The Odyssey

Homer's epic poem tells the story of how Odysseus struggled to return home after the Trojan War. It is one of the greatest stories in history.

A decade after the end of the Trojan War, Odysseus was still far from home.

Twenty years had passed since the great warrior last saw his wife and infant son before he sailed to Troy as part of an alliance that defeated the Trojans and recovered Helen whose abduction sparked the conflict. While the surviving warriors had long since returned to peaceful tranquility in their homes, Odysseus bemoaned his fate. Held against his will on an enchanted island by a beautiful goddess who promised him immortality, Odysseus wanted nothing more than to return home. He willingly accepted mortality to brave the seas alone, on a simple raft, and was nearly lost before washing ashore in a strange but hospitable land.

The Iliad is an epic poem about seven weeks toward the end of the decade-long Trojan War. The Odyssey can be considered a sequel but it is a very different story. In The Iliad, Homer goes into great detail about the traditions and horror of ancient warfare. I found it challenging to write about The Iliad for many reasons. The story portrays a culture and warrior ethos foreign to modern readers. In contrast, The Odyssey features a storyline that modern readers find easier to relate to. Of course, Odysseus encounters gods, goddesses, monsters, and other mythic creatures in his adventures, and we cannot relate to that world, but many of us know well the longing for home when we are far removed from friends and family.

While Odysseus suffered homesickness, his estate on Ithaca had been besieged by a hundred young men who were courting his wife and consuming his wealth. His twenty year old son, Telemachus, had no recollection of his father, and had yet to mature into a man capable of defending his home. Odysseus’ wife, Penelope, grieved the loss of her husband and she was ambivalent about ceding to the will of her parents and others who were pressuring her to pick a suitor and remarry. One gets the sense that Penelope liked the attention, at some level, since she gave the suitors hope by not declaring that she wished to remain single. Penelope, most likely in her late thirties, remained an attractive woman desired by her younger suitors.

This is the scene we are given at the beginning of The Odyssey as the arc of the story moves toward its ultimate resolution. Odysseus eventually prevailed and his home and family were restored to him, but not after much anguish and the intervention of the gods. The gods decide that Odysseus has suffered for too long and plans are put in motion to send him home. Calypso, the goddess holding Odysseus on her enchanted island, was ordered by Hermes to release him. After helping Odysseus build his makeshift raft, Calypso sent him on his way.

But the god Poseidon found out and tried to kill Odysseus in retribution for what Odysseus did to his one-eyed cyclops son several years before. Despite Poseidon’s best efforts, Odysseus made it to shore and was rescued by a beautiful princess. The King and Queen, after extending much hospitality to Odysseus before even knowing his name, eventually asked him to tell his story. This created an opportunity for Homer to have Odysseus tell of his adventures after Troy in a series of long flashbacks. Odysseus took the time to reminisce about the fall of Troy and the return journey with his men, a story of adventure and misfortune like few others in literature. The details of these adventures are well documented in summaries elsewhere but I will leave them out of my account. I would urge everyone to read The Odyssey for themselves rather than spoil it with attempts at a summary. Odysseus was eventually sent on his way after receiving many gifts and much honor, escorted back to Ithaca on a magical ship that steers itself.

Meanwhile, the goddess Athena sent Telemachus to see King Nestor in Pylos who extended great hospitality to the young man and then sent him on his way to see King Menelaus in Sparta. These kings told Telemachus stories of his father’s bravery. They did not know what happened to Odysseus after leaving Troy, but the trip was an important one for a young man lacking confidence and strong male role models. Telemachus returned to Ithaca just as Odysseus, disguised as an old beggar, took refuge in the home of one of his old slaves, a swineherd. From a practical perspective, Odysseus can hardly just show up at home and confront a hundred young men in the prime of their lives. A master strategist, Odysseus first kept his identity even from his own son, but eventually both the swineherd and his son learned who he is.

With Athena providing invaluable support, Odysseus and Telemachus formulated a plan to confront the suitors and reclaim their home. They had the help of two loyal slaves, but are badly outnumbered in a contest with the suitors. Odysseus, known for his cunning strategy, showed up as a non-threatening beggar. The suitors ridiculed him and treated him poorly, a major violation of cultural norms of hospitality prevalent in the ancient world. Penelope met her husband without recognizing him, and he spun a tall tale about having met Odysseus on the island of Crete years earlier. When an old slave recognized a scar on Odysseus while washing him, Odysseus prohibited the slave from revealing his identity, with help from Athena who distracted Penelope. The scene is now set for the denouement.

