Made in America: Sam Walton's Story

The founder of Wal-Mart spent his final months writing an autobiography. The book contains timeless advice for retailers, investors, and anyone interested in business.

“I’m really sick these days, and I guess when you get older, and illness catches up with you, you naturally turn just a little bit philosophical — especially late at night when you can’t sleep and your mind is turning everything over and over trying to take stock of where you’ve been and what you’ve done. The truth is that if I hadn’t gotten sick, I doubt I would have written this book, or taken the time to try to sort my life out. … Temperamentally, I’m much too biased toward action to undertake such a sedentary project. But since I have, I’m going to go all the way and try to share with you how I feel about some things that seem important to me.”

— Sam Walton

Sam Walton retired as CEO of Wal-Mart in 1988 at the age of seventy. This was his second attempt at retirement, having failed to give up the reins in the mid-1970s. Walton was a retailer at heart and could never bring himself to completely walk away from the company he founded, so he remained active and continued to fly his plane from one Wal-Mart location to another, checking on how business was doing at the individual store level and speaking with employees.

In the late 1980s, at the urging of his family, Walton started writing his autobiography. When Walton was diagnosed with a form of bone cancer in early 1990, he naturally wanted to spend his remaining time doing what he loved to do so he cancelled the book project and focused on Wal-Mart. By the end of 1991, with the end in sight and his mobility impaired, Walton returned to the book project and worked on it nearly every day for the next several months nearly up to his death. The result is that the world has access to a first-hand account of Walton’s life in Made in America: My Story.

Early Days

Sam Walton was forty-four years old when the first Wal-Mart opened in the town of Rogers, Arkansas. Although well into middle age when his first eponymous store came into being, Walton was hardly a neophyte when it came to retailing. He had spent his entire career in retail starting as a management trainee in 1940 at a J.C. Penney in Des Moines at a salary of $75 per month. He was a natural salesman while at J.C. Penney but one high ranking company executive doubted that he could succeed due to his poor penmanship on sales slips. This executive told Walton, “I’d fire you if you weren’t such a good salesman. Maybe you’re just not cut out for retail.”

A minor heart condition prevented Walton from serving overseas during the Second World War, but he did serve stateside in the Army from 1942 to 1945, his only break in a fifty year retail career. There never seemed to be any doubt that Walton would return to retailing after the war. He was clearly motivated by the uncapped income potential, having witnessed his J.C. Penney manager in Des Moines earning what was then an astronomical annual bonus of $65,000. However, Walton was not cut out to work for a large corporation. He would opt to set out on his own as an entrepreneur.

Walton grew up during the Great Depression and worked his way through high school and college. By the time he got out of the Army in 1945, he had already been married to Helen Robson for two years and the young couple had about $5,000. This was not quite enough to get started as an entrepreneur, but Walton knew that he could borrow money from his father-in-law who was a prominent lawyer, banker, and rancher.

Like many entrepreneurs with limited capital, Walton got his start in franchising. He purchased a Ben Franklin variety store franchise for $25,000 using $5,000 of his own money and $20,000 borrowed from his father-in-law.1 The store was located in the small town of Newport, Arkansas in the Mississippi River delta. After two weeks of training in Arkadelphia, Walton opened his store on September 1, 1945. That date, seventeen long years before the first Wal-Mart opened, marked Sam Walton’s start as a retailing entrepreneur. He was twenty-seven years old.

Starting out in Newport

Retailing in the 1940s and 1950s bore no resemblance to what we have regarded as a normal shopping experience over the past several decades. Especially in small towns, the choice of retailers could be extremely limited and there were no “one stop shops”. Typically, shoppers would come in from rural communities on Saturdays and go to several retailers for essential purchases. Customers would ask a clerk behind the counter for items — self-service was not yet a concept.

The variety store concept, sometimes known as five and dimes, crossed product categories to sell a wider assortment of merchandise in a single location. The Ben Franklin chain was one of the major variety store players in post-war America and Sam Walton set out to improve the concept. At first, he lacked basic business skills and made several mistakes, especially related to real estate.

