Kidney Failure and the Dialysis Industry

A brief history of a vital medical procedure

Note to Readers: This article is the first in a two-part series about dialysis and kidney failure. The first article describes the history of dialysis and the industry that developed to deliver this vital service to patients. The second article examines DaVita, a publicly traded company operating within the dialysis industry.

Introduction

The human body provides us with two kidneys, but we only need one of them to live a normal life. On a daily basis, the kidneys process an amazing 190 quarts of water and 3.3 pounds of salt.1 The kidney’s job is to act as a filter, eliminate wastes into the urine, regulate blood pressure, and perform other vital functions. All of the blood in our body passes through the kidneys about forty times per day.2 Without the services provided by one or both of these vital fist-sized organs, we would quickly die.

When the kidneys lose their ability to function for any reason, toxins begin to build up in the body. Below a certain threshold of function, death will occur in short order as the body is overwhelmed by the lack of filtration that the kidneys provide. The failure of the kidneys is known in the medical community as end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

We do not know for certain why the human body maintains redundancy when it comes to the kidneys, but we should be thankful for it. In case of traumatic injury to one kidney, the other can continue to function normally. In addition, having a “spare part” allows us to give the gift of life to friends or family members who require kidney transplants. About a third of kidney transplants come from living donors. Those who do not have a living donor face a median waiting time of four to five years for a kidney from a deceased donor assuming they are healthy enough to qualify for a transplant.3

The reality for most patients suffering from kidney failure is that they must undergo some form of dialysis in order to continue living. Dialysis is an artificial method to replicate the filtration process normally provided by the kidneys. Some patients undergo dialysis temporarily while they await a transplant while others who have too many adverse risk factors for surgery will rely on dialysis for the rest of their lives. The most common form of dialysis involves having blood filtered through a hemodialyzer in a medical facility three times per week for four hours per session.

Before the availability of dialysis, kidney failure was a certain death sentence. However, the invention of dialysis, along with the practical methods needed to administer it on an ongoing basis, now makes it possible for such people to live relatively normal lives for years or even decades after their kidneys cease to function.

This article is divided into three parts. First, a brief history of the invention of dialysis provides the necessary baseline knowledge to understand the industry. Second, today’s state-of-the-art options for dialysis treatment are discussed. Finally, the current population suffering from ESRD is described along with role of Medicare in funding their care. This provides insight into the market for dialysis services.

The dialysis industry is nearly certain to continue growing for a long time to come because the number of patients suffering from ESRD is skyrocketing. Dialysis is a service that patients literally cannot live without — the very definition of a service with non-discretionary demand. Ongoing demand for the procedure is certain and well-established streams of funding guarantee access to dialysis for all Americans. However, there are certain risks inherent in this industry which potentially limit its appeal for investors.

The Early History of Dialysis

The November 1962 issue of Life Magazine describes the harrowing story of several individuals struck down by kidney failure in the prime of their lives.4 One of the individuals was John Myers, a 37 year old man suffering from uremic poisoning and congestive heart failure, two symptoms of ESRD. Mr. Myers had been told of his kidney problems upon discharge from the Army in 1945, but he had sufficient kidney function to live normally for another sixteen years. ESRD can manifest its symptoms very suddenly. Just months after first noticing symptoms, Mr. Myers found himself at the brink of death on Christmas Day 1961.

The first “artificial kidney” was actually developed more than two decades before Mr. Myers was struck down with ESRD, but its availability for long-term use was very limited. Dr. Willem J. Kolff developed the first hemodialysis machine in 1939 in the Netherlands and treated his first dialysis patients while his country was under Nazi occupation.5 However, using this machine required a surgical procedure for each dialysis session to access an artery and vein. Patients could not withstand repeated access, so the procedure was limited to cases with acute, but temporary, kidney problems who only needed temporary dialysis.

