“News, to put it simply, is what people don’t know that they want to know. And people will seek their news – what’s important to them – from whatever sources provide the best combination of immediacy, ease of access, reliability, comprehensiveness and low cost.”

— Warren Buffett, 2012 Annual Letter to Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders

Human beings have an innate curiosity and desire to know what is happening in the wider world beyond their immediate circle of family, friends, neighbors, and co-workers. In peaceful and prosperous societies, the type of information most people seek might be mundane details about a vote in the city council, the fortunes of the local high school football team, job openings at the new factory, what’s on sale at the supermarket, or the weather forecast for their picnic on Saturday. In times of crisis, we have a desperate need to know the current state of affairs in order to take action ourselves or just to understand what is happening around us.

From the end of the Second World War until almost the end of the twentieth century, almost all Americans got this type of information from one of three sources: television, radio, and the local newspaper. Events of the day were curated by professional journalists who, for the most part, attempted to report the news accurately. The news was disseminated by large organizations that, while not without occasional controversy, were mostly trusted by the majority of people. Some of my earliest memories as a child include the evening ritual of my parents turning on the television to watch Walter Cronkite provide his summary of the news. In the morning, I would hear the familiar CBS Radio chime and know it was the top of the hour. As a teenager, I delivered the local newspaper starting with the afternoon edition and later moving to a larger morning route. Serious people took the news very seriously.

Then the internet changed everything.

Suddenly, in the final years of the twentieth century, anyone with a computer and an internet connection had an unlimited supply of news provided first by hundreds and soon by thousands of publishers. Not only did we have access to newspapers from around the world but we gained access to less formal sources of information written by ordinary people. For the most part, this information was not only abundant but was also free. Within the span of a few years, the comfortable culture of journalism was completely upended, never to be the same again.

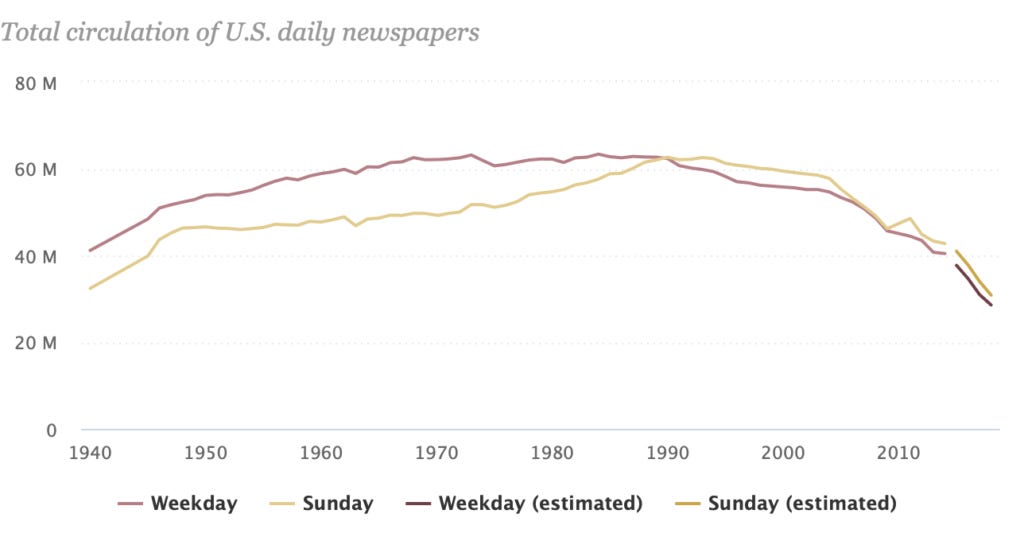

The massive upside of diversity of sources, freedom of speech, and lower economic costs were initially all that we focused on but it slowly became apparent that something has been lost as well. Whereas society previously relied on journalists to decide what constituted information as opposed to mere noise, we now must take much more responsibility for differentiating between the signal and noise for ourselves. Journalism became too insular and comfortable and did not react quickly enough to make the case for its crucial role in a free society. With few exceptions, newspapers have been unable to charge customers for content online and total circulation (print and digital) has fallen precipitously to levels not seen since before 1940 when the U.S. population was less than half of today’s level.

