Berkshire Hathaway's Retained Earnings Test

This article is the third in a series of responses to questions from readers.

November 18, 2023

Dear Readers,

I have removed the paywall from this article which was originally published on June 28, 2023. One of the benefits of purchasing a paid subscription includes substantial coverage of Berkshire Hathaway from the perspective of a longtime shareholder. Every quarter, I review Berkshire’s results and write articles that I believe go into greater depth than what is typically published in the mainstream financial media.

Thanks for reading!

This is the third and final article in response to questions from readers.

The first two articles, published on June 21 and 23, covered performance disclosures for Berkshire’s investment managers, the reinsurance outlook, inflation, insider ownership, and worst case scenarios:

To gain full access to all questions and responses, as well as to other exclusive content, please consider a paid subscription. The Rational Walk is a reader supported publication and I appreciate those who choose to support my work.

Thanks for reading!

If you find this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider sharing it with your friends and colleagues or on social media.

The Owner’s Manual

Berkshire Hathaway’s shareholders have an unusually long term perspective and are typically well aligned with management’s unique style of operations. The company’s corporate ethos first developed when Warren Buffett took control in 1965 and was reinforced when Berkshire shares were distributed to limited partners as Mr. Buffett wound down his investment partnership at the end of 1969.

Berkshire’s shares historically turn over less than other companies but there have been occasions when the shareholder base has changed materially in a short period of time. Berkshire’s merger with Blue Chip Stamps in 1983 caused the shareholder base to grow and Mr. Buffett considered it important to communicate Berkshire’s operating principles to new owners.1 He set down thirteen owner-related business principles intended to help new shareholders understand Berkshire’s approach.

When Berkshire issued Class B stock in 1996, this resulted in an influx of new shareholders, many of whom were previously “priced out” due to the high price of Class A stock. This presented Mr. Buffett with the challenge of welcoming a large number of new owners who may have purchased shares without fully understanding his approach.2 In June 1996, the thirteen owner-related principles communicated to Blue Chip shareholders in 1983 were republished as An Owner’s Manual in a booklet sent to all Berkshire shareholders. The manual was reprinted in Berkshire’s annual reports until 2017 and the latest version is still available on the company’s website.

The Owner’s Manual remains relevant to shareholders even though it is no longer included in annual reports. Our focus today is on Principle #9 which has to do with the question of whether or not management should retain earnings.

Deploying Free Cash Flow

Before getting into Berkshire’s retained earnings test, it is important to understand that we are referring to “owner earnings”, a concept that is closely related to free cash flow and almost never identical to net income defined by generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Warren Buffett explained owner earnings in his 1986 letter to shareholders as part of his discussion of the Scott Fetzer acquisition.

Owner earnings is calculated as reported earnings plus depreciation, depletion, and amortization minus the average annual capitalized expenditures for plant and equipment required to maintain the company’s competitive position and unit volume. In addition to these items, we should also recognize that Berkshire’s reported earnings are distorted, especially over short periods of time, due to the inclusion of unrealized gains and losses on the company’s large portfolio of equity securities.

Five years ago, I wrote Thoughts on Share Repurchases and Capital Allocation which describes the options for management to deploy free cash flow. I came up with the following possible options which are more fully described in the article:

Expand current business operations.

Pursue business opportunities in adjacent or unrelated areas.

Pursue acquisitions.

Accumulate cash.

Return capital to shareholders.

Berkshire Hathaway is a conglomerate made up of hundreds of business units, each of which have unique economic characteristics. The conglomerate structure allows free cash flow to move between business units in a tax efficient manner. This is a major advantage. For example, despite management’s many attempts, See’s Candies has been unable to reinvest its prodigious free cash flow to expand the business. Similarly, BNSF has been a provider of cash for Mr. Buffett to allocate to other opportunities. In contrast, Berkshire Hathaway Energy has been able to redeploy all of its free cash flow.

