Hesiod’s Works and Days

One of the oldest surviving books provides advice that is just as relevant to our lives today as it was over 2,700 years ago.

It can be depressing to consider how little we know about ancient civilizations.

Before the invention of the printing press in the middle of the fifteenth century, the written word was preserved in hand-written manuscripts produced by scribes and monks. This labor-intensive process acted as a filter. Only the most important works were preserved over the centuries. There is no doubt that much that was worthy failed to make the cut. For example, we know that less than ten percent of the plays written by Aeschylus have survived. Most of the creative and historical works produced in the ancient world are lost.

Hesiod was a poet who lived in Greece in the eight century BC. We do not know the exact span of his life and it is possible that he was active even before Homer. He lived toward the end of what is known as the Greek Dark Age, a period from 1200 BC to 800 BC when civilization had regressed and the written script of the Mycenaean civilization fell out of use. Hesiod and Homer composed poetry in the oral tradition, but the introduction of the Phoenician alphabet in Greece allowed their works to be preserved. While Homer is far more celebrated today, Hesiod provides a very interesting window into Ancient Greek civilization on the cusp of revitalization that would last several centuries and culminate in a new golden age.

There is little doubt that Hesiod produced many more works than the two poems which have been preserved. The son of a merchant seaman from Asia Minor who immigrated to Boeotia, Hesiod made his living as a farmer and herder on the eastern slopes of Mount Helicon. In Theogony, Hesiod claims divine inspiration as the source of his insights into the origin of the Greek gods. We are presented with a detailed, and admittedly sometimes tedious, accounting of the origins of the earth and heaven, the rise of the Titans, and their eventual overthrow leading to the supremacy of the Olympian Gods led by Zeus.

Hesiod’s Theogony is interesting but it was probably only comprehensible because I previously read Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. Although not a primary source, Hamilton does an excellent job making the Greek gods understandable and her book is the best choice for most readers interested in the subject. I found Hesiod’s Works and Days to be far more interesting than Theogony. Both works are included in the Oxford World’s Classics edition translated by M.L. West.

In Works and Days, Hesiod shares his wisdom about living a good life in Ancient Greece. While much of his advice has to do with the agricultural seasons, he shares some timeless wisdom as well that resonates throughout the ages. Ostensibly produced as a set of instructions for Perses, his wayward brother, Hesiod was really addressing a much broader audience. His advice is not that far from what we read in other ancient wisdom literature. At times, I was reminded of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes in the Old Testament. Technology advances but the human condition has remained relatively constant, so the pitfalls and snares Hesiod spoke of twenty-seven centuries ago can help us live a better life today.

The agricultural guidance is fascinating because it is linked to astronomical, botanical, and climatological signs that triggered certain activities appropriate for the seasons. There’s a time to plow, a time to sow, a time to harvest, and times to allow fields to lie fallow. All of this and more is discussed, with plenty of warnings of what can go wrong when activities occur out of season. However, modern readers are more likely to find Hesiod’s advice on life more interesting than his views on when to plow a field, and I have selected several such excerpts from Works and Days to allow Hesiod to speak for himself.

Good and Evil

As for those who give straight judgments to visitors and to their own people and do not deviate from what is just, their community flourishes, and the people blooms in it. Peace is about the land, fostering the young, and wide-seeing Zeus never marks out grievous war as their portion. Neither does Famine attend straight-judging men, nor Blight, and they feast on the crops they tend. For them Earth bears plentiful food, and on the mountains the oak carries acorns at its surface and bees at its centre. The fleecy sheep are laden down with wool; the womenfolk bear children that resemble their parents; they enjoy a continual sufficiency of good things. Nor do they ply on ships, but the grain-giving ploughland bears them fruit.

But for those who occupy themselves with violence and wickedness and brutal deeds, Kronos’ son, wide-seeing Zeus, marks out retribution. Often a whole community together suffers in consequence of a bad man who does wrong and contrives evil. From heaven, Kronos’ son brings disaster upon them, famine and with it plague, and the people waste away. The womenfolk do not give birth, and households decline, by Olympian Zeus’ design. At other times again he either destroys those men’s broad army or city wall, or punishes their ships at sea.

