Insurance Loss Reserve Estimates

The ability to accurately estimate loss reserves is a core competency for any well-run insurance company. Progressive provides a useful case study in loss reserving practices.

Introduction

Insurance companies accept premiums in exchange for assuming the risk of loss from events taking place in the future.1 Policyholders trade cash up front for protection against losses that, in many cases, would be financially ruinous in the absence of coverage. Insurers hope to underwrite profitably over their entire risk pool by earning premiums that, in aggregate, exceed loss payouts and expenses associated with running their insurance operations. In addition to underwriting profits, insurers generate income from investing funds that will eventually be used to pay claims.

It is no exaggeration to say that insurers are selling a promise to policyholders when they accept premiums. The customer receives nothing more than a piece of paper indicating coverage for a period of time. This is an alluring business model but the downside is that the insurer does not have certain knowledge of its ultimate exposure until sometime after a policy expires.2 As a result, insurers must devote much careful attention toward estimating the reserves required to pay anticipated future losses.

Maintaining accurate loss reserving practices is one of the most crucial functions for any insurance company. An insurer that does not have a good track record of loss estimation cannot have confidence that it is pricing new and renewal policies at a level that will produce acceptable levels of profitability. In addition, loss reserves are recorded as a liability on the balance sheet. A chronic failure to accurately estimate loss reserves could make it more difficult to invest policyholder funds appropriately.3

Investor confidence will inevitably suffer if reserves prove to be inadequate. Investors often value insurers based on a multiple of book value. Inadequate reserves have the effect of inflating reported book value. Insurance companies with a history of adverse reserve development are likely to trade at a lower multiple of book value compared to insurers with a history of adequate reserving or favorable reserve development.4

Owners of public companies have a limited view of how management operates the business. Executives are reluctant to speak to shareholders due to fears of violating selective disclosure regulations. Disclosures in the form of press releases and SEC filings are typically less than fully illuminating and quarterly earnings calls normally focus more on short-term drivers of profitability than long-term strategic topics.

The opaque nature of investing in public companies is not an insurmountable challenge. Investors can focus on simple businesses where there is little need for estimation in financial results. When it comes to insurers, investors can opt to focus on companies engaged in short-tail lines where loss reserving problems will show up relatively quickly. For example, inadequate loss reserving is going to show up far more quickly for a property insurer than for a reinsurer specializing in asbestos liabilities.

Automobile coverage is a good example of short-tail insurance. When auto-related losses occur, they are likely to be reported very quickly. The cost of repairing vehicles is usually known within weeks or months at the most. While it can take longer for claims related to bodily injury to be finalized, the overall nature of auto insurance provides relatively quick feedback related to loss reserve adequacy.

Progressive focuses primarily on short-tail auto insurance and management provides more data to the public compared to most publicly traded insurers. In addition to annual and quarterly reports, Progressive publishes monthly results with useful data. Management also publishes a detailed loss reserve report every two years. I have found Progressive’s disclosures to be far more illuminating than the industry norm.

In early August, Progressive held a conference call (webcast, slides, transcript) to explain how loss reserving works in quite a bit of detail. I have followed the insurance industry for a long time, but always from the perspective of an individual investor without access to the nuts and bolts of how the reserving process works at the claims level and rolls up to the aggregate figures we see on financial statements.

It was interesting to listen to Progressive’s actuary discuss how reserves are set and adjusted. Following the actuary’s presentation, there was a valuable discussion about cohort pricing. The profit profile of a policyholder varies over the lifetime of the relationship and the distribution channel. Readers with a serious interest in the insurance industry will want to listen to the webcast or read the slides and transcript.

In this article, I briefly discuss Progressive’s recent reserving results following by highlights from the presentation that I found interesting. The goal of this article isn’t so much to analyze Progressive’s recent results as it is to walk through how the management of a successful insurer thinks about loss reserving and cohort pricing.

Recent Results

Progressive’s report on loss reserving practices, published in late 2021 makes clear the importance of accurate loss estimation when it comes to setting policy pricing:

“Unlike most industries, insurers do not know their costs until well after a sale has been made. Thus, one of the most important functions for an insurance company is setting rates or pricing. The goal of our pricing function is to properly evaluate future risks the Company will assume but has not yet written. Estimates of future claim payments are essential for accurately measuring Progressive’s underwriting profit and for determining whether pricing changes are needed to achieve the Company’s underwriting target. Reserve estimates that are too low can lead to the conclusion that pricing is adequate when it is not, and additionally, we may experience unprofitable growth. Reserve estimates that are too high may lead to inflated prices, potentially limiting our ability to attract and retain customers.”

