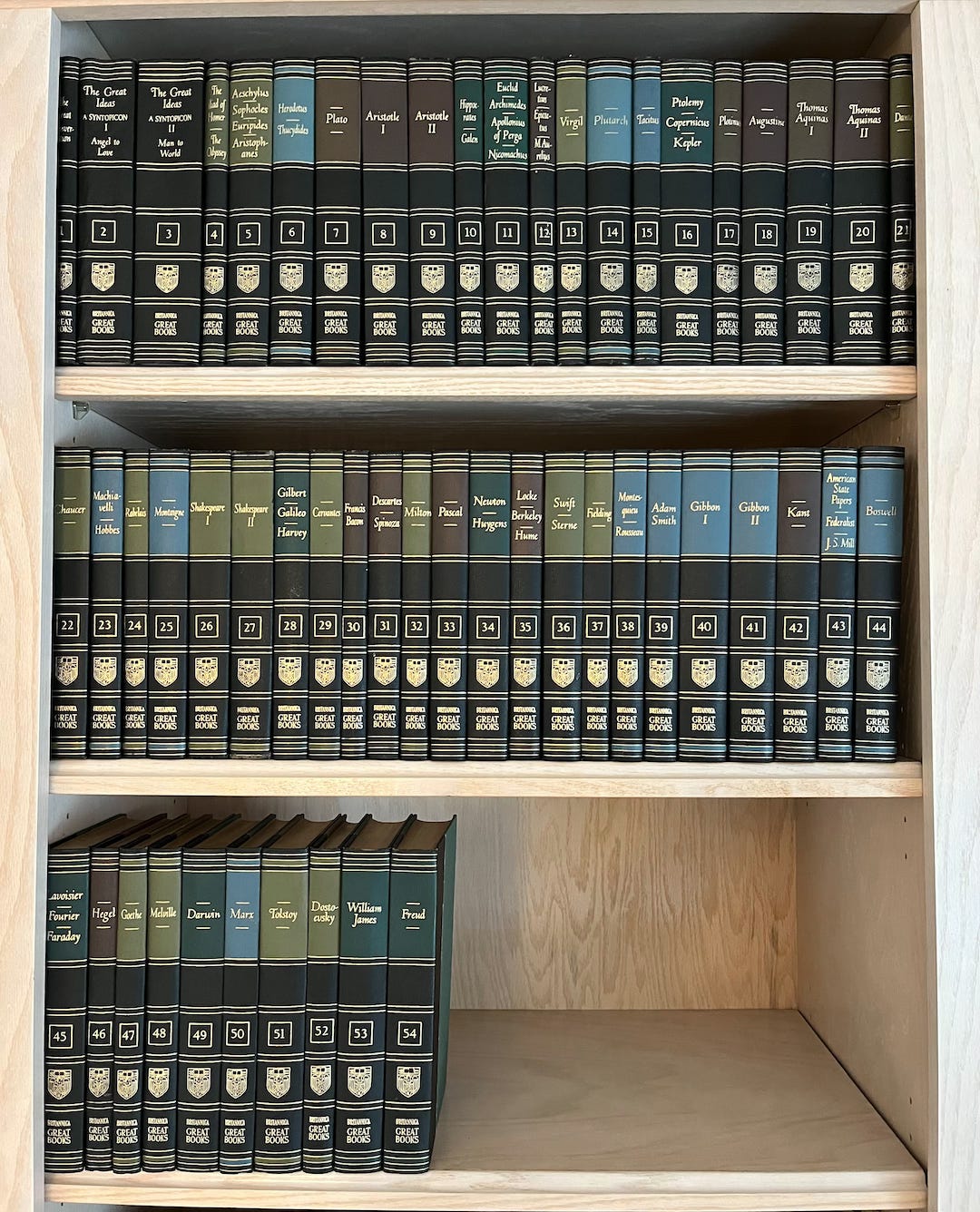

Great Books of the Western World

The heart of the collection is the fifty-four volume Great Books of the Western World which was published in 1952 by Encyclopedia Britannica. Last month, I separately purchased The Great Conversation, which is the first volume of the set, and I wrote an article with my initial impressions. A brief excerpt of my article appears below:

The Great Conversation is the first of fifty-four volumes contained within Great Books of the Western World which was originally published in 1952. The purpose of the first volume is to act as an introduction for the set, to explain why the works were selected, and to give the reader approaches for taking on an ambitious course of study. However, Robert M. Hutchins does more than provide navigational instructions in The Great Conversation. He explains western traditions, the decline of a liberal education during the first half of the twentieth century, and makes the case for its resurgence as the world faced an existential threat during the early years of the Cold War.