Works and Days, p. 41-42

For if a man is willing to say what he knows to be just, to him wide-seeing Zeus gives prosperity; but whoever deliberately lies in his sworn testimony, therein, by injuring Right, he is blighted past healing; his family remains more obscure thereafter, while the true-sworn man’s line gains in worth.

Works and Days, p. 45

Hard Work

Hunger goes always with a workshy man. Gods and men disapprove of that man who lives without working, like in temper to the blunt-tailed drones who wear away the toil of the bees, eating it in idleness. You should embrace work-tasks in their due order, so that your granaries may be full of substance in its season. It is from work that men are rich in flocks and wealthy, and a working man is much dearer to the immortals. Work is no reproach, but not working is a reproach; and if you work, it will readily come about that a workshy man will envy you as you become wealthy. Wealth brings worth and prestige. But whatever your fortune, work is preferable, that is, if you turn your blight-witted heart from others’ possessions toward work and show concern for livelihood as I tell you.

Works and Days, p. 46

If your spirit in your breast yearns for riches, do as follows, and work, work upon work.

Works and Days, p. 48

Work, foolish Perses, do the work that the gods have marked out for men, lest one day with children and wife, sick at heart, you look for livelihood around the neighbours and they pay no heed. Twice, three times you may be successful, but if you harass them further, you will achieve nothing, all your speeches will be in vain, and however wide your words range its will be no use. No, I suggest you reflect on the clearing of your debts and the avoidance of famine.

Works and Days, p. 49

I am confident that you will be happy as you draw on the stores under your roof; you will reach the bright spring in prosperity, and not look towards others, rather will another man be in need of you.

Works and Days, p. 51

Kindness and Charity

Invite to dinner him who is friendly, and leave your enemy be; and invite above all him who lives near you. For if something untoward happens at your place, neighbours come ungirt, but relations have to gird themselves. A bad neighbor is as big a bane as a good one is a boon: he has got good value who has got a good neighbor. Nor would a cow be lost, but for a good neighbor. Get good measure from your neighbor, and give good measure back, with the measure itself and better if you can, so that when in need another time you may find something to rely on. Seek no evil gains: evil gains are no better than losses.

Works and Days, p. 47

For if a man gives voluntarily, even a big gift, he is glad at the giving and rejoices in his heart; but if a man takes of his own accord, trusting in shamelessness, even something little, that puts a frost on the heart.

Works and Days, p. 47

The tongue’s best treasure among men is when it is sparing, and its greatest charm is when it goes in measure. If you speak ill, you may well hear greater yourself. And be not of bad grace at the feast thronged with guests: when all share, the pleasure is greatest and the expense least.

Works and Days, p. 58

Do as I say; and try to avoid being the object of men’s evil rumour. Rumour is a dangerous thing, light and easy to pick up, but hard to support and difficult to get rid of. No rumour ever dies that many folk rumour. She too is somehow a goddess.

Works and Days, p. 59

Procrastination

Do not put things off till tomorrow and the next day. A man of ineffectual labour, a postponer, does not fill his granary: it is application that promotes your cultivation, whereas a postponer of labour is constantly wrestling with Blights.

Works and Days, p. 49

Many are the ills that a workshy man, waiting on empty hope, in want of livelihood, complains of to his heart. Hope is no good provider for a needy man sitting in the parlour without substance to depend on. Point out to your laborers while it is still midsummer: ‘It will not always be summer. Built your huts.’

Works and Days, p. 52

Avoid shady seats and sleeping till sunrise at harvest time, when the sun parches the skin. At that time get on with it and gather home the harvest, rising before dawn so that your livelihood may be assured.

Works and Days, p. 54

Compounding, Risk, and Redundancy

For if you lay down even a little on a little, and do this often, even that may well grow big. He who adds to what is there, wards off burning hunger. What is stored up at home is not a source of worry; better for things to be in the house, for what is outside is at risk. It is good to take from what is available, but sorrow to the heart to be wanting what is not available. I suggest you reflect on this.

Works and Days, p. 48

Take the trouble to provide yourself with two ploughs at home, a self-treed one and a joined one, for it is much better so: if you should break one, you can set the other to the oxen.

