Buffett Continues to Avoid Long-Term Bonds

Berkshire's longstanding aversion to fixed-maturity investments has not changed in response to higher interest rates.

Berkshire Hathaway reported third quarter results over the weekend. I wrote a brief article yesterday containing an overview of the quarter. In the past, I have typically published a long article discussing selected aspects of Berkshire’s results in greater detail. This quarter, I’m writing a series of shorter articles instead.

Analyzing a conglomerate as large as Berkshire can be a formidable task. Sometimes a formidable task is best approached in smaller pieces. This article is an analysis of Berkshire’s portfolio of marketable securities with a focus on the allocation to longer-term bonds. Apparently, higher interest rates have not been sufficient for Warren Buffett to reallocate funds from short-term treasury bills to longer term bonds.

Equity Securities

Warren Buffett’s tremendous success over seven decades has long attracted the attention of investors who hope to either copy his moves or to gain insight into his views regarding opportunities in financial markets.

Most investors focus on Mr. Buffett’s moves in the stock market. Much information is available regarding Berkshire’s holdings of stocks traded on exchanges in the United States since regulations require the company to file 13-F reports every quarter. In certain cases where Berkshire owns a large percentage of a company, such as Occidental Petroleum, investors learn of Mr. Buffett’s activities within a few days. The temptation to coat tail can be overwhelming for many traders and investors.

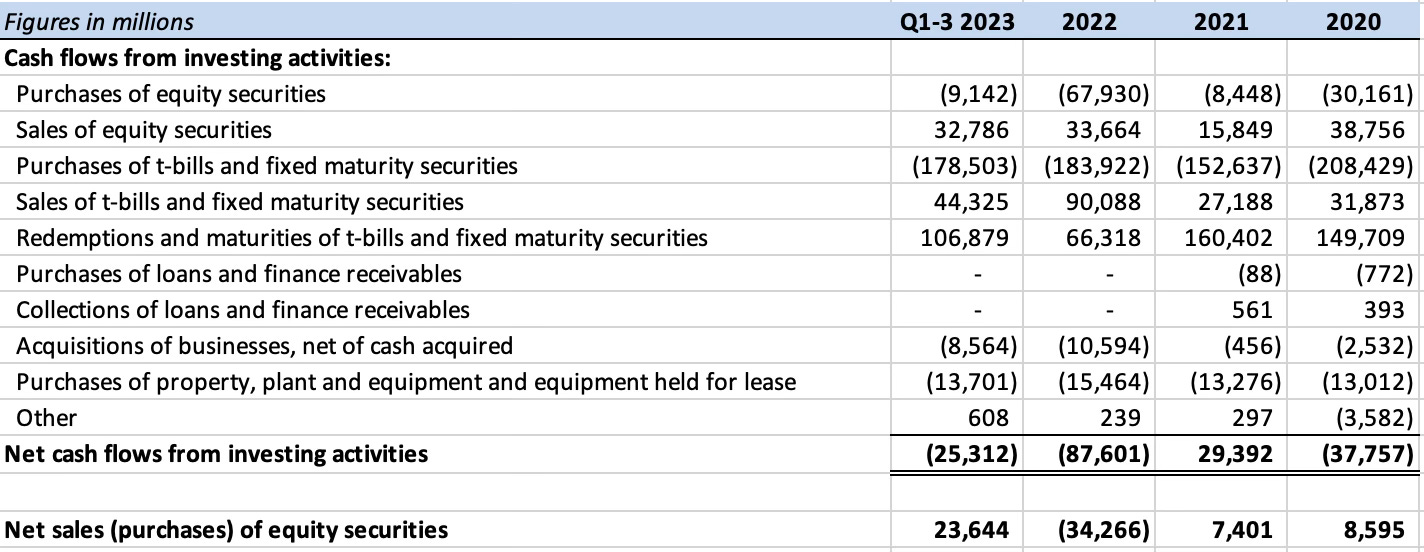

Investors are also interested in whether Berkshire is a net buyer or seller of stocks in a given quarter. This information can be derived from Berkshire’s cash flow statements. Berkshire provides annual cash flow statements as well as year-to-date cash flow statements in quarterly reports. This information is summarized below:

If we add up “Purchases of equity securities” and “Sales of equity securities”, we arrive at the net figure, which is shown as the last row in the exhibit. A positive number indicates net sales of equity securities while a negative number indicates net purchases. We can see that Berkshire was a net seller of equity securities in 2020 and 2021, a net buyer in 2022, and a net seller for the first nine months of 2023.