Many of our concerns today about an uninformed citizenry prone to propaganda were issues in the early 1950s as well. At that time, society had already moved beyond what Robert M. Hutchins regarded as the foundations of a liberal education and his goal was to bring back the Great Books, not just for the elite but for ordinary people. He insisted that the Great Books were written to be read by everyone but had somehow acquired a reputation for being formidable and inaccessible.

Most of us read a few of the Great Books in college but typically our reading of these works were not in reference to each other so we do not fully benefit from the “great conversation” between these brilliant thinkers who lived centuries apart. Even those who have read many of these works before can benefit from reading them again later in life. As Mr. Hutchins wrote, reading Macbeth at sixteen is an entirely different experience than reading it at thirty-five.

How were the books in this set selected?

“The criteria for choosing each book in this set were excellence of construction and composition, immediate intelligibility on the aesthetic level, increasing intelligibility with deeper reading and analysis, leading to maximum depth and maximum range of significance with more than one level of meaning and truth.”

Mr. Hutchins goes on to say that there are no prerequisites for picking up one of the books and just starting to read. We should not be intimidated by the authors, or what we have heard about them. In this way, he thought that readers who were never exposed to these works in school might actually have an easier time with the project since they have no preconceived notions about the difficulty of the task.

The Wikipedia entry for the set contains a full listing of the works that are found within it, so I will not list them here. But so the reader can know where I am coming from, I will list the works within the set that I have read in the past:

The Iliad and The Odyssey by Homer (several times, different translations)

The History of the Peloponnesian War (partially in college)

The Discourses by Epictetus

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius (several times)

Confessions by Saint Augustine (Books I-VIII, very recently)

Montaigne’s Essays (currently on a slow second reading)

Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith (partially in college)

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon

American State Papers (Declaration, Constitution, Federalist Papers)

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Given the publication of the set in the middle of the twentieth century and the desire of the editors to include books that stood the test of time, very little twentieth century literature is included. In addition, I was surprised to see that other works by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, which I have read, do not appear in the set. There is no doubt that hard choices had to be made regarding which authors and works to include.

The second and third volume comprise The Syntopicon. These two volumes serve a critical function. As the introduction explains, the Syntopicon contains over a hundred “great ideas”, each of which is covered in an essay. The essay covers the idea and explains how various works within the set relate to the idea and to each other. The function of the essay is to orient the reader who is interested in delving into a specific set of topics related to an idea. References are then provided to the Great Books themselves, providing the reader with nearly unlimited paths to take.

For example, if a reader is interested in democracy, he can turn to Chapter 16 of the Syntopicon and read an eight page introduction surveying the field. Following the essay, democracy is divided into seven topics and sub-topics. If I’m interested in the subtopic named “the training of citizens”, I am referred to works ranging from Euripides to Plato to Milton to Montesquieu to The Federalist Papers, among many others. In this way, we can see the “great conversation” about educating citizens over time, as these authors “discuss” the matter with each other and with us.

Robert Hutchins and Mortimer Adler believed that the Great Books speak for themselves and do not require much explanatory material. As a result, aside from brief biographical entries, there are no introductions within the set. Surveying some of the author introductions, I found them to be sufficient to get a general sense of the author’s background. Unsurprisingly, I found the biographical sketches more adequate for authors I have yet to read, such as Plato, than for authors who I know well, such as Montaigne and Marcus Aurelius.

How should the reader get started? The editors would have said that we should start anywhere we happen to have an interest but many readers, myself included, are looking for a more organized approach. This set includes a ten year reading plan comprised of eighteen selections per year but we are just given the titles, not the rationale behind them or any guidance for approaching each work.

The photo below shows my set of Great Books of the Western World.

