The Lords of Easy Money

Christopher Leonard documents the Fed's increasingly unconventional monetary policies since the 2007-09 financial crisis.

“An entire economic system. Around a zero rate. Not only in the U.S. but globally. It’s massive. Now, think of the adjustment process to a new equilibrium at a higher rate. Do you think it’s costless? Do you think that no one will suffer? Do you think there won’t be winners and losers? No way. You have taken your economy and your economic system, and you’ve moved it to an artificially low zero rate. You’ve had people making investments on that basis, people not making investments on that basis, people speculating in new activities, people speculating on derivatives around that, and now you’re going to adjust it back? Well, good luck. It isn’t going to be costless.”

— Thomas Hoenig1

The United States Constitution defines three distinct branches of government — legislative, executive, and judicial — each vested with its own enumerated powers and designed to collaborate with the other branches to ensure that government is effective, and the rights of citizens and states are protected. However, the textbook definitions of how the government is supposed to work are only the beginning of the story. The Constitution has been subject to interpretation for the entire history of the United States. Over the past century, Congress has delegated many powers to bureaucracies that are distant from the people and subject to spotty oversight. The Federal Reserve System, created in 1913, is a perfect case in point and has gained such tremendous power that it now almost resembles a fourth branch of government.

Christopher Leonard’s new book, The Lords of Easy Money, documents the increasingly unconventional monetary policy decisions made by the Federal Reserve in the years since the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

One of the Fed’s primary goals, and indeed the reason it was created in the first place, is to promote stability and confidence in the financial system. During periods of crisis, the Fed is expected to step in to ensure that markets continue to function properly. This is supposed to reduce the chances of full-blown financial panics that can result in major economic dislocations harming the real economy.

The Fed’s mandate, updated in 1977 by an act of Congress, is to “promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” The Fed’s historical toolkit to meet these objectives included its control of the money supply and short-term interest rates as well as its regulatory oversight of the banking system.

One of the common arguments put forward by defenders of the Federal Reserve is that its critics advocate a doctrinaire laissez-faire approach in the event of a major economic crisis. Such critics are described as people who deny the complexity of modern industrial economies in an interconnected world and would accept disastrous consequences in exchange for ideological purity.

While it is always possible to identify people willing to make arguments of this sort, the vast majority of Fed critics are not necessarily opposed to strong actions during a crisis. The opposition is more often regarding the failure of the Fed to remove extraordinary policy stances once a crisis has passed. Additionally, many critics focus on the Fed’s oversight role of the banking system and its role in fostering the “too big to fail” (TBTF) problem in which financial institutions grow so important to the economy that they must be bailed out rather than allowed to fail.

The Fed is sometimes portrayed as an intellectual monoculture in which vigorous debate is not tolerated. However, this portrayal obscures a more complex reality as we can see from Mr. Leonard’s reporting in the book. Although he directly interviewed many of the key players within the Federal Reserve, most notably Thomas Hoenig, the book also benefits from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting transcripts which the Fed is required to release with a five year lag. The combination of the meeting transcripts and interviews paints an interesting picture regarding internal dissent behind the scenes.

Thomas M. Hoenig serves as the book’s primary protagonist. He joined the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City in 1973 as an economist charged with banking supervision and served as president of the bank for twenty years ending with his retirement in 2011. Mr. Hoenig was appointed Vice Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in 2012 and served for six years in a role in which he attempted, with little success, to reduce the systemic risk posed by large financial institutions. According to the book’s end notes, Mr. Hoenig was interviewed on numerous occasions between 2016 and 2021 and much of the background regarding the inner workings of the Fed clearly comes from his perspective.

Mr. Hoenig is usually described as an “inflation hawk” or a “dissenter” in the media, but the reality is far more nuanced. As a witness to the great inflation of the 1970s and the resulting fallout that afflicted the banking system throughout the 1980s, Mr. Hoenig’s worldview was shaped by the need to avoid the type of asset bubbles and misallocation of resources that occur at times when inflation gets out of control. During the two decades of his presidency of the Kansas City Fed, Mr. Hoenig cast a total of 67 votes, of which only 12 were dissents. However, eight of those dissents came in 2010, his final year as a voting member of the FOMC. He is tied for fourth place in the number of dissents by FOMC members.

Why did Mr. Hoenig end his career at the Fed with a string of dissents in 2010?