In just five years, Walton transformed the Newport store from a struggling operation with just $72,000 in annual revenue to a successful small business with $250,000 in revenue and $30,000 to $40,000 per year in profits. His store was the number one Ben Franklin location in terms of sales and profits in his six state region. He got to that point by trying all sorts of innovative tactics such as installing an ice cream machine, bypassing the Ben Franklin distribution system when necessary, and offering prices below nearby competitors.

Unfortunately, Walton’s initial naiveté came back to haunt him. Walton’s landlord in Newport operated a competing store and declined to renew the lease at any price!

The landlord ended up buying the Newport store and Walton had to start over again in Bentonville, Arkansas. At the time, Bentonville was less than half the size of Newport, but it was closer to Helen Walton’s family and provided access to quail hunting seasons in four states, one of Sam Walton’s lifelong interests.

“We were innovating, experimenting, and expanding. Somehow over the years, folks have gotten the impression that Wal-Mart was something I dreamed up out of the blue as a middle-aged man, and that it was just this great idea that turned into an overnight success. It’s true that I was forty-four when we opened our first Wal-Mart in 1962, but the store was totally an outgrowth of everything we’d been doing since Newport — another case of me being unable to leave well enough alone, another experiment. And like most other overnight successes, it was about twenty years in the making.”

— Sam Walton

Walton’s Five and Dime

Although still a Ben Franklin franchisee, Sam Walton chose to call his new store in Bentonville “Walton’s Five and Dime”. For a small town, Walton’s four thousand square foot location was very large and his implementation of a self-service concept with a central checkout register at the front of the store was a unique innovation. He soon opened a second store in nearby Fayetteville. Building on the experience gained in Newport, Walton turned the early Walton’s Five and Dimes into major successes.

Expansion continued throughout the 1950s as Walton reinvested profits from one store into a new one and repeated the process several times. During this period, Walton purchased his first plane and began to fly over small towns in Arkansas and Kansas looking for potential opportunities and store locations from the air. This is a habit that he would maintain for the rest of his life. By the end of the 1950s, Sam Walton ran the largest independent variety store chain in the United States.

“That whole period — which scarcely gets any attention from most people studying us — was really very, very successful. In fifteen years’ time, we had become the largest independent variety store operator in the United States. But the business itself seemed a little limited. The volume was so little per store that it really didn’t amount to that much. I mean, after fifteen years — in 1960 — we were only doing $1.4 million in fifteen stores … I began looking around hard for whatever new idea would break us over into something with a little better payoff for all our efforts.”

— Sam Walton

Discount Stores

Walton soon found the new idea he was looking for. Retailers were emerging that did volumes of business unheard of in the variety store industry. Early discounters were doing up to $2 million in sales per store, more in a single location than in Sam Walton’s entire network of fifteen variety stores.

Early discounters operated on the philosophy of “Buy it low, stack it high, sell it cheap.” Sam Walton soon learned about Sol Price’s success with FedMart, a discount retailer based in California. In 1962, S.S. Kresge Company opened the first K-Mart and Dayton-Hudson opened the first Target. These were large and well established retailers with far greater financial resources and operational experience and they grew very rapidly. Within five years, K-Mart had 250 stores and sales of $800 million.

Many who knew Sam Walton thought he had lost his mind when he threw hit hat into the discounting business. However, he spotted an opportunity that the larger players were ignoring. Conventional wisdom was that discount retailing at scale could only work in places with a larger population than the small towns Walton operated in. This allowed Wal-Mart to operate under the radar for many years. During the early years, no one really took any notice of Sam Walton and his small chain of Wal-Marts operating in places some would now call “flyover country”.