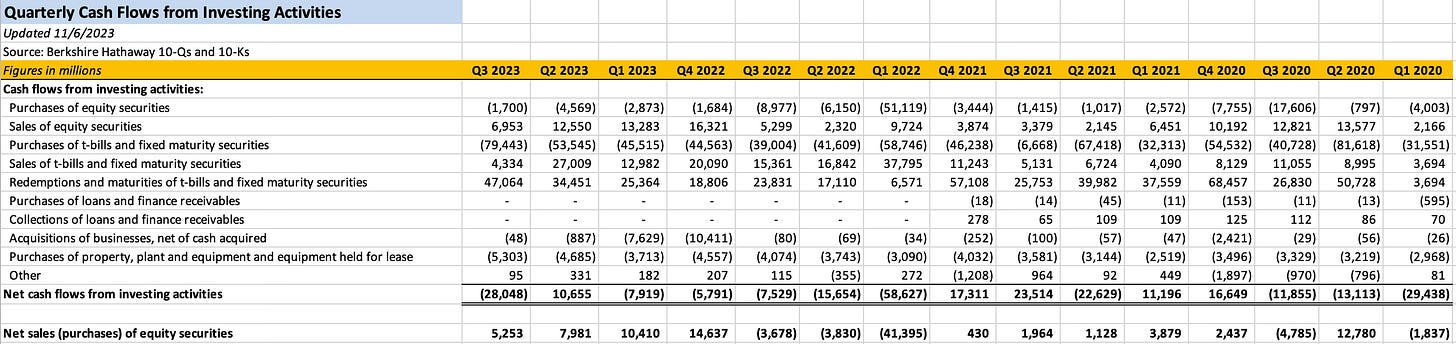

We can drill down further and derive quarterly cash flow information, which I have done in the following exhibit. (Click on the image for a larger view)

From the quarterly figures, we can see that Berkshire has been a net seller of equity securities for the past four quarters. The net sales total $38.3 billion over this period.

Berkshire’s 13-F report for the third quarter has not been filed yet, but we can examine the specific moves made by the company in U.S. exchange-traded equities up to the second quarter. The dataroma website provides a useful display of changes in Berkshire’s portfolio for each quarter going back several years.

While it is interesting to follow Berkshire’s equity portfolio, I take a dim view of coat tailing. But there’s nothing wrong with identifying ideas to independently research. For example, Berkshire’s investment in Floor & Decor, most likely a pick of either Todd Combs or Ted Weschler, led me to look into the company in 2021. Berkshire’s heavy investment in oil and gas stocks in the first quarter of 2022 was also interesting, although I am very happy to fully delegate my oil and gas investing to Warren Buffett!

Although Berkshire’s 13-F for the third quarter has not been filed, we can infer that shares of Chevron were sold during the quarter, as I explained in my Q3 overview article. We also know that Berkshire sold shares of HP since the company is required to disclose transactions within three days as a 10% owner. In October, Berkshire resumed purchases of Occidental Petroleum shares, as I described in a recent article.

Can we infer that Warren Buffett is generally bearish on stocks due to Berkshire’s net sales of equities over the past four quarters?

I doubt that Mr. Buffett and his deputies are making a market timing statement. Instead, they are not finding opportunities large enough for Berkshire to invest in while sales are being triggered by a stock either reaching full value or because the investment thesis has changed, (which is the likely reason for the HP sale). I would hesitate to interpret sales of equities to be a general commentary on the stock market.