The economy was emerging slowly from the financial crisis with unemployment at stubbornly high levels even with the fed funds rate pegged to zero percent. Despite two years of ultra-low interest rates, consumer price inflation did not appear to be accelerating and Chairman Ben Bernanke felt the need to take even more strenuous actions to spur economic activity.2 His solution was to implement a second round of quantitative easing, a technical term that essentially boils down to printing money and using it to purchase government bonds and other assets. The hope of quantitative easing is that injecting more liquidity into the system will suppress medium-and-longer-term interest rates and encourage capital to be allocated to higher return endeavors that will hopefully create jobs and economic prosperity.

Mr. Leonard presents a comprehensive history of the various rounds of quantitative easing (known as QE1, QE2, and QE3) in the book which I will not describe in detail in this article. The main objection Mr. Hoenig had to the $600 billion second round of QE he voted against in November 2010 was that it would risk creating asset bubbles and impact “allocative efficiency” in the economy. With interest rates pegged at zero percent and new money entering the banking system, there would inevitably be a “reach for yield” in which investors would find all sorts of economic activities acceptable simply because they were better than the zero percent alternative.

Warren Buffett, Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, has compared interest rates to financial gravity. The analogy is particularly apt because every investment decision carries an opportunity cost. If you have the alternative of investing idle cash in a treasury bill yielding 3 percent, you will likely reject many potential business opportunities that you might accept if the treasury bill yields 0.1 percent.

Indeed, this was the explicit goal of quantitative easing, according to Mr. Hoenig and many others cited in the book. The Federal Reserve was purposely attempting to increase asset prices with the hope that the ensuing wealth effect would spur economic growth without triggering consumer price inflation. They were unleashing a flood of newly created money into a system with the risk-free rate at zero knowing that the money would be forced into riskier assets.

If the goal of quantitative easing was to cause asset prices to inflate, the programs were a resounding success. Over the past decade, real estate and stock prices have posted impressive returns as investors desperate for yield turned to riskier and riskier assets. As Mr. Hoenig points out, inflation of asset prices is usually not referred to as “inflation” in the media, but instead lauded as a “boom”.

One inescapable reality of asset price booms is that wealth inequality spikes because individuals of lesser means have few assets to invest in the first place. To make matters worse, rising risk tolerance in such an environment does not necessarily go toward creating real economic value. Rather than focusing on creating value in the real economy, the book documents instances of financial engineering in which corporations use ultra-cheap debt to leverage up balance sheets and wind up creating more fragility. Spiking inequality is often bemoaned by politicians and the media, but the Federal Reserve is not often blamed.

Why does the Federal Reserve see a need to step in and rescue the economy rather than accept that a capitalist economy must include the prospect of both success and failure? The most common answer to this question is that the Fed is tasked with promoting maximum employment by Congress. This is true, and there is no need to suggest that Federal Reserve officials are somehow insensitive to the devastation caused by unemployment. However, the more pressing reason for the Fed to step in to save the system is due to what’s known as the “too big to fail” problem.

The Banking Act of 1933, passed during the depths of the Great Depression, included provisions that came to be known as Glass-Steagall, named after the sponsors of the legislation. Glass-Steagall required the separation of commercial and investment banking. Securities firms and investment banks were not permitted to take deposits from the public and commercial banks were restricted in an attempt to shield them from riskier activities.

The separation of commercial and investment banking was the law of the land until Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999. Following repeal, financial institutions were allowed to encompass both commercial and investment banking activities and they became larger and more interconnected. By 2008, the largest financial institutions had become too big to fail without risking a total collapse of the financial system. This resulted in bailouts of financial institutions justified by the need to save the overall system. Following the financial crisis, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank legislation that was designed to heavily regulate the financial sector which continued to include firms that were unquestionably too big to fail.

In 2012, Thomas Hoenig became Vice Chairman of the FDIC after retiring from the Kansas City Federal Reserve. Mr. Hoenig’s view was that the highly intricate web of regulations was unlikely to work during times of crisis. Despite a “stress testing” regime imposed by the Dodd-Frank legislation, measuring regulatory capital levels and assessing true risk in a crisis was not something Mr. Hoenig thought could be distilled down to economic models. Instead, he advocated returning to the separation of commercial and investment banking and exerting a lighter regulatory posture once institutions were no longer large enough to cause systemic risk. Such smaller institutions could be allowed to fail in an orderly manner without the risk of bringing down the entire financial system.

Despite the fact that both major parties supported reinstating Glass-Steagall during the 2016 election, this did not occur. Mr. Hoenig is quoted in the book commenting on how he would exit a lawmaker’s office after discussing his proposals only to see bank lobbyists he knew enter the office. The writing was on the wall. Mr. Hoenig was passed over for Chairman of the FDIC and left government service in 2018.