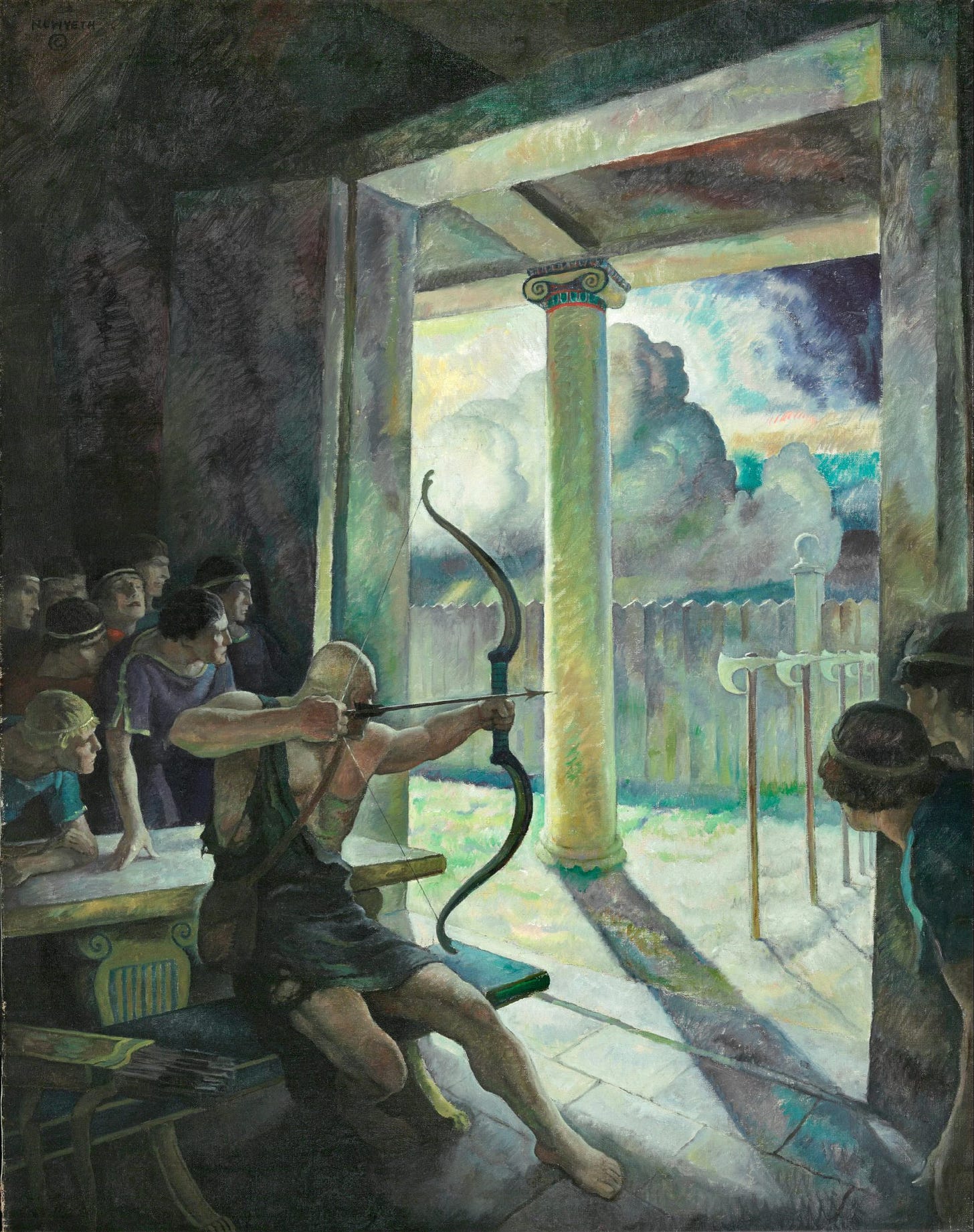

Penelope suggested an archery contest to decide which suitor will win her hand. The bow to be used was one that Odysseus left at home when he sailed to Troy. None of the suitors could even string the bow, let alone use it in the contest. Odysseus was allowed to make the attempt, amid much mockery and laugher among the suitors who believed the old man had no chance. Odysseus strung the bow and fired an arrow through the holes in a dozen axe heads lined up in a row. The suitors were amazed, but their surprise will soon turn to horror. Odysseus proceeded to pick off the suitors one by one with his arrows. When he ran out, the slaughter continued with the help of Telemachus and the loyal slaves.

In due course, all of the suitors were killed. After being forced to clean up the blood-soaked mess in the room, the disloyal servant girls, who carried on affairs with the suitors, were executed by hanging. Penelope was informed that Odysseus returned but had trouble believing that it could be true. She was only convinced after Odysseus told her how he built their bed around an old olive tree, making it obvious that he knew the layout of the inner sanctum of their home that few had ever seen. The couple was reunited at last, but the story is not over. Odysseus must go to his elderly father, Laertes, who has retreated into the hills in grief, seeking solace in manual labor. Odysseus somewhat cruelly told the old man a tall tale about his identity before admitting who he was, and father and son were finally reunited.

