Tax The Small Investor Behind The Tree

“Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax that fellow behind the tree!”

“Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax that fellow behind the tree!”

“No one should see how laws or sausages are made. To retain respect for sausages and laws, one must not watch them in the making. The making of laws like the making of sausages, is not a pretty sight.”

— Source uncertain but often attributed to Otto von Bismarck

As much as value focused investors might prefer to be reading annual reports and conducting other fundamental research, it has been difficult in recent months to ignore the various permutations of “tax reform” that have been taking shape in Washington. Even Warren Buffett, someone who is known for his aversion to political distractions, has admitted that tax reform is a big factor in his decision making this year.

After failing to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, Republican politicians are desperate to deliver on at least some of their campaign promises. The House of Representatives has already passed tax reform legislation and the Senate is very close to voting on their own tax package. Assuming passage of a tax bill in the Senate, the House and Senate will enter reconciliation discussions before attempting to pass a final bill that the President will sign into law. The goal is for legislation to be signed into law by the end of the year.

While there are many aspects of tax reform that will have major impacts on business conditions and the investment climate, one specific proposal has made its way into Senate legislation that appears to specifically target individual investors. The change has to do with how investors calculate the cost basis of shares at the time shares are sold. Currently, investors are able to specify the specific shares that are being sold which makes it possible to minimize capital gains taxes when part of a position is being sold. Under the Senate proposal, investors would have to dispose of shares on a “first-in-first-out”, or FIFO, basis.

Obscure Accounting –> Real Life Impacts

This change might seem technical and obscure but it has powerful real impacts on small investors who have steadily purchased shares of companies over long periods of time. In contrast, it has virtually no impact on traders who turn over their portfolios several times per year.

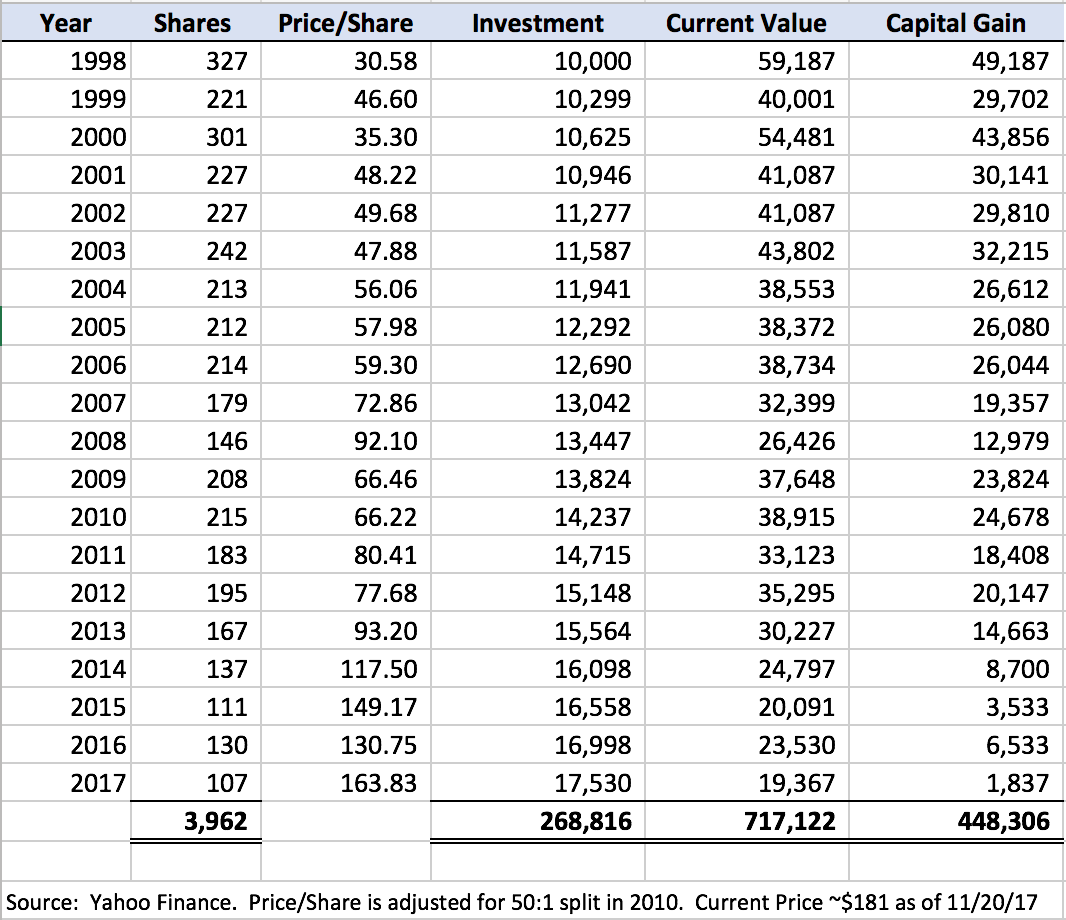

Let’s take a look at a hypothetical example that demonstrates the real life impact of the Senate’s proposal on a small investor. James is a 65 year old pharmacist who plans to retire on January 1, 2018. Over the past twenty years, James has invested in Berkshire Hathaway B shares on the first trading day of each year. He started in 1998 with a $10,000 investment that purchased 327 Berkshire Hathaway B shares (split adjusted – assume for this example that purchasing fractional pre-split shares would have been possible). Every year, he increased his investment by approximately 3 percent which roughly mirrored increases in his paycheck. Today he owns 3,962 shares of Berkshire Class B worth slightly more than $717,000. Of this amount, over $448,000 represents capital gains. The exhibit below illustrates the annual purchases and the capital gain attributed to each purchase:

So the time has come for James to retire and he plans to draw down his portfolio of Berkshire shares at a rate of 4 percent per year to fund part of his retirement expenses. This drawdown will start on the first trading day of 2018 and will involve a sale of 158 shares. If Berkshire’s class B shares are trading at around today’s level of $181 at the beginning of 2018, the sale of 158 shares will result in proceeds of roughly $28,600. (For purposes of this discussion, we will ignore commissions which are so low these days as to be nearly immaterial).

James has always expected to pay capital gains taxes when he started selling shares in retirement. However, his accumulation of shares over the years was based on the understanding that he would be able to select the specific shares that were being sold. Under current law prevailing in 2017, he would select the entire 2017 lot of 107 shares as well as 51 shares out of the 2015 lot of shares. Here is what the capital gain would be under current law:

2017 Lot: 107 shares sold at $181 (basis: $163.83) for proceeds of $19,367 with a gain of $1,837.

2015 Lot: 51 shares sold at $181 (basis: $149.17) for proceeds of $9,231 with a gain of $1,623.

Total Proceeds: 158 shares sold at $181 for proceeds of $28,598.

Total Capital Gain: $3,460

Under the Senate proposal, James would not have the ability to specify the shares that he is selling. The assumption would be that the 158 shares being sold are from his first tax lot, that is, the shares that he purchased back at the beginning of 1998. So, under the proposed law, here is what the capital gain would look like:

1998 Lot: 158 shares sold at $181 (basis: $30.58) for proceeds of $28,598 with a gain of $23,766.

Assuming that James is in the 25 percent tax bracket for ordinary income, he would pay Federal capital gains taxes at the 15 percent rate:

Federal tax due under current law: 0.15 x 3,460 = $519

Federal tax due under proposed law: 0.15 x 23,766 = $3,565

Granted, it is true that James may benefit from other aspects of the tax reform legislation that could blunt the impact of this increase in capital gains taxes, but it would take a significant offset elsewhere to recover from a ~$3,000 capital gains tax hike due to the Senate’s tax proposal. On capital gains, at least, James feels somewhat like Charlie Brown when Lucy pulls away the football. His careful strategy of accumulating shares over two decades and intent to liquidate the highest cost basis shares first has been thwarted by an obscure provision motivated primarily by Senators desperately trying to get the bill to “score” more favorably. The change is intended to raise revenue. When Fidelity, Vanguard and other mutual fund firms objected, the Senators answered the phone and exempted fund companies. Will they even answer a call from James?

Broader Effects

The impact on individual investors facing near term tax hikes should be clear but there are also broader effects that may or may not have been discussed by the politicians. One clear impact will involve estate planning. Shares that are left to heirs receive a “step-up” in cost basis coinciding with the date of death. In other words, when James passes away, his low cost basis shares will “step up” to the current stock price so that his heirs will only owe capital gains taxes on further appreciation. By being forced to liquidate lower cost basis shares, James will be less able to pass on low cost basis shares to his heirs.

The proposed change will also impact investors still in their accumulating years. Let’s say that James is not retiring next year but in ten years. Will he still want to put new savings each year into Berkshire Class B shares knowing that these specific shares cannot be “sold” under all of the lower cost basis shares in his portfolio are disposed of? Effectively, recent lots of stock are “trapped” in the sense that they can only be liquidated after all of the earlier shares are sold. James might well decide to put his funds into another company instead knowing that he can liquidate those shares at a relatively high cost basis, if desired. Some might say he should be diversifying anyway, but isn’t that a decision that should be made based on the merits of investment choices and an individual’s personal view of the best place to invest his or her funds?

Any tax policy that causes investors to depart from acting based on fundamentals is bound to cause inefficiency in allocation of capital. At the micro level, as with James, this has no discernible macroeconomic impact. But when millions of potentially suboptimal tax driven decisions are aggregated, it could well have an impact on how capital is allocated economy-wide.

Tax reform was supposed to simplify the overall system, raise the funds necessary to run the government, and allow decision making to be based on business merits rather than playing tax games. While there is always going to be a certain amount of lobbying and sausage making in Washington, it is disappointing that a supposedly “pro-business” party has presided over reform proposals that not only fail to achieve the stated objectives but might actually further distort economic incentives and decision making.

UPDATE: The final tax legislation passed by Congress in late December 2017 did not include the FIFO changes discussed in this article. However, it is quite possible that this provision could be included in future tax law changes now that it has been brought up as a revenue raising idea.