Measuring Competence

Measuring competence is straight forward in many fields, such as carpentry and dentistry, but not as clear when it comes to investing.

I have moved ten times over the past four decades. Only one piece of furniture has survived.

It is a small table that I made in wood shop when I was twelve years old. I still use it every day. The table is hardly a masterpiece of design, but it is made of solid pieces of real wood and it is very heavy for its size. Before I made this table, I created other pieces of furniture that have long since been discarded. It took a semester to gain basic carpentry skills, but the end result was competence sufficient to build a table that has lasted far longer than the junk that currently passes for furniture at most mass market retailers.

Wood shop was my favorite subject in middle school because I was able to produce something tangible that I could immediately use. I was encouraged to pursue academic subjects that would supposedly result in a better career compared to “manual labor” but I still wonder whether I might have been happier pursuing a trade. Most trades, whether carpentry, plumbing, construction, or a garden service, provide something that is immediately recognized for its value. Many trades pay very well, particularly for those who transition from being a laborer to owning a business that employs others.

In many professions, it is immediately apparent whether an individual has competence. If you visit a dentist for a root canal, you will find out very quickly whether he knows what he is doing. It is easy to determine whether a chef or a waiter in a fine restaurant has competence. The time that elapses between providing a good or service and evaluation of competence is very brief. In such fields, incompetent people are quickly identified and shunned, especially in today’s world of online reviews.

In my opinion, the majority of ambitious people are best off in careers where competence is obvious.

There is a great deal of satisfaction that comes from being very good at your craft and seeing quick results. There is even more satisfaction that comes from having your skills widely recognized by others. This satisfaction involves more than monetary benefits. The prestige associated with being among the best in your field creates tremendous self-esteem and this is critical for most people who are driven to rising high in life. For most people, there are severe limits to the concept of measuring their worth by an “inner scorecard.” Ambitious people usually hope to be held in high esteem by friends, family, colleagues, and employers.

When it comes to investing, competence is not obvious until an individual has a very long track record.

This statement is controversial because academic finance is dressed up with mathematical precision and it seems like it should be possible to measure an investor against the market and draw conclusions relatively quickly. In one of my college investment classes, the term paper involved picking three stocks at the start of the quarter. For each stock, students were expected to present an investment thesis. There is nothing wrong with such an exercise if the goal is to judge how well a student is thinking about the businesses represented by the ticker symbols. But part of the paper involved measuring stock price performance over the quarter and calculating measures, such as a stock’s beta, over a trivially short period of time.

The intention of the professor was to make textbook concepts come to life in a “real world” situation, but the message that he sent was that we can measure investment performance over a single quarter. This is obviously not the case. It takes multiple years to separate the signal from the noise when it comes to investment decisions. More specifically, it takes many years to determine if an investor’s results are due to skill rather than luck. Over a single quarter or a single year, it is quite possible for a very skilled investor to produce poor returns or for a totally incompetent investor to produce eye-popping returns.

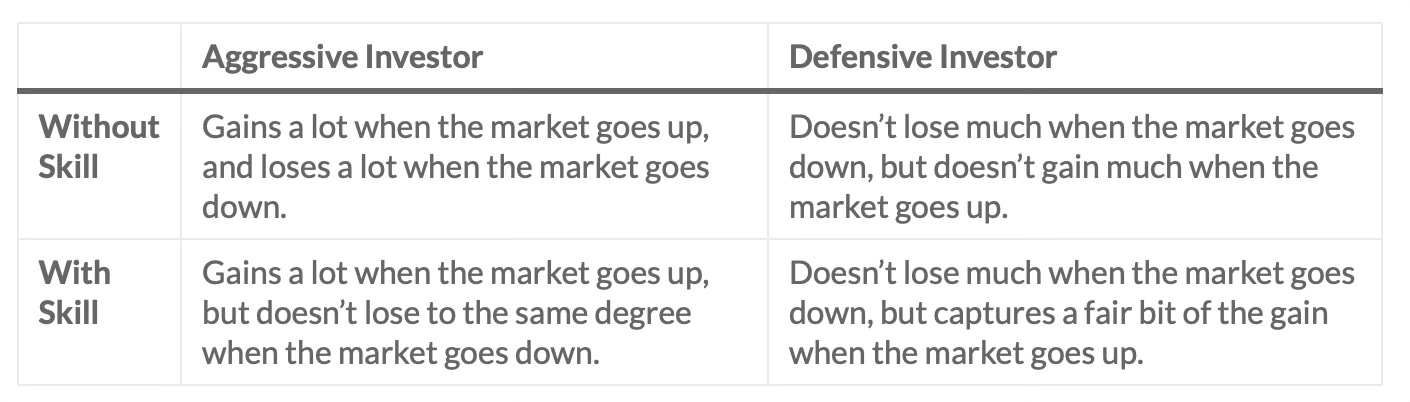

In The Most Important Thing, Howard Marks wrote about how we can determine whether an investor is adding value. The two-by-two matrix that he presented told the story in broad strokes:

In the book, Howard Marks goes into much more detail regarding how to measure the value that an investor brings to the table, but the bottom line is that some sort of asymmetry must exist. This is because achieving the “market” return takes no skill at all since anyone can invest in an index fund to achieve market returns. Furthermore, any investor can add leverage to the mix as well. For this reason, an aggressive investor who beats the market only by assuming far greater risks adds no real value since an index fund investor deploying leverage could obtain similar results.