“Many of our best opportunities were created out of necessity. The things that we were forced to learn and do, because we started out under financed and undercapitalized in these remote, small communities, contributed mightily to the way we’ve grown as a company. Had we been well capitalized, or had we been the offshoot of a large corporation the way I wanted to be, we might not ever have tried the Harrisons or the Rogers or the Springdales and all those other little towns we went into in the early days. It turned out that the first big lesson we learned was that there was much, much more business out there in small-town America than anybody, including me, ever dreamed of.”

— Sam Walton

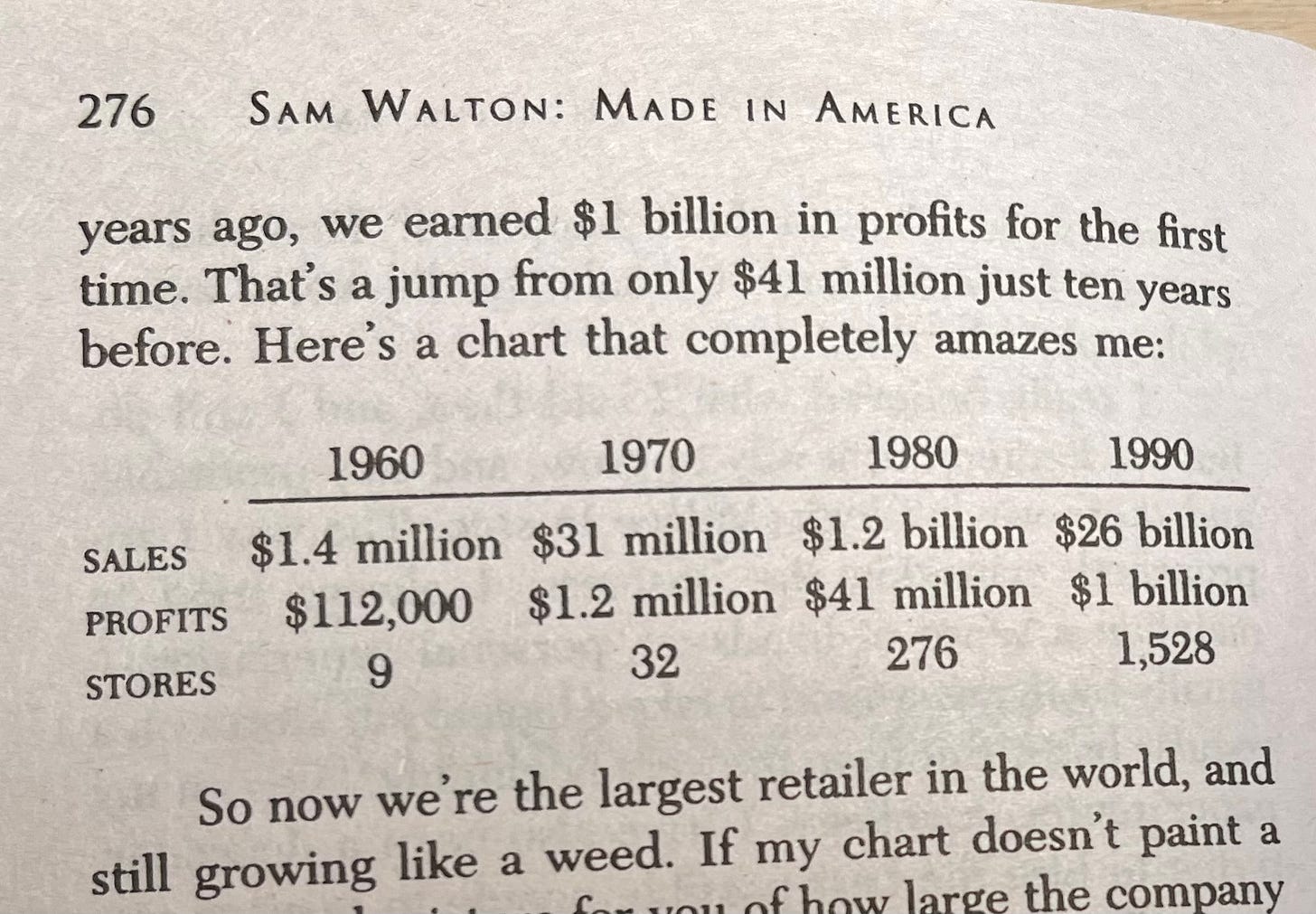

Much later in the book, Walton presents a table showing the dramatic growth of his business over the next three decades. Having lived through the entire experience, Walton admitted to still being completely amazed by the figures:

If there’s one thing that should jump out at readers, it is that Wal-Mart’s growth story exhibits all of the characteristics of an exponential function. While the growth during the 1960s was certainly impressive, it pales in comparison with what took place over the subsequent two decades.

One key reason for the company’s accelerating growth was that Walton decided to take Wal-Mart public in 1970. Up to that point, the company was funded through a combination of reinvested profits and debt backed by the Walton family. The fact that Walton was able to grow his empire into a $31 million chain of 32 stores by 1970 with very limited outside capital is remarkable.

Management and Culture

Wal-Mart’s evolution as a public company has received far more attention than Sam Walton’s early days but I find those formative years much more interesting which is why I have spent more time describing them. The book contains a great deal of information regarding Walton’s management style during the 1970s and 1980s, including an aborted attempt at retirement in the mid 1970s. The man just had no capacity to slow down and while he was capable of delegating key functions, he was wired to be the ultimate boss calling the shots.

It is apparent that without a strong executive team, Wal-Mart might not have grown so rapidly and could have declined during the 1980s. In particular, Walton had a penchant for frugality that could sometimes backfire. The company was always behind in terms of opening distribution centers and Walton resisted investing in technology at times. Ultimately, however, he deserves credit for writing the checks when necessary and delegating authority for key logistical operations in areas where other executives proved more capable than he was.

No one personified Wal-Mart more than the company’s founder. In addition to his insistence on providing the lowest possible prices for customers, Walton wanted his stores to be welcoming and pleasant places. At one point, he issued a challenge to employees to never get within ten feet of a customer without smiling and asking if they needed any help. Although the idea of a Wal-Mart greeter was not Walton’s idea, he quickly embraced the concept since it served the dual function of welcoming honest customers to the store and acting as a deterrent against shoplifting.

As someone who never shopped at Wal-Mart until the late 2000s, it is difficult to imagine the type of culture that prevailed in the stores during Sam Walton’s leadership of the company. When I think of Wal-Mart today, I think of relatively low prices but I do not think of friendly employees or any kind of customer service. After shopping at Wal-Mart for many years, I recently switched to Costco and find it far superior in every way. Of course, Wal-Mart is also in the warehouse club industry with Sam’s Club, a concept that Sam Walton admits to “borrowing” from Sol Price:

“So one day in 1983 I went to see Sol in San Diego. I had met him earlier when my son Rob and I called on him. This time, though, Helen and I were out on the West Coast already for a meeting of the mass merchandisers, so we dropped down to have dinner with Sol and his wife Helen at Lubock’s. And I admit it. I didn’t tell him at the time that I was going to copy his program, but that’s what I did.”

— Sam Walton

In 1983, Walton opened the first Sam’s Club and it was “almost what you’d call a second childhood” for him. He had an opportunity to begin anew with another company, one that he went out of his way to separate from Wal-Mart in terms of culture. Later in the 1980s, Walton went to a Price Club in San Diego and was using a small tape recorder to store his impressions of the warehouse and make notes on pricing. A large security guard noticed Walton and confiscated his tape recorder! Already well into his sixties and an extremely wealthy man, Sam Walton never lost his enthusiasm for merchandising and remained a fierce competitor to the end.

Controversies

Wal-Mart has always attracted controversy, at least ever since the company grew to the point where it was noticed by competitors and the media. Critics allege that the rise of discounting caused small town America to decline and that the company has not shared enough of its success with employees. Sam Walton closes the book by vigorously defending himself against these type of complaints.