Cash, Treasury Bills, and Bonds

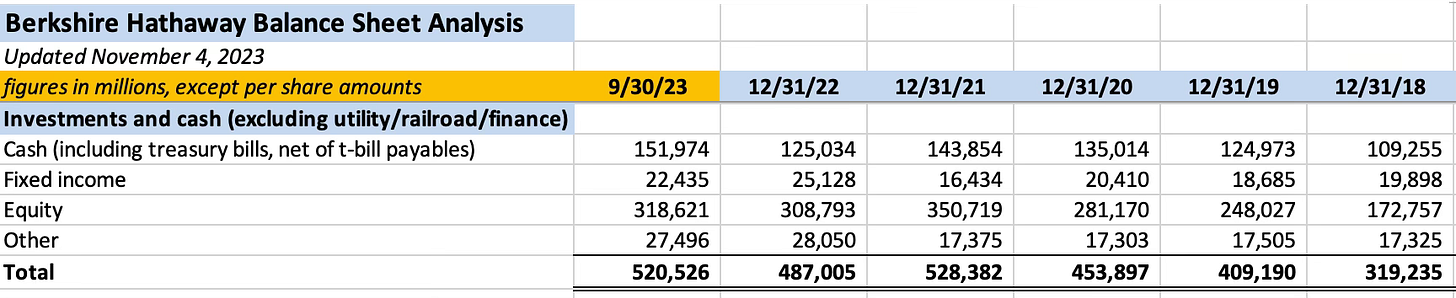

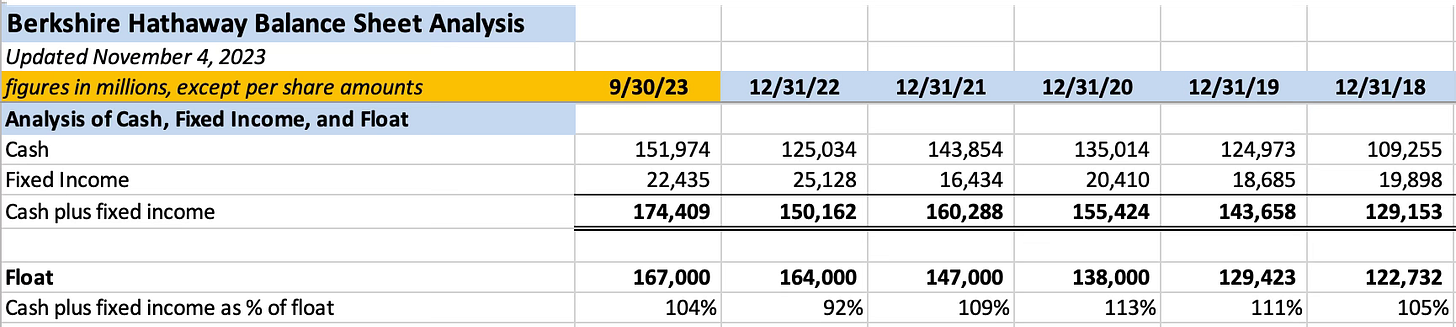

The following exhibit shows the composition of Berkshire’s investment portfolio since the end of 2018. I have aggregated cash and treasury bills in this exhibit.

Berkshire’s approach to investment allocation is highly unorthodox in the insurance industry. Most insurance companies hold a very large allocation of fixed-maturity investments. Bonds form the cornerstone of an insurance company’s portfolio because managers attempt to match the duration of the bonds with cash flows needed to satisfy policyholder liabilities. In Berkshire’s case, bond investments have long been far lower than one would expect given the size of the company’s insurance operations.

Warren Buffett shunned longer term bonds due to the microscopic interest rate environment that prevailed from the financial crisis until very recently. On multiple occasions, Mr. Buffett explained that stocks were far superior to bonds from an earnings yield basis. It made little sense for Berkshire to tie up funds in longer term bonds earning next to no interest.