Not surprisingly, the drop in circulation has been accompanied by a precipitous decline in advertising revenue for almost all newspaper publishers. According to the Pew Research Center, U.S. newspaper advertising revenue peaked at $49.4 billion in 2005 and dropped to $14.3 billion by 2018. The decline in circulation revenue has been less severe, peaking at $11.2 billion in 2003 and coming in at just under $11 billion in 2018. In inflation adjusted terms, of course, the circulation revenue decline has been more significant.

Newspapers face a vicious cycle: As circulation declines, they must increase the price of papers to customers to maintain circulation revenue, but the subsequent decline in readership dissuades more advertisers who gain access to fewer and fewer eyeballs every year.

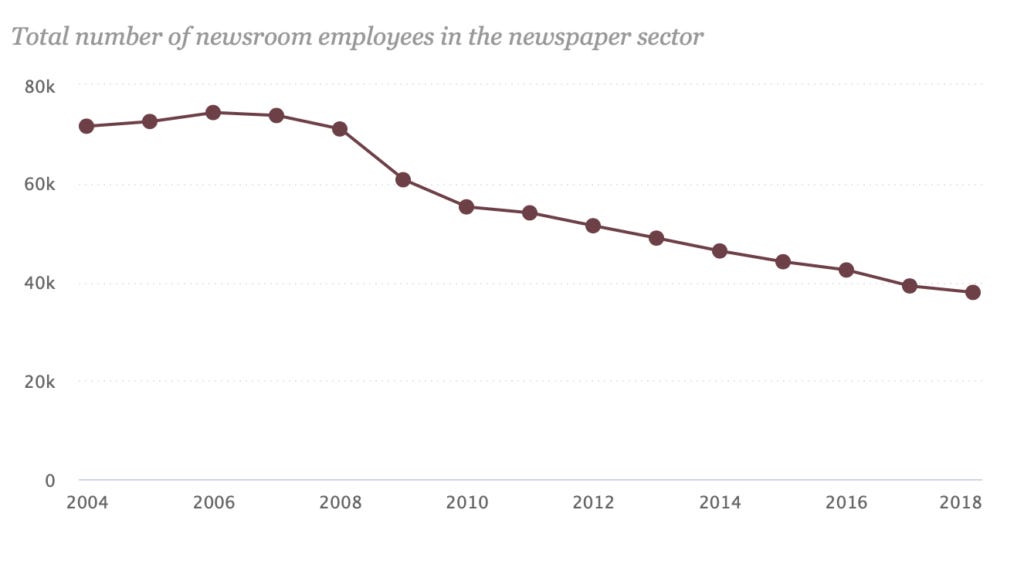

Not surprisingly, newspapers have made major cuts to newsroom staff over the past twenty years.

Cutting investment in staffing inevitably results in degradation of the content needed to attract readers. Newspapers then must decide whether to attempt to maintain circulation revenue by raising prices for die-hard readers, who might be on the older side and continue subscribing simply by force of habit, but at the cost of losing less committed readers. Then as circulation counts drop again, advertisers will cut their orders since fewer eyeballs will see their promotions, and the vicious cycle continues.

A Man of Unlimited Confidence

The cacophony of views prevalent on the internet today has no equal in human history, but there was a time when traditional print newspapers were far more numerous and competitive. From Butler to Buffett: The Story Behind the Buffalo News provides a great example of the evolution of newspapers from the late nineteenth century up through the consolidation of the industry that was largely complete a hundred years later.

Murray B. Light, who worked for the Buffalo News for a half century starting in 1949, provides a fascinating account of how the paper transformed from a scrappy startup founded by Edward Butler in 1873 into the only surviving newspaper in the city 110 years later. Light, who passed away in 2011, was asked to write a history of the newspaper by Warren Buffett who had purchased the Buffalo News in 1977. The book is both a history of the newspaper as well as the personal memoir of a longtime veteran of twentieth century journalism.