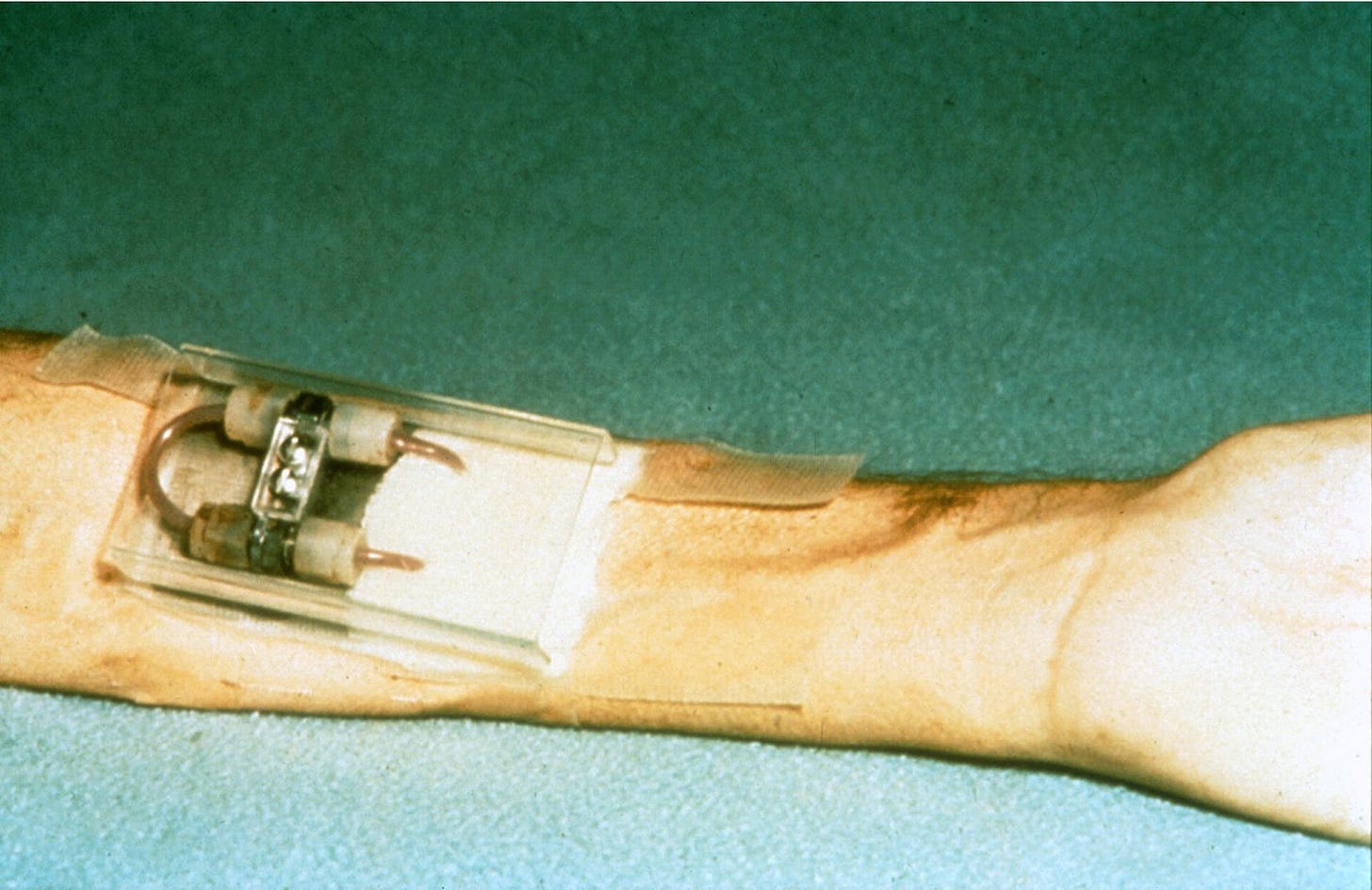

The breakthrough making the long-term treatment of ESRD possible came in 1960 when Belding Scribner developed a shunt that eliminated the need for surgery prior to each dialysis session. The Scribner shunt utilized advances in teflon tubing to access an artery and vein. During dialysis, the artery and vein would be connected to the hemodialyzer machine. After the session, a teflon tube would connect the artery to the vein in a “U shape” until the next dialysis session. Although the patient would have to tolerate this extruding device on the arm and keep it clean, the trauma of repeated surgeries was eliminated making long-term use for ESRD possible for the first time.

