What’s so great about podcasts?

The idea of a host chatting with guests expressing interesting points of view dates back nearly a century to the dawn of radio technology. Yet, for some reason, we appear to be in a golden age of talk radio delivered via podcasts. In just over two years I have gone from listening to zero podcasts to around a dozen per week, usually while doing things that make reading difficult or impossible.

It is through podcasts that I have been introduced to a number of brilliant young people who are involved in new technologies mostly based on the blockchain.1 The world of cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens are not weird, esoteric topics for these individuals, most of whom are either entrepreneurs in the space or investors in cryptocurrencies or other blockchain based digital assets. Their enthusiasm is obvious and often contagious, and you get the sense that they envision of world of no upper bounds constraining the future.

Although it is obvious mathematically, sometimes it is easy to forget that today’s 22-year-old was born in 1999 and what that implies regarding their frame of reference and life experiences. If you bring up the dot-com boom and bust to someone born in 1999, they will not relate to the events of those years just as I cannot fully relate to the events of the 1973-74 bear market.

Sure, you can read about historical events.

You can listen to other people talk about their experiences during those events.

You can even watch news coverage of events.

But you can never feel what it was like to experience an event that you do not recall.

You can only imagine what it might have been like and how you hope you would have reacted to it. You have to use your imagination coupled with the facts that you have learned from others.

Should young people listen to older generations who lived through the dot com bubble? Certainly, it would seem wise to do so and learn whatever lessons are available and can be understood vicariously. Although the 1973-74 bear market took place when I was very young, I still read about it before I started investing, most memorably in Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist. But Warren Buffett’s experiences of the early 1970s felt like ancient history to me in 1995.

If you stop to think about it, was the world of 1973-74 so different from 1995? Obviously, technology had improved but 1995 was literally just at the start of the internet revolution. I graduated from college in that year having spent considerable time using microfiche machines in the library, a technology not dissimilar from what a college student of the early 1970s might have used. Most of my research was accomplished by reading physical books.

Of course, we had word processors and computers and I had a university email account. But the age of the computer as a portal to all of the information known to mankind was just dawning. The idea of having a supercomputer in your pocket was inconceivable.

Someone born in 1999 has never known a world without the internet and was likely introduced to smart phones and tablets while still in elementary school. A person in her early twenties can read about how people obtained information and communicated prior to the age of the mobile phone but cannot possibly relate to it. And because the past seems so radically different from the present, it must be tempting to think that nothing much can be learned from the past that is relevant to where the world will be going over the next several decades.

One experience that I don’t think can be understood vicariously is how it feels to lose money that you have worked hard to save over a long period of time. Regardless of the progress of technology, losing money obtained through hard work doesn’t feel any different today than it did 25, 50, 100, or 1,000 years ago. It has always felt like a punch to the gut. Reading about other people losing money can never replicate that feeling.

By the time I graduated from college in 1995, I had saved about $25,000 from various jobs dating back to delivering newspapers a decade earlier. I was fortunate enough to never lose that money, either through temporary losses due to market fluctuations or permanently.

But this was not a function of any particular skill or wisdom. I simply came of age at a time when financial assets were appreciating rapidly, and I dodged the dot com bust through a combination of luck and reading the writings of Ben Graham and Warren Buffett.

My first major reversal, involving losses of very large sums of money (to me), came in the 2008-09 bear market well over a decade into my professional career, and my losses mostly ate into the investment returns earned over the prior decade.

If my first major reversal had come in my early 20s and I had lost what I had saved delivering newspapers and working minimum wage jobs, there is no doubt that my mindset would have been permanently impacted. In theory, there is no economic difference between losing investment gains and losing money you literally had to sweat to earn. In practice, there certainly is a psychological difference for most people.

No two periods of history repeat exactly but it is difficult for someone who observed the dot com bubble to not see significant “rhyming” when it comes to the frenzy we are seeing today in the cryptocurrency and NFT spaces, not to mention the garden variety bubbles in stocks of companies with no earnings and no realistic prospect of future earnings. Yet, nothing we say to a person who was born at the turn of the century will have much relevance because, to them, we are talking about ancient history — a world totally different from what exists today.

I should point out that it is not entirely clear whether young people would be well served listening to the warnings of those of us who see parallels between today and the dot-com bubble. The time horizon of someone born at the turn of the century literally extends almost to the turn of the next century. The world they create will be up to them, the technologies that they create may be inconceivable to older people today, and maybe they are right about more than we might think.

