The smartphone has increased the number of words the typical person reads on a daily basis more than any invention in history.

All of a sudden, millions of people started carrying a pocket-sized supercomputer everywhere and the amount of content available to read skyrocketed. Everyone is glued to their screens constantly. If you doubt this, leave your phone at home, walk to the nearest cafe, sit down, and just observe people for an hour or two.

But exactly what is everyone reading?

For the most part, people are reading content that was created very recently, most likely within the past few hours. This is true whether the content is in the form of an email, text message, social media post, or click-bait article that has gone viral.

We are constantly focused on what is happening right now and the reading that we are doing is in tiny, bite-sized pieces that can be consumed in seconds or minutes. On social media, our attention flits from one tiny piece of bite-sized content to the next, interrupted only by coming up with our own clever response which, in turn, will generate more bite-sized replies, most of which will be useless nonsense.

We are reading more words every year, but these words tend to be vapid nuggets that will become obsolete moments after we read them. There is no meat on the bones of what most people read today. It’s like consuming a perennial diet of sugar-laden breakfast cereal followed by an ice cream sundae.

Junk food.

Now that we are a few hundred words into this essay, I know that I am probably preaching to the choir. You already realize that the “content” most people read is junk food and you already make an effort to read longer-form articles and actual books. My guess is that most of you read several books every year. I do not need to “sell” you on the value of reading books. You already understand the value of doing so.

But what kind of books should we focus on?

This is a difficult question to answer. A quick glance through the book reviews I have published on The Rational Walk makes it clear that I have favored books that were published over the past half century. In many cases, I have reviewed books that are brand new. While I do not review every book that I read, it is fair to say that I have focused on contemporary reading over the past two decades.

Does it make sense to favor recent books?

One can argue that doing so allows us to remain abreast of developments that are currently underway at a deeper level than what is available in bite-sized format on social media. It is obviously better to read Walter Isaacson’s recent biography of Elon Musk than to form your opinion of the man through social media posts. The same is true when it comes to understanding technology, business, and politics.

But we are missing something important.

Nassim Taleb’s concept of the Lindy Effect asserts that the expected lifespan of a non-perishable thing is proportional to its current age. In other words, if a book has remained in print for fifty years, it is a good bet that it will still be in print and widely read in another fifty years. Most books that are published today will have fleeting lives because they will fail to maintain any sort of relevancy a few short years from now.

This does not mean that we should ignore recent books if there is immediate utility associated with reading them. But we should not confuse that type of reading with gaining the sort of worldly wisdom that Berkshire Hathaway Vice Chairman Charlie Munger has long advocated. Mr. Munger reads several newspapers every day, but he is also known to have a large personal library and reads voraciously.

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people (over a broad subject matter area) who didn’t read all the time — none, zero. You’d be amazed at how much Warren [Buffett] reads–and at how much I read. My children laugh at me. They think I’m a book with a couple of legs sticking out.”

— Charlie Munger, Poor Charlie’s Almanack

One of Mr. Munger’s interests is to gain a more comprehensive understanding of human psychology. Despite having no academic training in the field, Mr. Munger has developed a psychology of human misjudgment based on the combination of reading and observing human beings over a very long life.

Human nature resists fundamental change.

It is hard to believe that people who lived decades or centuries ago could possibly share much in common with us today given how technology has altered society. However, human nature and psychology is remarkably constant. What we consider to be “long” periods of time are actually just tiny moments in our evolutionary history.