From the perspective of early 2022, Mr. Hoenig seems like a prophet, but in reality, he was one of many voices warning about the systemic risks building in the economy due to the Fed’s ultra-loose policy decisions since 2008. As the book makes clear, there were other dissenting voices within the Fed during the crucial period during which QE2 was debated in 2010, but everyone but Mr. Hoenig wound up voting in favor of Ben Bernanke’s proposal. Mr. Hoenig stood alone in terms of the courage to act on his convictions.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has signaled the Fed’s intention to raise the federal funds rate from near zero and to begin the process of reversing quantitative easing later this year. However, the FOMC took no such actions at its January 2022 meeting leading observers to conclude that the tightening process would commence in March. There is currently heated debate regarding the cause of consumer price inflation that is currently running at 7 percent. For months, Chairman Powell insisted that inflation was “transitory” and would subside once temporary supply disruptions related to the pandemic abate.

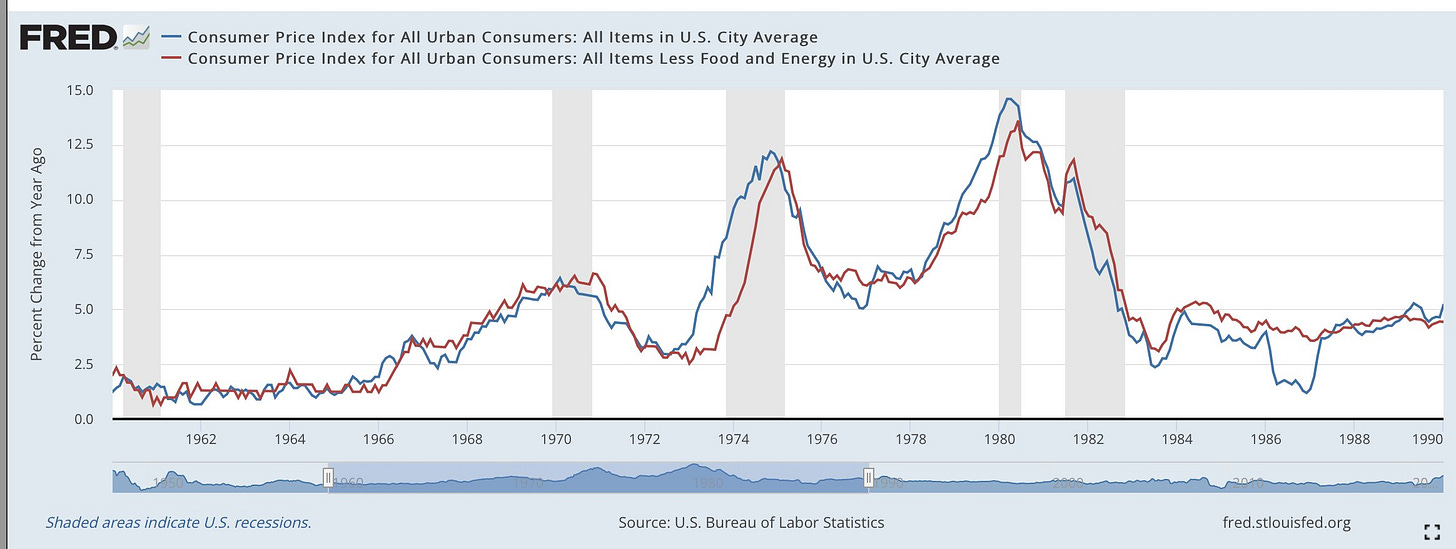

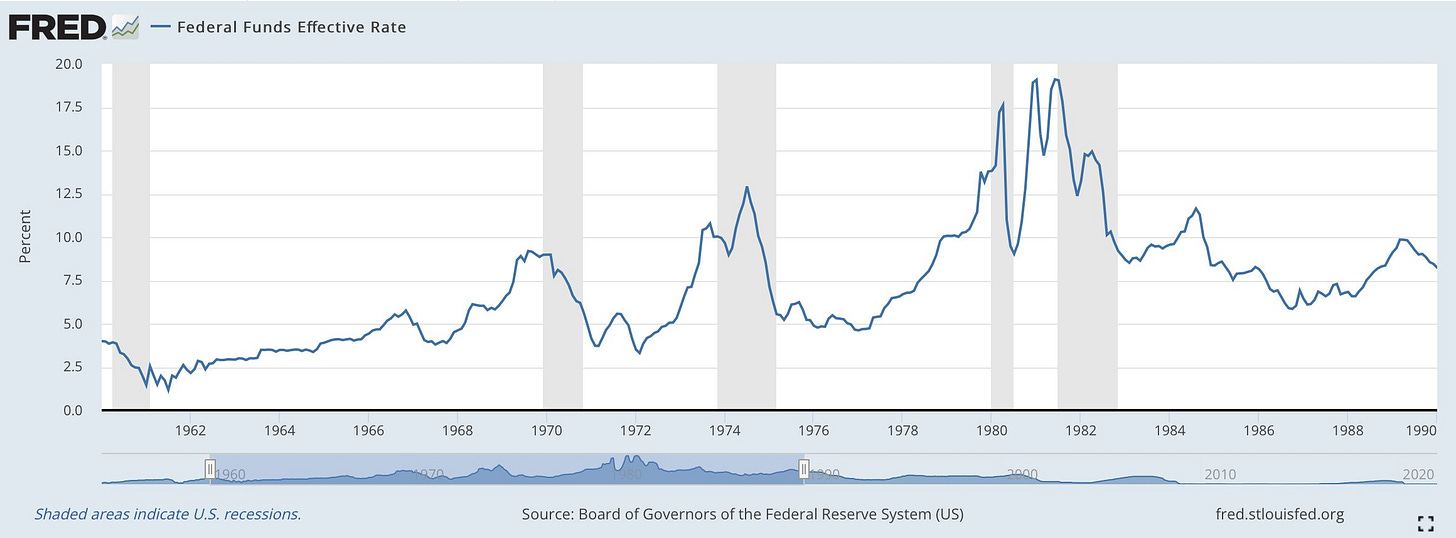

The truth is that no one knows what the course of inflation will be over the next year, but one thing we do know is that the federal funds rate has never been lower at a time of high single digit inflation in the consumer price index. The following charts show the level of the fed funds rate and inflation for the thirty-year period ending in 1990 which includes the last major inflationary period in the United States:

Obviously, the United States economy is far different today than it was during the 1960-1990 timeframe, but the charts are nonetheless sobering. We have never embarked on a period of high single digit inflation with the federal funds rate anywhere near zero. Additionally, we have never entered such a period after a massive spree of money creation with plans to begin draining trillions of dollars of liquidity from the system.

Mr. Leonard documents what happened when the Federal Reserve briefly attempted to reverse quantitative easing in 2018 and 2019. This attempted tightening ended amid market volatility in early 2019 and the Fed effectively began quantitative easing again in September 2019 after serious disruptions in money markets. Quantitative easing accelerated rapidly once the pandemic began in early 2020 and continues to this day. Whether the Fed will be able to actually end quantitative easing and begin quantitative tightening is an open question.