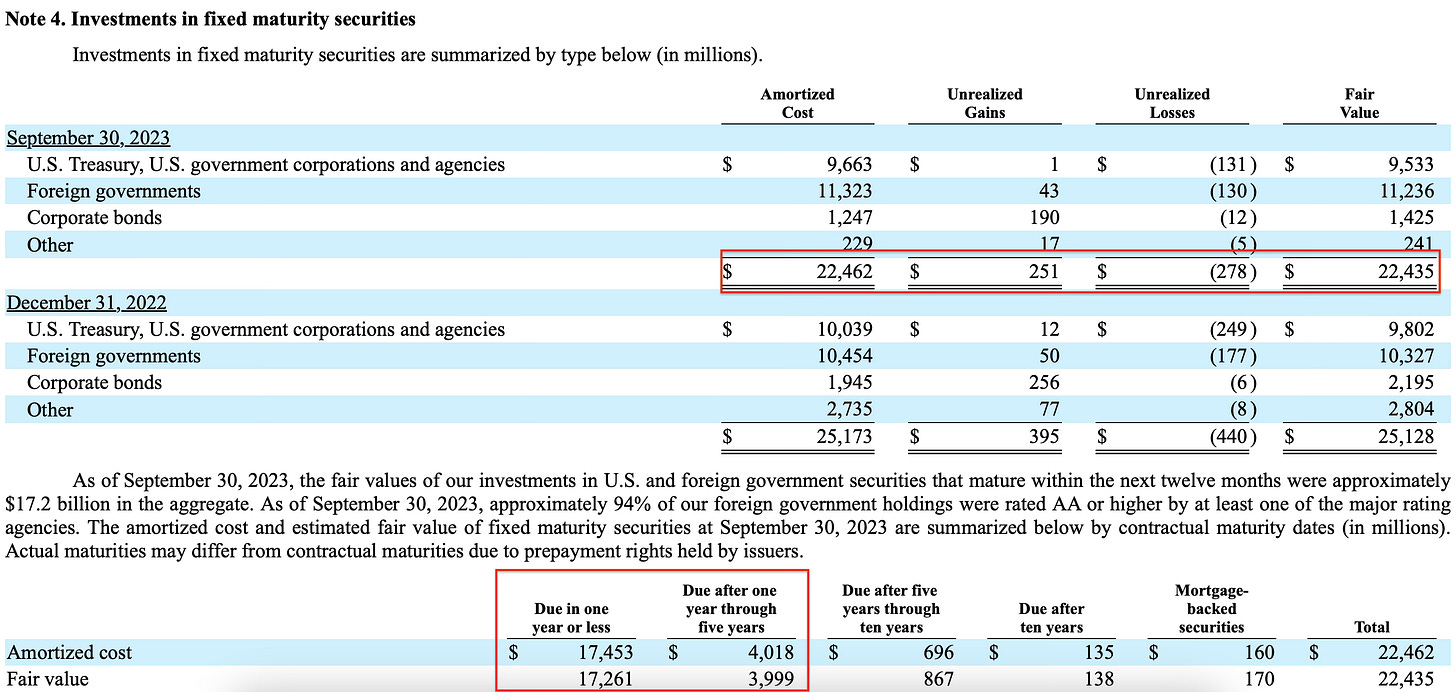

As I explained in an article in March, investing in longer term bonds can be very painful in a rising rate environment. Berkshire has emerged almost totally unscathed due to the very short duration of the portfolio. The exhibit below from the 10-Q shows how conservative Warren Buffett has been when it comes to bond investing:

Not only is Berkshire’s $22.4 billion allocation to bonds tiny compared to its $520.5 billion investment portfolio, 77% of the bond portfolio is due in one year or less, with nearly the rest due within five years. Berkshire is barely exposed to long-term bonds.

Berkshire does have long-term liabilities, but Warren Buffett doesn’t believe in duration-matching. He does, however, appear to believe in a conservative asset allocation when one considers the bigger picture. The exhibit below shows Berkshire’s total float along with the company’s allocation to cash and bonds:

Berkshire has long maintained a combined total of cash and bonds that is quite similar to float. In other words, a significant portion of Berkshire’s cash appears to be there as a substitute for bonds. Warren Buffett has not wanted to take any duration risk, which has paid off in a rising rate environment.