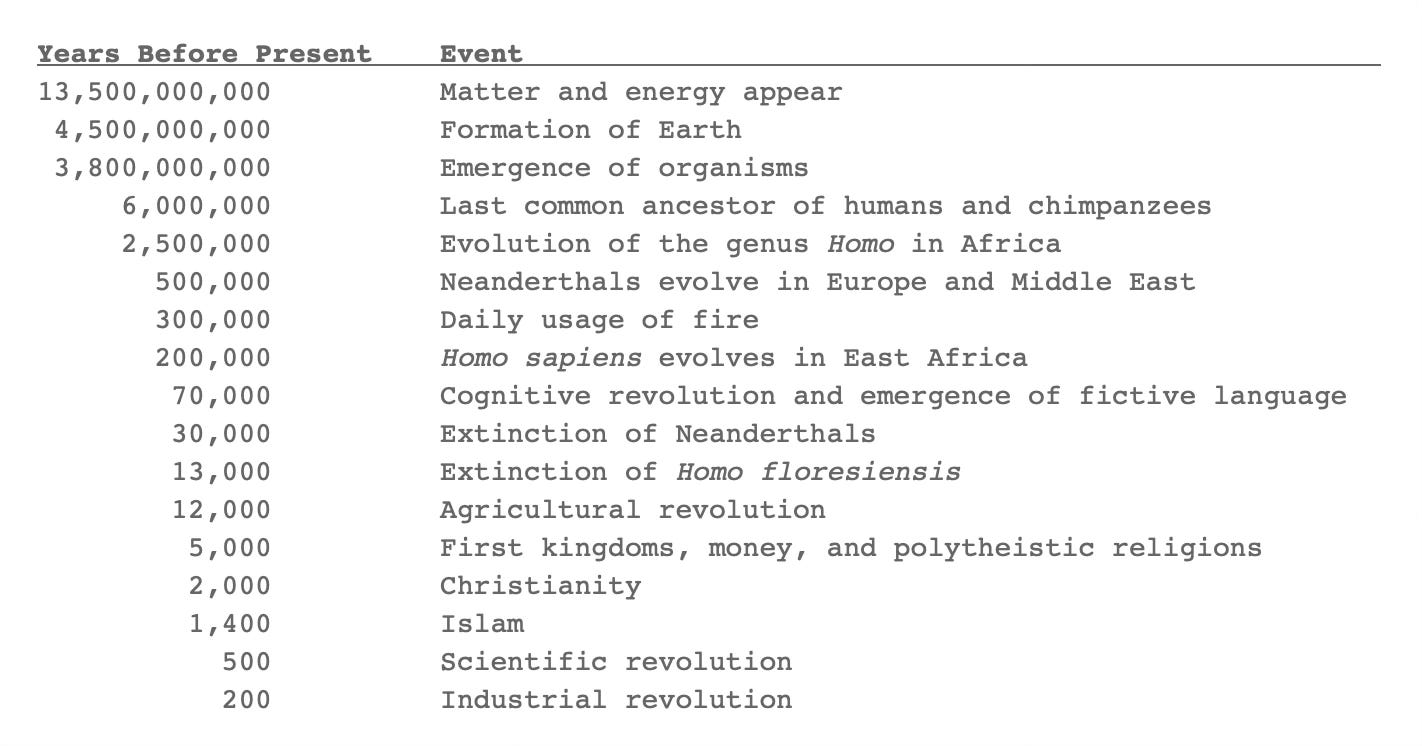

Consider the following table that I created based on the timeline presented by Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind:

In the context of evolution, what we think of as recorded history is almost nothing. Why should it surprise us that we might share much in common with those who lived during the time of the Roman Empire, the Renaissance, the Revolutionary War, or the Great Depression? All of these events took place very recently!

Still, the idea that we share much in common with those who lived a couple thousand years ago is intuitively absurd since our civilization has advanced so radically. The same is true when we think about how our great-grandparents lived.

In other words, if you’re going to suggest that human nature has not changed in thousands of years, you need to prove it!

Well, how can we possibly prove it? We do not have photographs, videos, or even voice recordings of those who lived hundreds of years ago. We cannot get a sense of what they were like by watching a clip on social media. They seem impossibly remote.

The only way we can seek proof is to read the words of those who lived long ago. When we do so, we start to get a sense of the travails of day-to-day life and gain an appreciation of the nature of people who are long dead. Did these people commit the same sins? Were they envious, greedy, lustful, and often murderous? Did they engage in the same petty, vindictive feuds? Or were they somehow above our current follies?

Passive reading is better than nothing but active reading is far better. Mortimer Adler’s How to Read a Book provides much guidance on how we should make reading an active pursuit by, in a sense, having a “conversation” with the author:

“There are two ways in which one can own a book. The first is the property right you establish by paying for it, just as you pay for clothes and furniture. But this act of purchase is only the prelude to possession. Full ownership comes only when you have made it a part of yourself, and the best way to make yourself a part of it is by writing in it. An illustration may make the point clear. You buy a beefsteak and transfer it from the butcher’s icebox to your own. But you do not own the beefsteak in the most important sense until you consume it and get it into your bloodstream. I am arguing that books, too, must be absorbed in your blood stream to do you any good.”

Unlike videos and other forms of ephemeral content, a book is something can be read at your own pace. You can pause after reading a section, think about what you just read, and mark up the book with your highlights and comments. You can read it again, as many times as you see fit. You can discuss the book with others who have read it. And when the book in question is one that has passed the “Lindy” test of existing for decades or, better yet, centuries, chances are very good that others like you have come up with similar dialogs with the author in the past.

Like many people, I was exposed to several of the Great Books of Western Civilization as a student but I lacked the life experience and motivation to get much out of what I read. Still, this experience was valuable because some remnant of what I had read remained. In recent years, I have revisited many of the books but I made the error of not reading them actively. I read the contents but did not have a “conversation” with the author. As a result, I did not take full ownership of the contents.

I’ve recently started to re-read Montaigne’s Essays and I am currently reading St. Augustine’s Confessions for the first time. What’s interesting is that I have much in common, in terms of underlying human psychology, with these men who lived centuries apart and who also shared much in common with each other. By marking up the books and keeping a commonplace journal, I’m having a two-way conversation with men long dead and taking the lessons they tried to teach into my “bloodstream.”

Why dedicate most of my reading time to the Great Books?

I have been an avid reader for over fifteen years, but most of the books I have read were published within the last fifty years. Much of the wisdom of the world was written down long before the mid to late twentieth century. I plan to write articles and essays, such as this one, about the books I am reading. In addition, I will record some informal thoughts in the form of public notebook entries.

You should be aware that this effort is a selfish endeavor.

I am writing in public because I have found that doing so forces me to clarify my own thinking. By explaining concepts and ideas to others, I must truly understand what I am writing about or risk looking foolish. Writing privately is good, but trying to explain something to others is better. Of course, I hope that what I write proves to be interesting to others, but that is a secondary objective.

My plan is to publish general articles on my reading journey, such as this one.

I will also try out the concept of writing informal notebook entries in public.

How many of the books will I read?

The truth is that I do not know what the future holds. However, I am planning to shift the focus of my reading to books that have endured for very long periods of time. If I have good health for my remaining life expectancy, I should be able to read well over a thousand books of average length and I intend to make each of them count.

Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.