When Edward H. Butler arrived in Buffalo in 1873, he saw an opportunity. Although the city had ten newspapers, none of them published a Sunday edition. This might seem odd in light of the much expanded Sunday newspapers that seemed to grow larger and larger during the twentieth century. Obviously, people would have more time to read on weekends. But 1870s Buffalo was a weird mix of vice — there were nearly a hundred saloons, numerous gambling parlors, and plentiful houses of ill repute — and virtue, with religious ministers united in saying that any commercial activity, including newspaper publication, on Sundays would degrade the sanctity of the Sabbath.

Butler, who was only 23 years old at the time of his arrival in the city, plowed ahead anyway. He firmly believed that any enterprise would succeed under his leadership. He was a man of unlimited confidence. So on December 7, 1873, the first issue of the Buffalo Sunday News was published despite the vociferous opposition. Unlike most the newspapers of his era, Butler took a non-partisan position. He was determined to not serve as a political party organ and he wanted to provide information relevant to everyone in the family. Butler’s strategy was immediately successful with rapid gains in circulation which brought about a virtuous cycle that would attract more advertisers, and in turn even more readers. Although Butler did not take an overtly political posture, his affiliation with the progressive politics of the era caused the paper to pay special attention to the plight of the poor at a time when few labor protections were enshrined into law.

By 1880, several competing newspapers had started Sunday editions and Butler decided to aggressively move into the market for daily newspapers. Employing a bold strategy, Butler rolled out his daily evening newspaper, named The Buffalo Evening News, at a bargain price of one cent per copy at a time when competitors were charging five cents. This highly promotional pricing attracted readers and the readers attracted advertisers — the classic economic model for newspapers that would last for another century. Butler was a man of seemingly unlimited energy who was involved in every facet of the enterprise until his death in 1914. By 1897, his paper claimed to have a larger circulation than the combined circulation of all competing Buffalo daily papers. Although this claim was somewhat dubious, Butler did have nearly twice as much circulation as his nearest competitor and dominated the field.