Seventy years ago, Warren Buffett graduated from Columbia having received the first A+ that Benjamin Graham had ever awarded to a student in his 22 years of teaching. When Buffett offered to work at Graham’s investment firm for free, Graham turned him down. Both Graham and Buffett’s father advised him to avoid entering the investment business.2

Oddly, when Buffett graduated, in 1951, both Graham and his father advised him not to go into stocks. Each had the post-Depression mentality of fearing a second visitation. Graham pointed out that the Dow had traded below 200 at some point in every year, save for the present one. Why not postpone going to Wall Street until after the next crash, his heroes counseled, and meanwhile get a safe job with someone like Procter & Gamble?

It was awful advice — violating Graham’s tenet of not trying to forecast markets. The Dow, in fact, never went under 200 again. “I had about ten thousand bucks,” Buffett noted later. “If I’d taken their advice I’d probably still have about ten thousand bucks.”

The older generations are always going to be informed by their own life experiences and the counsel they provide to the next generation will always be influenced by those experiences. I am sure that Warren Buffett did not casually dismiss the advice of his father and his teacher, but he plowed ahead regardless.

I am quite sure that young people who are outright speculating on stocks or various crypto assets will eventually experience what outright speculators have experienced throughout history.

It’s only a matter of time.

But we need to differentiate between a 22-year-old casually trading stocks on an app with the much smaller group of young people actually trying to build things based on blockchain technology. Some of them will likely build things that we cannot conceive of today and have real economic value.

It is often said that many ideas of the dot com bubble were not necessarily wrong, but just early. Business models that required more bandwidth or the presence of a supercomputer in everyone’s pocket were not ready for prime time in 1999. The emergence of smartphones and super-fast bandwidth has changed the world and made previously impossible business models possible.

No one should invest in companies or technologies that they do not understand. I refuse to do so myself, but that doesn’t mean that I have to root for these new technologies to fail. To the contrary, I would be delighted if some of them succeed even if I do not personally see a path to success or participate financially. For example, the concept of a digital currency that is not controlled by a government and not subject to the value destruction of today’s fiat currencies is very attractive if it can actually work. The idea of artists being able to realize new sources of income from the sale of NFTs (as well as royalties on resales) is also very attractive.

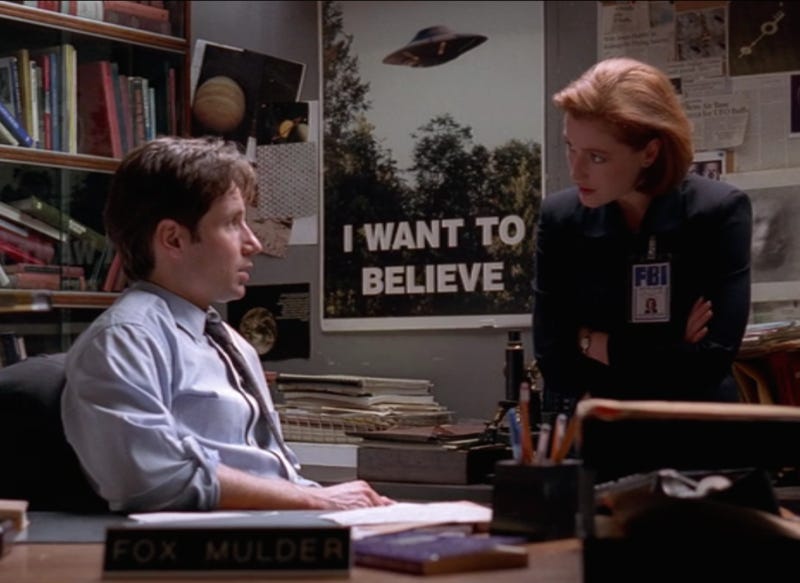

I’ll conclude by saying that, like Fox Mulder, “I want to believe” that some of these technologies will bear fruit even as I admit my ignorance and stay resolutely on the sidelines when it comes with how I invest my own capital.3

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this newsletter constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Although I have read about blockchain technologies over the years, I have not done any serious research in the field. Here’s a book review from 2017 with some of my thoughts at the time.

Excerpt from “Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist” by Roger Lowenstein, published in 1995. Pages 45-46.

This is a very good post. I just had a conversation with my 23 year old son about crypto. I echo many of your same thoughts. I will never participate in buying these coins simply because I experienced the dot com crash, not by losing money, but buy witnessing it up close. It’s hard for me to explain what it was like to him. He may need to pay tuition to Mr. Market

As someone who witnessed the rise of home computers and the internet I have always wondered how people got their information 200 years ago without even a telephone or telegraph machine. The Rothschild's got their information by employing messengers who would go places and bring back information, which seems so strange today. Even before the 1930's Joe Kennedy made his money using the telephone and talking to people. Talking to people? Who does that now?

It has been said that the amount of information we receive today in a day is more than most people received in a year 200 years ago. Just difficult to understand what that means.