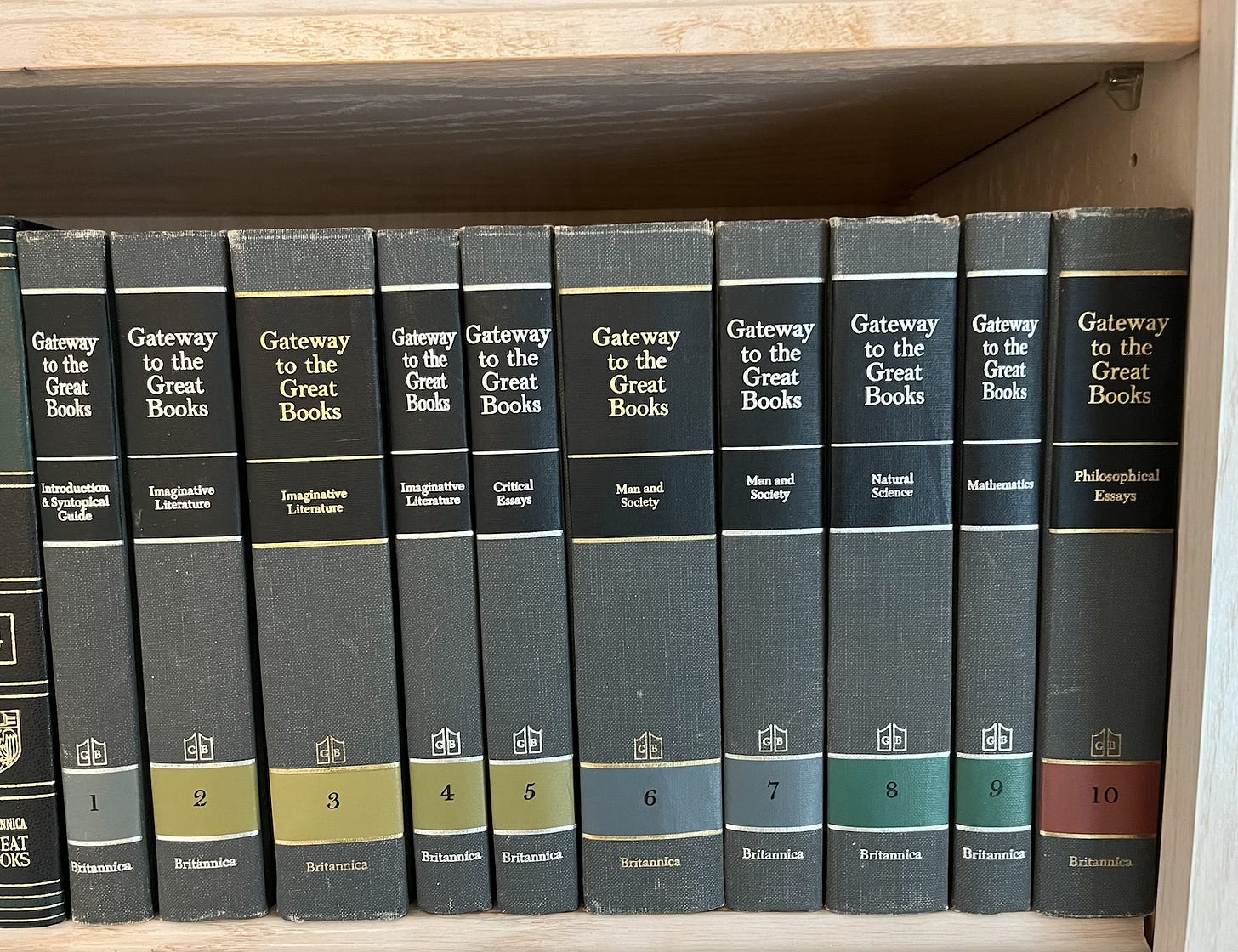

Gateway to the Great Books

In 1963, Gateway to the Great Books was published “to lead you on, to fortify you, to encourage you, to seduce you into the habit of reading, and in particular into the habit of reading Great Books of the Western World.” Robert Hutchins explains that the ten volume set is meant to serve as an “attractive, instructive, entertaining interlude or supplement” to those who are interested in the Great Books.

Like in The Great Conversation, the editors make a forceful case in the introduction for reading the classics and rail against the manner in which most people fritter away their free time on vapid “fun” that might be interesting in the short run but can get boring very quickly. “It is against nature for a man to devote himself to occupations little different from those which might be enjoyed by a pig, a pigeon, or even a whale.” I can only imagine what Mr. Hutchins would have thought of our pastimes in 2024.

Many of the authors that appear in Great Books of the Western World also appear in Gateway to the Great Books, but for the most part the Gateway selections are shorter and simpler for new readers to understand. A particular emphasis is to introduce younger readers to the Great Books and, for this purpose, a “plan of graded reading” is provided for students in 7th and 8th grades, 9th and 10th grades, 11th and 12th grades, and the first two years of college. Perhaps students were more advanced in the 1960s because it is hard to imagine today’s 7th graders reading many of these selections.