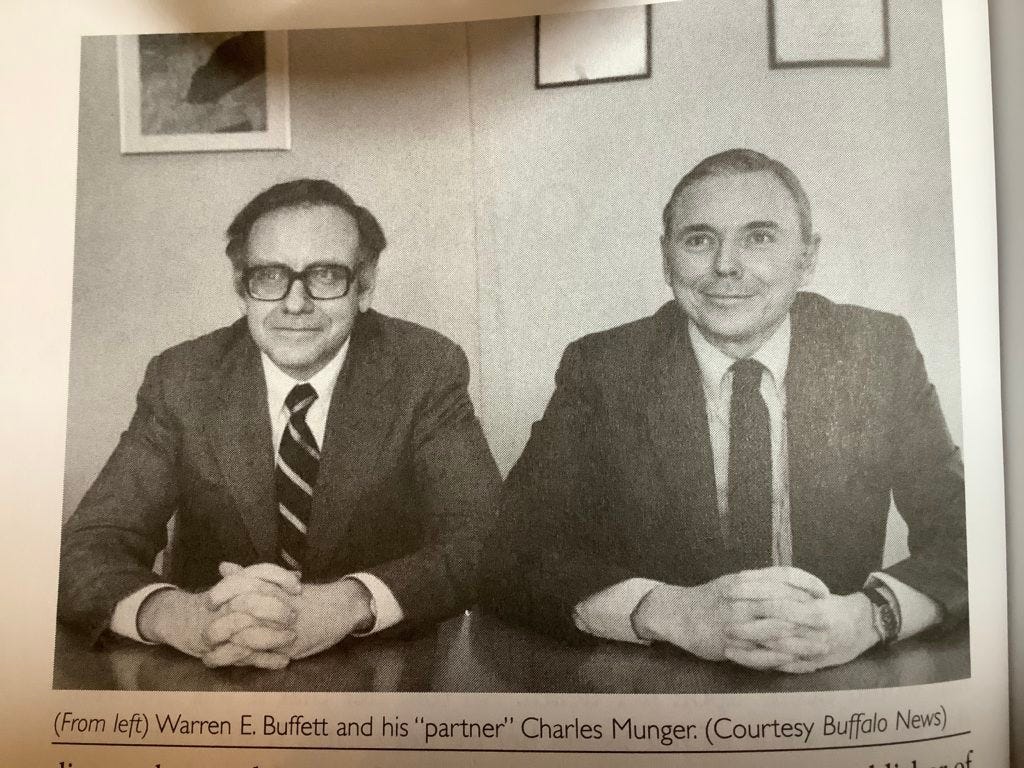

During the final decade of his life, Butler became more involved in politics and, in 1912, he turned over management of the paper to his son, Edward H. Butler Jr., who would run the newspaper until his death in 1956. The Buffalo News would remain in the hands of family members until Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger purchased the paper in 1977. Murray Light entered the scene in 1949 as a young copyeditor and, from that point forward in the chronology, the story benefits from his own eyewitness account of major developments within the company and the city of Buffalo.

Although the early history of Butler’s founding of the newspaper is fascinating and should hold any reader’s interest, Light’s later description of the many characters who shaped the paper from the 1950s into the 1990s is likely to be of more interest to a reader who is specifically interested in the individuals involved. Much of the narrative involves what could be thought of as “inside baseball” — stories of newspapermen who were “characters”, politics within the organization, and the many promotions and controversies that exist within any large organization.

Enter Buffett and Munger

After remaining in family control for over a hundred years, the estate tax finally compelled the Butlers to put the newspaper on the market following the death of Kate Butler in August 1974. Kate Butler had taken over management of the newspaper in 1956 when her husband, Edward H. Butler Jr., passed away and she stubbornly refused to transfer control of her interest in the paper prior to her death. Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger enter the narrative almost exactly halfway into the book where Light provides a summary of the steps the family took to sell the paper and how it came to be purchased by Blue Chip Stamps on April 15, 1977 for $35,509,000.

Blue Chip Stamps was one of the corporate entities that was partially owned by Berkshire Hathaway during its early years. Charlie Munger served as Chairman of Blue Chip Stamps, but both he and Buffett were actively involved in the decision to purchase The Buffalo News and had a role in dealing with the difficult early years of their ownership. Although Light does tell the familiar story of Berkshire’s troubles with the newspaper during the early years, a reader who is more interested in the specifics of the story would be well served to read Charlie Munger’s letters to Blue Chip shareholders that have been helpfully compiled by Max Olson.

Although Butler started out in Buffalo with a Sunday only publication and only later moved to daily publication, his successor decided to eliminate the Sunday issue in 1915. By the time Buffett and Munger took control, The Buffalo News had lacked a Sunday offering for over sixty years. Instead of a Sunday edition, The Buffalo News published an expanded Saturday “weekend” edition but this was a poor substitute for readers with leisure time available on Sunday mornings who did not want to read stale news. By 1977, Buffalo was a city with two newspapers — The Buffalo News which published in the afternoons from Monday to Friday as well as its Saturday weekend edition and The Buffalo Courier-Express which published a morning edition seven days a week. Buffett and Munger were convinced that to remain relevant, their newspaper had to publish seven days per week.

Warren Buffett is well known for his love of newspapers and he obviously took great pleasure in helping craft the advertising and circulation pricing strategy prior to the rollout of the Sunday paper. At the same time, Light says that Buffett took an entirely hands-off approach when it came to setting newspaper editorial policy. As Buffett wrote to a friend at the time, he was “having so much fun with this it is sinful.”

Publication of the first Sunday issue was set for November 13, 1977, but two weeks before launch, the Courier-Express filed an anti-trust lawsuit alleging that The Buffalo News was using its strong position during the week to subsidize a loss making paper on Sunday, with the intent of eventually driving The Courier-Express out of business. The Courier-Express was fortunate to find a friendly judge who imposed onerous conditions on the rollout of Sunday paper and this caused several years of struggles for The Buffalo News before an appeals court rejected the lower court’s findings. However, the troubled early years were not over for Buffett and Munger. They faced a strike in 1980 and an additional three years of heavy losses until The Courier-Express finally ceased publication in the fall of 1982. At that point, The Buffalo News started a morning edition and Buffalo became a one newspaper town.