Many observers think that Berkshire could deploy a majority of the $152 billion of cash on the balance sheet for acquisitions. While it is certainly possible that Berkshire could make a very large acquisition, it does not seem to me that anywhere near $152 billion of cash is available for an acquisition. Much of this cash is likely there as conservative ballast against expected policyholder liabilities. Berkshire has always been run in an extremely conservative manner. I doubt that will change.

Why Avoid Longer Term Bonds?

Howard Marks rarely makes big macro calls, so it has been quite interesting to read his recent memos which refer to the rising interest rate environment as a “sea change.” Warren Buffett is known to admire Howard Marks and is a regular reader of his memos. Mr. Marks is a specialist in credit, particularly high yield credit, and sees opportunities for investors to achieve equity-like returns in credit markets:

“The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index has returned just over 10% per year for almost a century, and everyone’s very happy (10% a year for 100 years turns $1 into almost $14,000). Nowadays, the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Constrained Index offers a yield of over 8.5%, the CS Leveraged Loan Index offers roughly 10.0%, and private loans offer considerably more. In other words, expected pre-tax yields from non-investment grade debt investments now approach or exceed the historical returns from equity. And, importantly, these are contractual returns.”

I should be clear that Howard Marks is referring to high-yield bonds in this statement. In other words, these are issues from companies that are not investment grade and have significant default risk. Long-term treasury bonds have recently offered yields in the 5% range, far from the high yield index that Mr. Marks refers to.

Berkshire is very conservative, but owning a large portfolio of equities, particularly in companies with less of a firm “moat”, is also a risky proposition. Berkshire tends to concentrate its equity holdings in companies that Mr. Buffett believes have a strong moat. But that is not a universal characteristic of all stocks in the portfolio. Moving up the capital structure while still earning equity-like returns is attractive to Howard Marks but, at least up to this point, has not tempted Warren Buffett.

Conclusion

Warren Buffett has not always had an aversion to longer term bonds. As I wrote in September, Mr. Buffett recommended longer term bonds to partners when he wound down the Buffett Partnership in 1970. That recommendation did not turn out so well as inflation raged in the 1970s and early 1980s.

It seems reasonable to believe that 5% on longer-term treasuries does not tempt Mr. Buffett when compared to treasury bills paying 5.5%. With an inverted yield curve, investing in long-term treasuries involves a sacrifice to income while taking on duration risk. However, there is no guarantee that short term rates will not decline in the future, which seems to be the consensus market expectation. The logic for investing in longer term bonds is to lock in a higher yield for a longer period of time.

My inference is that Warren Buffett does not consider current longer term treasuries attractive, probably because his expectations for inflation are above the market consensus. If inflation averages 3-4% over the next decade rather than 2%, the yield curve is likely to shift up, with treasury bills paying 5-6% and longer term treasuries paying 6-7% or more. If this is Mr. Buffett’s view, it makes sense to stick with t-bills.

I doubt that Berkshire will do much in the type of high-yield bonds that Howard Marks specializes in, even if they offer equity-like returns. However, we can be sure that Warren Buffett is well aware of the types of opportunities that have attracted Howard Marks recently and perhaps interesting opportunities will arise in the future.

At the risk of ending this article on a negative note, I am less enthusiastic than most investors about Berkshire’s jump in interest income in recent quarters. We should be focusing on real returns. When inflation rages, as it has for the past two years, the higher interest income Berkshire receives on its large cash holdings merely provides a partial offset to the loss of purchasing power. The fact is that Berkshire’s large allocation to cash over the past few years has been subject to a massive “inflation tax”. We can be sure that Warren Buffett is painfully aware of this reality.

This article is exclusively for paid subscribers. If you found this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider referring a friend to The Rational Walk.

Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Long Berkshire Hathaway.