The first use of the Scribner shunt took place in early 1960 when Clyde Shields underwent dialysis for 76 hours. A Boeing machinist dying of ESRD, Mr. Shields responded very well to treatment and stayed on dialysis for eleven years before dying of a heart attack in 1971. By the time Mr. Myers began dialysis in late 1961, the procedure had been refined and several patients in the Seattle area were undergoing overnight dialysis twice a week. After starting dialysis, Mr. Myers was able to resume his prior work and family life.

At the time of the Life Magazine story in November 1962, long-term dialysis was restricted to the Seattle area and helped only a small number of patients even though the treatment had proven its viability. A big part of the issue was related to funding:

Today Seattle’s Swedish Hospital cares regularly for five patients who wear the tubes. In addition to Myers, they are a car salesman, a physicist, an engineer and an aircraft worker. By the end of this year there will be five more. All 10 will be part of an unprecedented two-year trial program to determine whether and how the rugged and expensive new treatment—at present the cost is $15,000 a year per patient—can be made feasible on a mass, nationwide basis.

According to the inflation calculator provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, $15,000 in 1962 dollars is equivalent to approximately $143,000 in 2022 dollars. With the median family income of $6,000 in 1962, very few people could come close to affording this expensive procedure and many resorted to seeking help from benevolent employers, community groups, fundraisers, and religious organizations.

By 1965, the cost of a year of dialysis had dropped to $10,000 while median family income was $6,900. The Life Magazine article in 1962 estimated that 100,000 people per year were dying of ESRD and the presence of a viable long-term treatment became more widely known. In 1965, NBC ran a documentary entitled “Who Shall Live” that highlighted both the lifesaving promise of dialysis and the extreme difficulty ESRD patients were having when it came to paying for the treatment.

During the early years of dialysis, a patient selection committee decided the fate of applicants based on a variety of factors. Patients were generally under the age of 45 and, aside from kidney failure, were in otherwise good health. Scarce resources were only expended on individuals who appeared to have a good chance of long-term survival and, subjectively, were deemed capable of “contributing to society”. Of course, this excluded the vast majority of ESRD patients, many of whom were elderly people who did not work and had other co-morbidities.

Following the NBC documentary, pressure quickly mounted for the federal government to get involved.6 Proponents of federal funding pointed out that ESRD was the only example of a fatal condition where long-term survival hinged on access to a miraculous new treatment that had been proven effective over a number of years. It was cast as a moral imperative to provide the necessary funding.

The Medicare program was created in 1965 to provide healthcare funding for the elderly. Initially, coverage of ESRD was discussed in the context of universal health insurance proposals, but it was incorporated into Medicare itself in 1973.

ESRD remains the only medical condition under which patients of any age can qualify for coverage under Medicare. Few people realize that the United States does have universal health care … if you suffer from one specific condition. Furthermore, those under the age of 65 who qualify for Medicare due to ESRD are also entitled to receive Medicare coverage for all other conditions as well, not just kidney related services.

This quirk of Medicare coverage has heavily impacted the economics of the dialysis industry over the past fifty years.

Current Options for Dialysis Treatment

Medical technology has progressed dramatically over the past half-century. Although overnight dialysis is still an option, most patients opt for daytime hemodialysis treatments three times per week in an outpatient clinical setting. Each treatment takes approximately four hours, a significant improvement from the time requirements facing patients decades ago.