It is doubtful that Buffett and Munger in any way expected the kind of turmoil they faced immediately after purchasing the newspaper. For several years, Charlie Munger warned Blue Chip shareholders that The Buffalo News could be forced to cease publication and liquidate if the legal situation did not improve and labor relations worsened. Even in his valedictory letter to shareholders in early 1983, on the eve of Berkshire acquiring full ownership of Blue Chip, Munger characteristically refuses to brag about the turnaround that was already underway and states that he and Buffett might just have been lucky:

Finally, our shareholders should recognize that if our 1977 purchase of the News has now worked out acceptably from their viewpoint, which contrary to our prediction last year may now be true even after taking into account time delays, the conclusion does not follow that we made a sound managerial decision buying the News when we did for the price we paid. In retrospect, we were strongly influenced because we liked the newspaper, its people and the city, and we may simply have gambled shareholders’ money against the odds and won. Our stewardship may have been, at best, dubious in this instance. We know that the financial outcome we now report could with slightly different breaks just as well have been either (1) a large loss on closure of the News or (2) the expectation of much more money-losing in continued operation, as part of the only defensive strategy with reasonable prospects.

CHARLIE MUNGER’S 1982 LETTER TO BLUE CHIP STAMPS SHAREHOLDERS

Charlie Munger was being modest. From 1983 through the end of the century, when Berkshire stopped breaking out reporting for the newspaper in its annual reports, the business provided consistently excellent results when viewed in light of the initial acquisition cost:

Nothing Lasts Forever

Berkshire continued to own The Buffalo News for another two decades after the newspaper became too small for the growing conglomerate to break down its results in a granular manner. Buffett and Munger, although fully aware of the internet and the changing competitive landscape, never ceased to love the newspaper business, perhaps due to the wonderful economics that The Buffalo News eventually produced along with Berkshire’s experience owning shares of The Washington Post. During the early 2010s, Berkshire began purchasing additional newspapers at distressed prices, as Buffett discussed at length in his 2012 annual letter. His hope was that the acquisitions were made at prices that fully reflected the inevitable continued decline that he regarded as inevitable.

From 2012 to 2017, Berkshire reported circulation figures for its newspaper properties, and the tabulation of this data confirms the decline. During this period, The Buffalo News saw its daily circulation drop by nearly 27 percent. The table below is a compilation of circulation data taken from Berkshire’s annual reports before the presentation was discontinued in the 2018 annual report:

Finally, in January 2020, Berkshire announced that its newspaper holdings would be sold to Lee Enterprises for $140 million, marking a rare instance where Warren Buffett has sold businesses within the Berkshire conglomerate. Lee had previously taken over management of Berkshire’s newspapers in 2018 with the exception of The Buffalo News. However, The Buffalo News was included in the sale to Lee which closed in March. Berkshire continues to have an interest in the success of the newspapers having extended Lee $576 million of long-term financing at an interest rate of 9 percent.

Taking the long view, it is clear that Berkshire Hathaway is far better off because Buffett and Munger saw the enviable economics of the newspaper industry back in the 1970s and decided to get involved in a big way, both directly via The Buffalo News and indirectly as a longtime shareholder of The Washington Post. This early positive experience clearly influenced Buffett’s decision to purchase his collection of papers in the 2010s, but these purchases were made at distressed prices that discounted continued decline. However, the decline obviously proceeded faster than Buffett anticipated and the media group might have become a distraction. Berkshire has not so much exited the newspaper industry as exchanged its equity ownership position for high yielding debt in the form of financing to Lee. Time will tell whether this commitment works out for Berkshire shareholders in the long run.

Murray Light clearly loved The Buffalo News and spent his entire professional career at the newspaper. The rough and tumble of the internet in the 21st century makes the world Light inhabited seem almost foreign in comparison. We should not necessarily wish for a return to those times. The concentrated nature of news delivery in the twentieth century provided the impression of greater stability, but only because fewer voices were being heard.

The chaos of the internet in the 2020s produces tremendous noise but also an unlimited variety of perspectives. However, it is our jobs as consumers of the news to separate the wheat from the chaff. And lately, it seems like there has been an abundance of chaff and little wheat when it comes to feeding our daily need for information.

Disclosure: Individuals associated with The Rational Walk LLC own shares of Berkshire Hathaway.