I added the emphasis to the quote in order to highlight the balance that must be struck. Management does not want to risk recording inadequate reserves but it is also undesirable to record significantly redundant reserves. If loss estimates are too high, then the group responsible for pricing will regard this information as a signal to raise premium prices in order to maintain profitability targets. The result will be slower growth or perhaps even negative growth. Progressive’s stated goal is to grow policies in force as quickly as possible consistent with achieving a 96% combined ratio.5

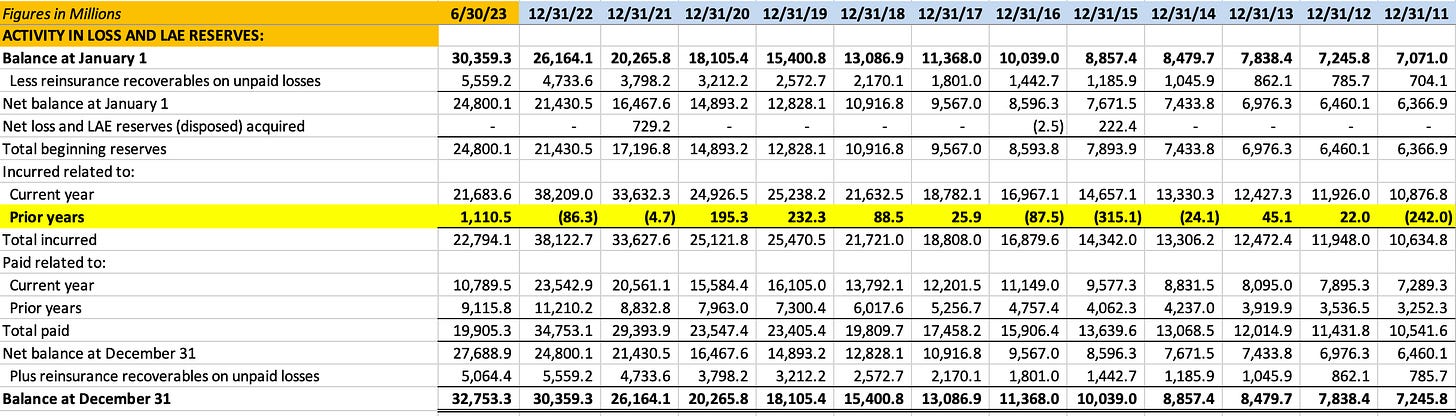

In my report on Progressive last year, I presented some data on the company’s loss reserving history. The exhibit below is an updated history of activity in loss and loss adjustment expense reserves through the end of the second quarter of 2023:

The highlighted row in the exhibit displays prior year development and is referred to as either favorable or unfavorable reserve development in management’s discussions of financial results. Positive figures indicate unfavorable reserve development while negative figures indicate favorable development.

We can see that development related to prior years, whether favorable or unfavorable, has tended to be relatively small compared to overall reserves on the balance sheet. However, Progressive experienced very significant unfavorable development of $1,110.5 million during the first six months of 2023. In the 10-Q, management attributed $870 million of the unfavorable development to personal auto lines.

In Will Progressive’s Growth Strategy Pay Off?, published in July, I wrote about the company’s growth strategy and how it paid off in terms of increasing policies in force by 11.6% over the past year. Much of this gain apparently came at the expense of GEICO, Progressive’s main competitor. In retrospect, it appears that at least part of this growth was due to Progressive underestimating the cost of taking on new business in an inflationary environment. This is the context in which management addressed analysts and investors in the early August discussion of reserving practices.

Loss Reserving Discussion

I credit Progressive’s management with addressing the unfavorable development experienced during the first half early in the presentation. From an investor’s standpoint, the important question is whether there is something systemically broken in management’s process or if the problems can be explained by unusual factors that are likely to be non-recurring in nature. Apparently, almost half of the unfavorable development in the personal lines segment was due to problems in Florida:

CEO Tricia Griffith explained the situation as follows:

“The majority of personal lines adverse development can be placed into two categories: Florida and fixing vehicle coverages. Florida's prior year adverse development accounts for just over 40% of the 4 points of prior year development.

While we continue to be optimistic that March's new legislation will result in lower loss costs over time, the short-term effect has been a significant increase in attorney representation largely in medical coverages. Our data has matured each month since the bill passed, which has allowed us to continue to fine-tune reserving in the face of changes to Florida's ultimate loss costs.”

Progressive is hardly alone in facing difficulties in the Florida insurance market, and the troubles are not restricted to automobile insurance. According to Bankrate, Florida drivers are now paying an average of $3,183 for a year of full auto coverage, far higher than the national average of $2,014. Insurers have had trouble raising premiums fast enough to stay ahead of skyrocketing costs in Florida and elsewhere. Progressive appears to have been caught up in the whirlwind of cost escalation in Florida and time will tell whether they have increased premiums enough in response.