Hemodialysis remains a complex procedure that uses the same basic principles invented by Dr. Kolff in 1939, albeit with much more modern equipment that is quicker, safer, and less traumatic for patients. The exhibit is a useful explanation of how the hemodialysis process works:

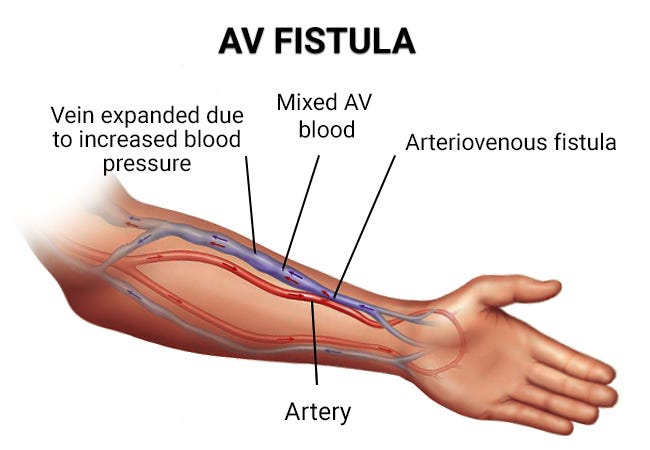

Modern vascular access methods commonly involve using an arteriovenous fistula which is normally created during an outpatient surgical procedure. Once properly healed, this connection can withstand long-term use for hemodialysis. In cases where a fistula is not possible, an arteriovenous graft can be used which resembles a modernized evolution of the Scribner shunt.

For obvious reasons, it is undesirable to have to travel to a clinical setting to receive time-consuming dialysis treatments three times per week. For this reason, ever since the development of hemodialysis in the 1960s, home-based hemodialysis has been an option. By 1964, home-based dialysis was being used by several patients and the technique was proven to be effective provided that the patient had adequate support that was usually provided by family members.7

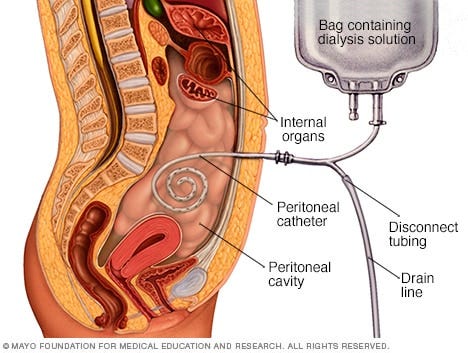

Although home-based hemodialysis is available, another type of home-based dialysis exists that does not involve the direct filtration of blood through a hemodialyzer. Peritoneal dialysis involves the circulation of dialysate, a cleaning solution, through a patient’s abdominal cavity. This dialysate solution absorbs waste from blood vessels in the abdominal lining which is then circulated back outside the body and disposed of. The following exhibit illustrates peritoneal dialysis:

While peritoneal dialysis avoids the need to use needles to access the vascular system directly, it does involve the insertion of a permanent peritoneal catheter which must be kept clean, and the equipment must be kept scrupulously clean by the patient or his or her family members. Significant training is required to perform any type of home-based dialysis successfully. The risk of serious infection cannot be ignored.

The Scope of the Problem

The 1962 Life Magazine article estimated that 100,000 people per year would die of ESRD without the lifesaving treatment offered by dialysis. This was at a time when the population of the United States was approximately 185 million.

Today, the population of the United States is estimated to be approximately 332 million and the number of patients with ESRD exceeded 809,000 in 2019, the last year for which figures are available. The problem is very large and is getting much worse as we can see from the chart below:

To say that we have an epidemic of ESRD in the United States is no exaggeration. From 2009 to 2019, the number of ESRD patients skyrocketed by 41 percent.

A kidney transplant is the best option for patients who can withstand surgery. Those who do not have a living donor and are deemed candidates for surgery must join a waiting list. At the end of 2019, 78,690 patients were on the waiting list for a kidney. There were 24,502 kidney transplants in 2019, an all-time high.8

The numbers demonstrate that the vast majority of the 800,000+ patients with ESRD must utilize the services provided by the dialysis industry in order to continue living. There simply are not enough available kidneys to supply those who are on waiting lists and many patients are just too sick to withstand transplants because, in addition to kidney disease, they often have other co-morbidities such as heart disease.