I will conclude this article with the following quote from an article published by the St. Louis Fed in 2013. Based on the Federal Reserve’s own definition, failure to implement quantitative tightening to reduce the size of the balance sheet will represent monetization of government debt. As we can see from the chart provided below the quote, the prospect of removing the trillions of dollars of money creation since the 2008 financial crisis is daunting.

“If the recent rapid accumulation of Treasury debt on the Fed’s balance sheet constitutes a permanent acquisition, then the corresponding supply of new money would be expected to remain in the economy (as either cash in circulation or bank reserves) permanently as well. As the interest earned on securities held by the Fed is remitted to the Treasury, the government essentially can borrow and spend this money for free.

If, on the other hand, the recent increase in Fed Treasury debt holdings is only temporary (an unusually large acquisition in response to an unusually large recession), then the public must expect that the monetary base at some point will return to a more normal level (through sales of securities or by letting the securities mature without replacing them). Under this latter scenario, the Fed is not monetizing government debt—it is simply managing the supply of the monetary base in accordance with the goals set by its dual mandate.”

Is The Fed Monetizing Government Debt? (St Louis Fed, 2013)

I am among the skeptics regarding whether the balance sheet will ever be reduced materially. The effect on permanent inflation of consumer prices and asset prices is yet to be determined, but my view is that the final bill has not yet arrived and that the damage will be significant. Only time will tell.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

The Lords of Easy Money, p. 219

The most commonly reported measure of inflation is the consumer price index (CPI) which is measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a division of the executive branch of the federal government. There are long-running disputes regarding whether the CPI accurately measures the cost of living and the components and methodology of the CPI has changed over time. I do not enter into the debate over the accuracy of the CPI in this article but wish to note that the claim that consumer inflation was subdued during the 2010s is not without controversy.