Works and Days, p. 50

Do not put all your substance in ships’ holds, but leave the greater part and ship the lesser; for it is a fearful thing to meet with disaster among the waves of the sea, and a fearful thing if you put too great a burden up on your cart and smash the axle and the cargo is spoiled. Observe due measure; opportuneness is best in everything.

Works and Days, p. 57

Hopefully these excerpts from Works and Days provide a sense of Hesiod’s style and sound life advice.

There is much more that he has to say, and I think that many readers would profit from reading this short work. At just twenty-five pages, it is more of an essay than a book and can be read in about an hour. Many of the themes he deals with are timeless and appear in other ancient wisdom literature. The Mediterranean had a high degree of economic and cultural integration during Hesiod’s lifetime and it is very likely that he either influenced or was influenced by books of the Old Testament such as Proverbs.

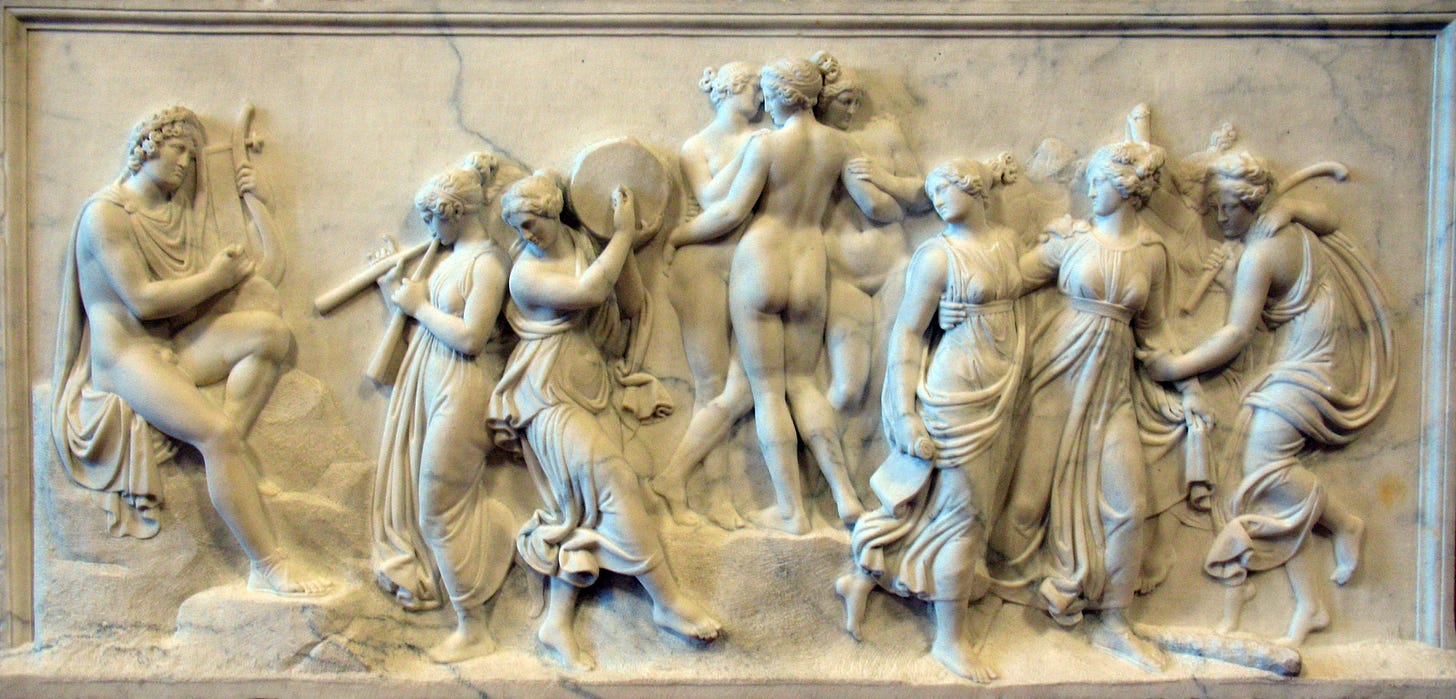

The scene below shows the dance of the Muses on Helicon, the site of Hesiod’s inspiration for Theogony.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Great recap!