Unfortunately, the situation is likely to get even worse in the future.

The leading causes of chronic kidney disease are diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. The CDC estimates that 37.3 million Americans have diabetes. Of this number, 8.5 million had undiagnosed diabetes and were not aware of their condition. In addition, the CDC estimates that 96 million Americans over the age of 18 have pre-diabetes, with the vast majority of these people unaware of their condition. These are catastrophically high numbers as a percentage of the population.

Chronic kidney disease can progress for many years before reaching the point where symptoms emerge. The fact that so many Americans are unaware of their diabetes or pre-diabetes means that they are unlikely to make lifestyle changes to forestall the onset of ESRD. We can expect the number of ESRD patients to continue rising for a long period of time. Sadly, the number of diabetic and pre-diabetics in the United States virtually guarantees a rising number of patients who will require dialysis in the decades to come. Only a breakthrough in the field of artificial implantable kidneys or xenotransplantation could alter the upward demand for dialysis services.

As mentioned earlier, Medicare covers care associated with ESRD for Americans regardless of age. For most patients, there is a three month waiting period before Medicare coverage begins. This means that coverage begins on the first day of the fourth month of dialysis treatments.

Traditional Medicare covers 80% of the cost of treatment with the patient responsible for the remaining 20%. In cases where the patient has private health insurance, there is a 30 month coordination during which the private insurance plan continues to pay for kidney related coverage. Total spending for Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD was $51 billion in 2019 and has been rising in inflation-adjusted terms in recent years, as the following chart shows:

The fact that Medicare provides this coverage makes the government the dominant payor in the dialysis industry. On one hand, the presence of a reliable source of payments for dialysis services is obviously helpful for the industry. But on the other hand, the government has massive power when it comes to negotiating reimbursement rates and other policies for companies operating in this sector.

Conclusion

The presence of unfortunate longstanding demographic trends in the United States makes it nearly certain that the demand for dialysis treatment will continue to rise in the years and decades to come unless a medical breakthrough in the field of implantable artificial kidneys or xenotransplantation occurs. There are simply too many Americans with diabetes and pre-diabetes to alter the trajectory of ESRD anytime soon. It would take decades of lifestyle and cultural changes to bring the numbers down in a material way.

Providing dialysis services to ESRD patients is a necessary service and an industry has developed for this purpose. Although one wishes that it was not the case, the industry benefits from the fact that the number of patients needing their services will increase for the foreseeable future. However, there are risks associated with operating in a business where the federal government is the dominant payor for services.

The purpose of this article was to set the stage for a discussion of DaVita, one of the two major players in the dialysis industry in the United States. Please click the following link to read the second article in the series:

DaVita: An Essential Provider of Dialysis Services

The Rational Walk is a reader-supported publication

To support my work and to receive all articles that I publish, including premium content, please consider a paid subscription. Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this newsletter constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson, p. 154

WebMD: Picture of the Kidneys, Accessed on May 13, 2022.

United States Renal Data System (USRDS) 2021 annual report: “Among patients who were initially waitlisted in 2014, the median wait-time was 51.6 months, slightly lower than the corresponding estimate in the previous year (55.9 months)” Accessed on May 14, 2022.

The November 1962 issue of Life Magazine has been republished by NephLC, a nephrology journal. The article is also available in its original format via Google Books.

What Scribner Wrought: How the Invention of Modern Dialysis Shaped Health Law and Policy by Sallie Thieme Sanford. Retrieved on May 12, 2022.

Political developments during the 1960s and early 1970s are covered extensively in The Early History of Dialysis for Chronic Renal Failure in the United States: A View From Seattle by Christopher R. Blagg, published by the American Journal of Kidney Diseases on March 1, 2007. Retrieved on May 12, 2022.

See The Early History of Dialysis, listed above. A discussion of early home-based dialysis begins on page 486.

USRDS 2021 Annual Report.

Very well put together historical article on kidney failure. Can’t wait to read part 2.

Fascinating, informative article. Loved every word of it!