The Wikipedia entry for the set lists its full contents. Most of these selections are classics and some were “promoted” to the Great Books series when it was expanded to sixty volumes in 1990. I have read several of the selections in the Gateway series and can see the case for reading some of them before approaching works in the Great Books. For example, two of Leo Tolstoy’s shorter works are included in the Gateway. It would make good sense to read The Death of Ivan Ilyich before tackling War and Peace.

From a physical perspective, the Gateway set was in less pristine shape compared to the Great Books set but they are still in fine condition. The Great Books have fancier features, such as gilt edging, and seem weightier and more durable.

The photo below shows my set of Gateway to the Great Books:

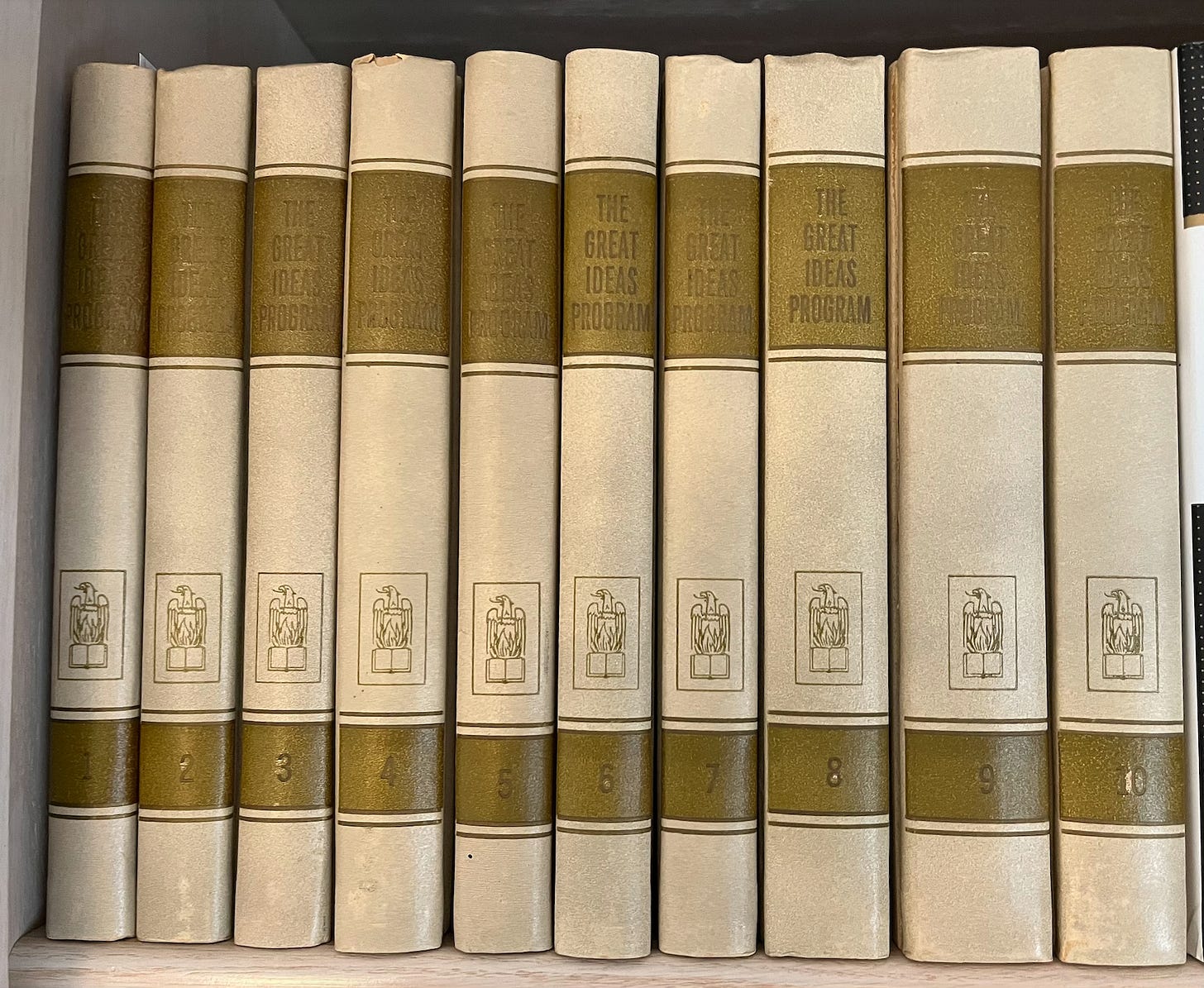

The Great Ideas Program

The Great Ideas Program is a ten volume companion to Great Books of the Western World. I had no background information on this set prior to receiving it but I am very glad to own it. This set was published between 1959 and 1963 due to demand for an organized program of reading that was lacking in the Great Books set itself.