Following the CEO’s comments, Gary Traicoff, Progressive’s Corporate Actuary, went into more detail on the nuts and bolts of the reserving process. After providing a ten year history of Progressive’s growth in gross reserves, which currently stand at nearly $33 billion, he presented the following slide:

The chart on the left shows the breakdown of net reserves. Over two-thirds of net reserves are case reserves which are estimates of amounts needed to pay claims that have already been reported to Progressive but have not been fully paid out. Seventeen percent of net reserves are associated with Incurred But Not Reported (IBNR) reserves to account for claims that management estimates have occurred but have yet to be reported to claims adjusters and recorded in Progressive’s information systems. The remaining sixteen percent of net reserves account for expenses associated with settling claims — for example, paying claims adjuster salaries and attorney costs.6

From the perspective of an outsider not privy to the inner workings of the company, investors typically see management’s efforts to determine reserves distilled down to just a few numbers each quarter. The presentation makes the point that the figures reported to shareholders represent a roll-up of numerous detailed reserve reviews conducted every month. 25-30% of reserves are reviewed monthly while approximately 85% are reviewed quarterly.

Gary Traicoff’s discussion covering slides 18-27 walks through the process of how reserves are initially estimated, in aggregate, for a given accident year and subsequently revised over time. I recommend listening to his explanation in full.

Due to the short-tail nature of auto insurance, ultimate losses are usually known within two years of the end of an accident year, with reserve development tilting toward medical and liability coverage as claims age. During periods of unexpected inflation in costs such as vehicle repair and medical care, it is likely that an insurer will have to record unfavorable development. It is also likely that the premiums paid in advance by policyholders will prove inadequate under such conditions.

I found the discussion of the pathway of a case reserve example starting on page 30 particularly interesting. In this part of the presentation, Gary Traicoff walks us through what actually happens when a specific accident is reported to Progressive.

When a case is initially reported, the claims adjustor typically has limited information and must make a very rough estimate. In addition to the estimate provided by the claims adjustor, an algorithmic estimate is calculated using predicting modeling techniques based on characteristics of the claim and the company’s experience with claims that had similar characteristics.

As time passes, more information is received which can impact both the human and algorithmic claims estimate. In addition, inflation factors are applied as time passes to recognize that more dollars will be needed to satisfy the company’s obligations. Adverse events such as the introduction of attorneys into the process increases case reserves. At each point in the process, the figures are updated to reflect management’s expectation of the true liability that exists. The final slide in a series showing the progression of this hypothetical case illustrates its evolution over seven months:

What’s interesting about this example is that the case reserve exhibited unfavorable development for several months as various events occurred that caused management to raise the expected eventual cost. Ultimately, the claim was settled for less than the final estimate which resulted in favorable development. It is apparent that this type of volatility at the individual case level is not unusual. However, Progressive is working with millions of policyholders and, averaged out over all claims during a given period, one can expect the experience of human claims adjustors and algorithmic estimates to produce reasonable results during times when unanticipated inflation is less severe.

Gary Traicoff concluded his presentation by pointing out that, as Chief Actuary, he has “complete decision-making authority” on reserves and that there are checks and balances in place. Importantly, he meets on a quarterly basis with the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors to discuss results and recent trends and his team meets with the external auditors who certify Progressive’s financial statements. It does not appear that the CEO or other members of management have the ability to put their thumb on the scale to “hit” quarterly numbers by manipulating reserves.7

Cohort Pricing Discussion

Progressive’s stated objective is to grow as fast as possible consistent with achieving a 96% combined ratio. It is important to understand how the mix of an insurer’s business impacts the combined ratio over time and how rapid growth can make it more difficult to meet the combined ratio target in the short run. Jim Curtis, Progressive’s Personal Lines Controller, presented a series of slides about cohort pricing that illustrate the dynamics at work.

Progressive seeks to price each policy to achieve a lifetime target that is consistent with the overall goal of generating a 96% combined ratio. The lifetime value of a policy includes the initial term when the new business is obtained followed by all renewal terms until the customer eventually cancels the policy.

Acquiring new customers is expensive and tends to be unprofitable during the initial policy period. With the direct channel, this is primarily due to the cost of acquiring the customer, most significantly represented by advertising expenses. Whether a new customer is acquired via direct or agency channels, the initial term also usually has a higher loss ratio. This dynamic is illustrated in the following chart:

As we can see, new business will have a combined ratio well above the target initially but the below target combined ratio as the policy seasons over time will bring the lifetime costs down to an acceptable level.