Walton argues that he has always served the customer and the customer is ultimately the one who makes the decision about where to shop. In his view, Wal-Mart did not cause small town businesses to fail. Customers were the ones who fired small businesses that were charging higher prices and providing poor service. Walton believes that his company has saved customers in small communities billions of dollars and improved their lives as a result. It is hard to argue with the numbers. Wal-Mart offered demonstrably lower prices to customers by operating efficiently and accepting lower gross margins. Customers voted with their pocketbooks.

In terms of employee relations, Walton admits that he tended to be too restrictive with pay when he first started out but he loosened his policies over time, first with managers he partnered with in early stores and later with rank-and-file employees, many of whom reaped significant rewards as Wal-Mart grew and its stock price rose. One wonders how many of these early Wal-Mart employees remain with the company today and how their successors have fared in comparison. The company certainly continues to attract criticism for low wages today.

It seems to come down to culture yet again. When Sam Walton was active in the business, flying from store to store in his small plane and talking to rank-and-file employees, hosting events at his home and leading employees in corny “cheers”, and generally rallying the troops, the culture was alive and well. People will respond positively to a charismatic leader that they can believe in and Sam Walton was such a leader. The same is not necessarily true in a mega-cap company that doesn’t seem to have retained the culture in the three decades since Walton’s death.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that Sam Walton was a legendary retailer who took the risks, made the personal sacrifices, and had the right personality to build one of America’s great businesses. He did not necessarily come up with all of the ingredients for his success, but he was relentless and focused every single day for many decades. He never took his eyes off the ball, he focused on competitors, and never stopped trying to improve.

Toward the end of his autobiography, Walton reflects on his life and priorities and asks himself whether all of the personal sacrifices were worth the results. His verdict was that he would make the same trade-offs again:

“I can honestly say that if I had the choices to make all over again, I would make just about the same ones. Preachers are put here to minister to our souls; doctors to heal our diseases; teachers to open up our minds; and so on. Everybody has their role to play. The thing is, I am absolutely convinced that the only way we can improve one another’s quality of life, which is something very real to those of us who grew up in the Depression, is through what we call free enterprise — practiced correctly and morally. And I really believe there haven’t been many companies that have done the things we’ve done at Wal-Mart. We’ve improved the standard of living of our customers, whom we’ve saved billions of dollars, and of our associates, who have been able to share profits. Many of both groups also have invested in our stock and profited all through the years.”

— Sam Walton

Wal-Mart had recently surpassed $50 billion of net sales and Walton hoped that the company would double that figure by 2000. His successors accomplished the goal in 1997, three years ahead of schedule. Wal-Mart had net sales of $605.9 billion in fiscal 2023, more than ten times the level when Sam Walton left the scene three decades ago.

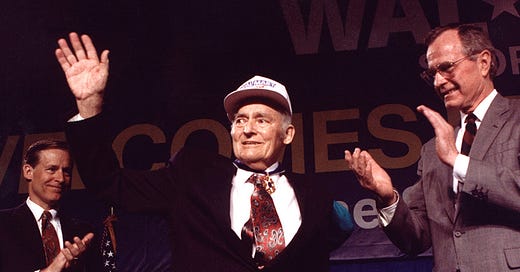

On March 17, 1992, Sam Walton was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. One cannot help but be impressed with his brief speech upon accepting the award. Sam Walton died on April 5, 1992, less than three weeks later.

If you find this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider sharing this issue with your friends and colleagues or on social media.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this newsletter constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

While the initial investment in the first Ben Franklin franchise seems tiny to modern readers, we should keep in mind that $25,000 in September 1945 dollars is equivalent to $417,000 in March 2023 dollars, at least according to the official CPI data maintained by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Sam Walton funded this purchase with the equivalent of roughly $83,000 of personal capital in today’s dollars plus $334,000 from his father-in-law. When I was 27, such figures would certainly have seemed like a large amount of money.

Thank you for sharing this story