These are broad brush statements, and Howard Marks goes into more details in his book. The point I am trying to make in this article is that even obtaining the data points to perform these measurements requires many years and, ideally, many market cycles. It is impossible to determine whether an investor has real skill until we see the investor navigate at least two or three market cycles. Of course, this usually requires a decade or more since many market cycles last for several years.

Investing is not the only field where skill is difficult to determine in the short run. Many social sciences, such as economics, are similar. How can we determine whether one of the hundreds of PhD economists employed at the Federal Reserve has any skill when it comes to forecasting the economy? It would take many economic cycles to be sure that such a person has any skill whatsoever.

Cognitive dissonance occurs when one’s self-image is not matched by reality. For investors, it is agonizing to admit that they might not have any skill until they have a ten or fifteen year track record. Imagine how devastating it would be to put all that effort into a career only to realize that you have no real skill a decade later. What would you do at that point? Dentists, carpenters, and musicians don’t have this problem!

A “solution” to this problem is to substitute another externally measurable factor for investing skill.

Many investors, particularly those who wish to attract large amounts of capital, focus on looking and acting the part. The ability to speak well and to present an aura of confidence and competence is very important in the investing profession. These skills are actually important even for those who have genuine investing skills, but they are even more important for those who lack investing skills. The ability to appear on financial television and seem to know what you’re talking about is critical, and it makes it less important whether your track record actually matches the persona you are presenting.

Aside from attracting capital or finding new employment opportunities, a successful public persona also provides immediate feedback. You are complimented on a confident performance on television immediately by your colleagues. Your family will be proud of your public image and neighbors and acquaintances will know that you are important and rising in your career. Couple this with driving the right type of car and living in the right kind of home and the investor will be getting immediate feedback on his or her “value.”

Of course, none of these factors have anything to do with whether the investor is providing meaningful value as an investor. One can have great verbal and written communication skills and a polished public persona while having no investing skills whatsoever. The same is obviously true in many academic fields and, most glaringly, among the political elites, many of whom have never added any value at any point in their careers.

After a quarter century of investing, all in a personal capacity, I am still not certain whether I had much skill even though I have (very modestly) outperformed the S&P 500.

After some early success during the dot com bubble and its aftermath, which I later realized was dumb luck, I made many errors in during the financial crisis of 2008. At the time, I wrote all the right things about coping with meltdowns, but my level of risk aversion prevented me from fully benefiting from the rebound in 2009. I soldiered on through the 2010s, even when my investments seemed to not be working out well early in the decade, but my overall record looked good going into the pandemic. I wrote about coping with meltdowns again, but this time I acted more rationally. I am most proud of posting a low single digit positive return in 2022 when the S&P 500 was down sharply.

I like to think that I fall into the bottom right quadrant of the matrix presented by Howard Marks:

“Doesn’t lose much when the market goes down, but captures a fair bit of the gain when the market goes up.”

This seems to most accurately reflect my overall track record, but the outperformance is probably not enough to really know for sure whether luck did not play the deciding role.

When it comes to luck, I must credit recognizing the value of what I call The Berkshire Hathaway MBA. I understood the value of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s wisdom early in life and I’ve benefited from this tremendously, both as an investor in Berkshire Hathaway and as an investor in general. Without this education, there is no doubt that I would have suffered catastrophic losses during the dot com bubble and I would have lost the seed capital that formed the foundation for a large part of my current net worth.

If I had not stumbled across Roger Lowenstein’s Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist when it was published in the summer of 1995, there is no doubt that my net worth would be a small fraction of what it has grown to today. That was certainly luck.

I did not invest in Berkshire in 1995 because I did not have enough money to buy a single share and I did not invest in 1996 when the Class B stock was introduced because Warren Buffett warned investors that the stock was no bargain. I started buying the stock in February 2000 when it was being hammered in the market at the tail end of the dot com bubble. I used the proceeds from selling Intel stock to make my initial purchase. Was this luck or skill? I know that I would not have done this without becoming familiar with Warren Buffett’s investing approach, but I cannot say whether it was luck or skill.

Should young people go into investing?

I would not discourage someone who truly dreams of succeeding in this field and has a mindset that is resistant to short-term opinions of others and receptive to the principles so well explained by Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger. It would be wrong to throw cold water on someone’s dream. But I would advise the young person to be prepared to objectively look at their performance over time and to develop multiple skills. It would be far easier to shift to another, more suitable, line of work later in life with a broad multidisciplinary skill set. Otherwise, it is too easy to fall into denial and end up looking back at a long career realizing that you added little value.

Even if you end up with a high net worth, which is quite possible for highly polished professional investors with little investing skill, realizing that you provided little value in exchange for the wealth is not a recipe for solid self-esteem or happiness later in life.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Individuals associated with The Rational Walk own shares of Berkshire Hathaway.