The following slide shows an example of a policy priced to yield a lifetime combined ratio of 96% illustrating how the components of the combined ratio develop over time:

This example assumes that the customer will renew five times. Including the initial term, this implies that the customer would stay with Progressive for six terms, or three years since insurance is normally purchased in six month increments. It is easy to see that if the customer continues renewing long into the future, this will result in the lifetime combined ratio falling below target assuming that there aren’t unusual losses. The cost of acquiring the customer is one-time and need not be repeated.

The difference between profitability for the initial term and renewals is less dramatic for the agency channel because acquisition costs remain for renewals in the form of commissions. However, a lower loss ratio for seasoned renewal business still acts to bring the lifetime combined ratio down over time barring large loss events. A number of slides are provided to illustrate how this plays out in the direct and agency channels.

The main takeaway from this discussion is that during periods of high growth, we can expect the combined ratio for Progressive to be higher than during period of low growth. So, it is not necessarily unusual to see elevated combined ratios when policies in force are rising rapidly, as has been the case over the past year. While it is true that Progressive was behind the curve on pricing and did not expect inflation to be so severe, what’s done is done and the acquisition costs of the new business has already been incurred. Assuming customers do not defect in response to necessary premium hikes, they should produce, in aggregate, better profitability going forward.

One could view the discussion of cohort pricing to be an attempt to explain away recent poor performance but the information presented was logical and in keeping with my understanding of the significant costs associated with direct customer acquisition. In the short run, it is possible for an insurance company to severely cut back on advertising, as GEICO has, but at the cost of ceding market share.

It is interesting to observe that GEICO and Progressive have made very different decisions regarding growth over the past year. From the outside looking in, I find it difficult to determine which management team made the better call. In my mind, the question is whether the customers Progressive attracted recently will stick around as management continues to increase premiums, something that Tricia Griffith clearly intends to pursue aggressively in the second half of the year.8

Further Reading on Progressive

In December, I published a detailed write-up on Progressive. In May, I wrote about the ongoing competition between Progressive and GEICO and in July I wrote about Progressive’s aggressive posture in the auto insurance industry over the past year.

If you found this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider referring a friend to The Rational Walk.

Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

No position in Progressive.

The typical insurance business model accepts premiums in exchange for taking on future risks. However, there are specialized types of insurance that accept premiums in exchange for accepting risks that have taken place in the past but are of indeterminate magnitude. Title insurance and retroactive reinsurance are two examples of insurance covering adverse events that have taken place in the past.

Insurers are responsible for covered losses during a period of time defined in the policy. There is often a delay between the time of a loss and when the policyholder notifies the insurer. In some cases, notice of a loss incurred during the policy term could arrive after the end of a policy term. Insurers maintain a reserve for claims that have occurred but have not been reported. This is known as Incurred But Not Recorded (IBNR) reserves.

For example, some insurers aim to invest policyholder float in fixed-maturity investments with the duration of the investments matching the duration of expected liabilities while investing shareholders’ equity in stocks. Underestimating loss reserves will lead management to underestimate the amount of funds that will be necessary to pay out claims and to overestimate the amount of shareholders equity available for investment in stocks. A sudden demand to pay out additional claims could result in a situation where stocks would need to be liquidated at a loss to cover unexpected claims. Underestimating loss reserves could also lead management to return more capital to shareholders than would be prudent, ultimately leaving the insurer undercapitalized from a business and regulatory perspective.

Insurers conduct periodic actuarial reviews of loss reserves. If a review indicates that loss reserves for a prior accounting period were not adequate, the insurer must record adverse loss development during the current accounting period. Conversely, if reserves for a prior accounting period were more than adequate (also referred to as redundant), the insurer records favorable loss development during the current accounting period. The goal of a well-run insurer is to minimize occasions where adverse loss development must be recorded.

The combined ratio is the sum of an insurer’s loss ratio and expense ratio. An insurer with a 96% combined ratio will pay out $960 in losses and operating expenses for every $1,000 of earned premiums, achieving a $40 underwriting profit.

Readers interested in a detailed discussion of case reserves and IBNR should review Section II of Progressive’s report on loss reserving practices.

I’m not suggesting that Progressive’s management would attempt this in the absence of checks and balances but it is always a good practice to have robust protections in place.

Slide 6 of the presentation shows Progressive’s recent history of rate changes. During the call, CEO Tricia Griffith stated that she intends to increase rates by 6% during the second half of the year in addition to the 11% rate hike taken during the first half.

I am a long time claims adjuster and found this article due to searching around for what other companies have published in the past. I recently resigned from a relatively new company due to many red flags including how they reserve. One of those being that they often don’t. 😅