As the news of the suitors’ demise spread throughout the community, the angry relatives of the young men were outraged and took up arms. The story concludes as Odysseus and Telemachus, now a proven fighter, go out to face the angry mob. The slaughter begins and is only brought to an end by the intervention of Athena. The end result is that Odysseus has been restored to his rightful place on Ithaca at last and the epic ends.

Great literature is timeless because the human stories that are told resonate hundreds or even thousands of years later. This is clearly true for Homer’s epic poems. While The Iliad might be hard to relate to, especially for those who have never fought in a war, The Odyssey has something for nearly everyone. All of us can relate to being homesick. The story of Telemachus is a classic tale of coming of age in the shadow of a famous parent. We are faced with moral quandaries throughout the adventures, but never as much as when Odysseus chooses ruthless vengeance and kills the suitors. He had to reclaim his home and there was certainly going to be bloodshed, but was it necessary to kill everyone in this brutal manner? Did the disloyal servants, who were after all slaves, deserve to die because of their actions? Many of these actions are repugnant to us today, but we are steeped in the Judeo-Christian ethic that was foreign in Homer’s world.

On the other hand, we can learn something from the attitudes the ancients had when it came to hospitality for strangers. The first instinct, indeed one that was sanctioned by Zeus himself, was to assist a stranger in need. When brought into a home, a stranger must be given food and drink and be allowed to rejuvenate before being questioned about their background. This applied, to some extent, even to dirty beggars and it is why Odysseus was able to gain entry into his own home when he was disguised as one. There were obviously limits to ancient hospitality, but it seems superior to modern hospitably in many ways.

Telemachus was not a child but hardly yet a fully developed man. At the age of twenty, he resembled many young people of the modern era who have yet to find their way in the world. His story is also about lacking a strong positive male role model, something hardly foreign in modernity given increasing rates of divorce and the resulting broken homes. Grief and obvious depression prevented Laertes from playing an active role in the upbringing of his grandson, leaving him adrift. Telemachus had to make the trip to see Nestor and Menelaus because he needed strong male role models to fortify himself in order to confront the suitors. He does seem more assertive as the story develops.

Odysseus loved his wife, but he was not loyal to her. He had lengthy affairs with Calypso and Circe. Granted, they were both goddesses who gave him little choice, but I don’t think Odysseus was suffering greatly during those interludes. On the other hand, Penelope was expected to remain faithful to Odysseus for two decades, and it would have been a major issue if Odysseus had returned to find that this was not the case. When Odysseus met Agamemnon’s shade on his trip to Elysium, as told in his flashback, Agamemnon told of how he was killed by his evil wife, Clytemnestra, when he returned from Troy. Clytemnestra had carried on an affair with Aegisthus during Agamemnon’s absence. Penelope was always faithful to Odysseus, despite the double standard, and ultimately Odysseus rejected immortality on Calypso’s island to come back to her.

I read two translations of The Odyssey during a slow reading of the poem in April. I started with Samuel Butler’s translation which is included in my full set of Great Books of the Western World. I followed up with Emily Wilson’s translation which was published in 2017. I wrote in more detail about these translators in my article on The Iliad last month. Butler’s translation is much older, published in the late nineteenth century, and is in prose. He uses the names of the Roman gods which poses a bit of a challenge since I am more familiar with names of the Greek gods, but this was not insurmountable. Wilson’s poetic translation is simply brilliant and flows very well for the modern reader. I first read Wilson’s translation several years ago and enjoyed reading it again, this time much more deliberately. I also own a copy of Robert Fitzgerald’s translation of The Odyssey which I read around 2015. I only used it as a reference this time.

Emily Wilson’s translation includes an excellent introduction and useful maps. Readers who are approaching Homer for the first time should definitely opt for Wilson’s translation which also features extensive endnotes and a glossary of all characters featured in the story. This is invaluable, especially for those who are less familiar with the Greek gods.

Readers who are new to Homer might want to read The Odyssey before The Iliad even though this is out of chronological order. This is especially true for younger readers. I have a much greater appreciation for The Iliad after taking the time to really study it, but it is a far more challenging story to truly understand. The Odyssey, in contrast, is a great adventure story accessible to everyone. It is not necessary to understand all of the events of The Iliad to enjoy The Odyssey.

I did not originally intend to read Homer as part of my reading plan for the Great Books because I was already familiar with these works from prior readings. However, I am glad that I took a month to reach each epic slowly. I now feel like I have a better understanding of these poems and am better equipped to approach the works of the Greek tragedians, all of whom wrote plays for audiences that knew Homer extremely well. I will miss fewer nuances and enjoy the plays much more since I took the effort to read Homer carefully.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

I enjoyed reading your summary. I read both books in a classical literature course at Auburn but I don't remember any details.

What do you think about the story Odysseus tells about his fantastical journeys? What actually happened to him and his men? He is a cunning liar after all.

The story moves in and out of magical realms in interesting ways. The structure itself is so interesting.