Each volume in this set contains detailed reading plans for The Great Books.

Volume 1: An Introduction to The Great Books and a Liberal Education

Volume 2: The Development of Political Theory and Government

Volume 3: Foundations of Science and Mathematics

Volume 4: Religion and Theology

Volume 5: Philosophy of Law and Jurisprudence

Volume 6: Imaginative Literature I

Volume 7: Imaginative Literature II

Volume 8: Ethics — The Study of Moral Values

Volume 9: Biology, Psychology, and Medicine

Volume 10: Philosophy

The editors prepared this set “to provide a way into the Great Books for readers who would like help in their first reading of them.” Each volume contains fifteen readings that are designed to take a typical adult approximately two weeks to read, understand, and contemplate. Introductory material is provided for each reading and elements that might pose difficulties are highlighted. This material does not attempt to “spoon feed” the reader but does provide useful information to get started.

Yesterday, I took several hours to go through the first reading in Volume 1 (Plato’s Apology and Crito). Like many people, I am familiar with the trial of Socrates but if I ever read the Apology and Crito, it was in a long-forgotten caffeine fueled effort to check the box on a college assignment. Setting aside a few hours to really read these dialogues was a great experience. I plan on a second reading later this week.

Each reading is supposed to account for two weeks since the goal is not to speed read these selections but to really read them, perhaps more than once, and then to write about them using prompts that the editors provide.

The photo below shows my set of The Great Ideas Program:

My Reading Plan

I am not a college student and have the luxury of taking my time as I approach these sets. The goal is not to earn some credential or degree but to profit from a better understanding of Western Civilization, something my education failed to deliver.

One could start with the first volume of the Great Books and read each one in sequence but my gut feeling is that this is a good way to get bogged down and probably not the most satisfying way to proceed. A better option might be to read each of the 102 essays in The Syntopicon and to branch out from there based on my interests. I like the idea of reading these essays and plan to do so, but I am hoping for a more organized approach that will take me through a broad variety of the works.

For my purposes, the ten volumes of The Great Ideas Program seem tailor made. By following the fifteen readings contained within each of the ten volumes, I have the opportunity to access some background information on the readings and to hold myself accountable by writing about them using the prompts provided by the editors.

In addition to reading the Syntopicon essays and working through The Great Ideas Program, I could read any of the seven complete novels in the Great Books set. For example, I have wanted to ready Moby Dick for years and it happens to be in the set. Rather than purchasing this book separately, I already have access to a nice copy.

The Great Ideas Program provides a survey of the contents of the Great Books but does not exhaust the contents of the set. If I take two weeks to go through each of the 150 readings, this implies a total of 300 weeks, or close to six years. Since I will definitely also read outside the Great Books in the coming years, this seems like a realistic pace to start with. I can always accelerate my reading of the Great Books but it is hazardous and potentially demoralizing to start out with plans that are too ambitious.

Robert Hutchins and Mortimer Adler believed that reading the Great Books should never end. The important thing is to get started. If you are interested in doing so, I would suggest exercising caution when purchasing these sets. Many are available on eBay but the quality will vary greatly. I would not feel a need to necessarily purchase these particular sets of books. There are other books in print, such as those in the Everyman’s Library, which I have enjoyed reading in the past.

I plan to write articles like this one in the future as well as fully formed essays on various topics found in the Great Books. However, I am not certain whether I will continue with public journal entries. I need to be able to write journal entries in an informal, low stakes manner and even if I publish them in public with that caveat, knowing that I’m sending them out to others to read has been somewhat of an impediment in recent weeks. I have yet to make a final decision on journal entries, but you can expect more articles as I proceed with what I hope will be a multi-year project.

A note on translations: I do not feel an obligation to necessarily use the translation provided in the Great Books set. In many cases, new translations have been released since 1952 which are considerably easier to read. For example, the translation of Montaigne’s essays in the Great Books is much more challenging for me to read than newer translations by Donald Frame and M.A. Screech. Similarly, since I enjoyed Emily Wilson’s rendering of The Odyssey, my next reading of The Iliad is likely to be her new translation rather than the copy included in the Great Books.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.