Despite Warren Buffett’s desire to bag “elephants”, opportunities to acquire businesses of a size large enough to “move the needle” have been few and far between in recent years. As a result, cash has accumulated on Berkshire’s balance sheet. In 2018, Berkshire changed its repurchase policy and began to buy back shares and the pace picked up significantly starting in 2020. Between August 2018 and March 2023, Berkshire used $70.5 billion to repurchase shares.

The rest of this article is a discussion of Berkshire’s retained earnings test, as originally formulated in 1983 and as amended in 2010. As we go through this discussion, we should be cognizant of the fact that Berkshire has been returning a significant amount of cash to shareholders over the past five years, an implicit recognition that management has found it difficult to deploy capital in other ways. The fact that Berkshire has accomplished this return of capital via repurchases rather than dividends is an expression of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s view that shares have been trading below intrinsic value, “conservatively determined”.3

Berkshire’s Retained Earnings Test

Berkshire’s original retained earnings test reads as follows:

“We feel noble intentions should be checked periodically against results. We test the wisdom of retaining earnings by assessing whether retention, over time, delivers shareholders at least $1 of market value for each $1 retained. To date, this test has been met. We will continue to apply it on a five-year rolling basis. As our net worth grows, it is more difficult to use retained earnings wisely.

We continue to pass the test, but the challenges of doing so have grown more difficult. If we reach the point that we can't create extra value by retaining earnings, we will pay them out and let our shareholders deploy the funds.”

[Emphasis Added]

The test was revised significantly after the 2009 annual meeting when a question regarding the original test made Warren Buffett realize that the wording did not reflect his intentions.

The revised earnings test reads as follows:

“I should have written the ‘five-year rolling basis’ sentence differently, an error I didn’t realize until I received a question about this subject at the 2009 annual meeting.

When the stock market has declined sharply over a five-year stretch, our market-price premium to book value has sometimes shrunk. And when that happens, we fail the test as I improperly formulated it. In fact, we fell far short as early as 1971-75, well before I wrote this principle in 1983.

The five-year test should be: (1) during the period did our book-value gain exceed the performance of the S&P; and (2) did our stock consistently sell at a premium to book, meaning that every $1 of retained earnings was always worth more than $1? If these tests are met, retaining earnings has made sense.”

[Emphasis added]

The revised retained earnings test requires two conditions to be true:

Berkshire’s increase in book value must exceed the performance of the S&P 500 on a five year rolling basis. Although not explicitly stated, I would interpret this to mean book value on a per share basis.

Berkshire’s stock must consistently sell at a premium to book value.

In early 2014, I pointed out that Berkshire did not pass the retained earnings test in 2013. Although Berkshire’s stock traded above book value, the gain in book value per share from 2009 to 2013 failed to surpass the performance of the S&P 500. I speculated that a return of capital was more likely than in the past, but I also noted that book value as a proxy for intrinsic value growth was becoming less relevant over time.

I suspect that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were already on the verge of saying goodbye to book value as a performance measurement by early 2014. However, book value was not formally dropped from its longstanding featured location on page two of Berkshire’s annual reports until 2018.

I wrote Warren Buffett Moves the Goalposts!, to analyze Mr. Buffett’s decision to drop book value, which he described in his 2018 letter to shareholders. I concluded that the change made logical sense given the growing importance of operating businesses to Berkshire and the gap between book value and market value of key operating companies. I used the example of BNSF which continued to be carried on Berkshire’s books at historical cost even though we knew that market value was far higher due to the market capitalization of Union Pacific. The same was clearly true for many of Berkshire’s businesses and this effect has grown wider over the past five years.

Berkshire’s Performance

I decided to analyze Berkshire’s performance starting at the turn of the century because I became a shareholder in February 2000 so this period reflects my own experience, at least when it comes to early shares, all of which I still hold today. I looked at performance in terms of growth of shareholders’ equity, book value per share, and market value per share. Although we have data for the first quarter of 2023, I cut off this analysis at the end of 2022 to look only at full year periods.

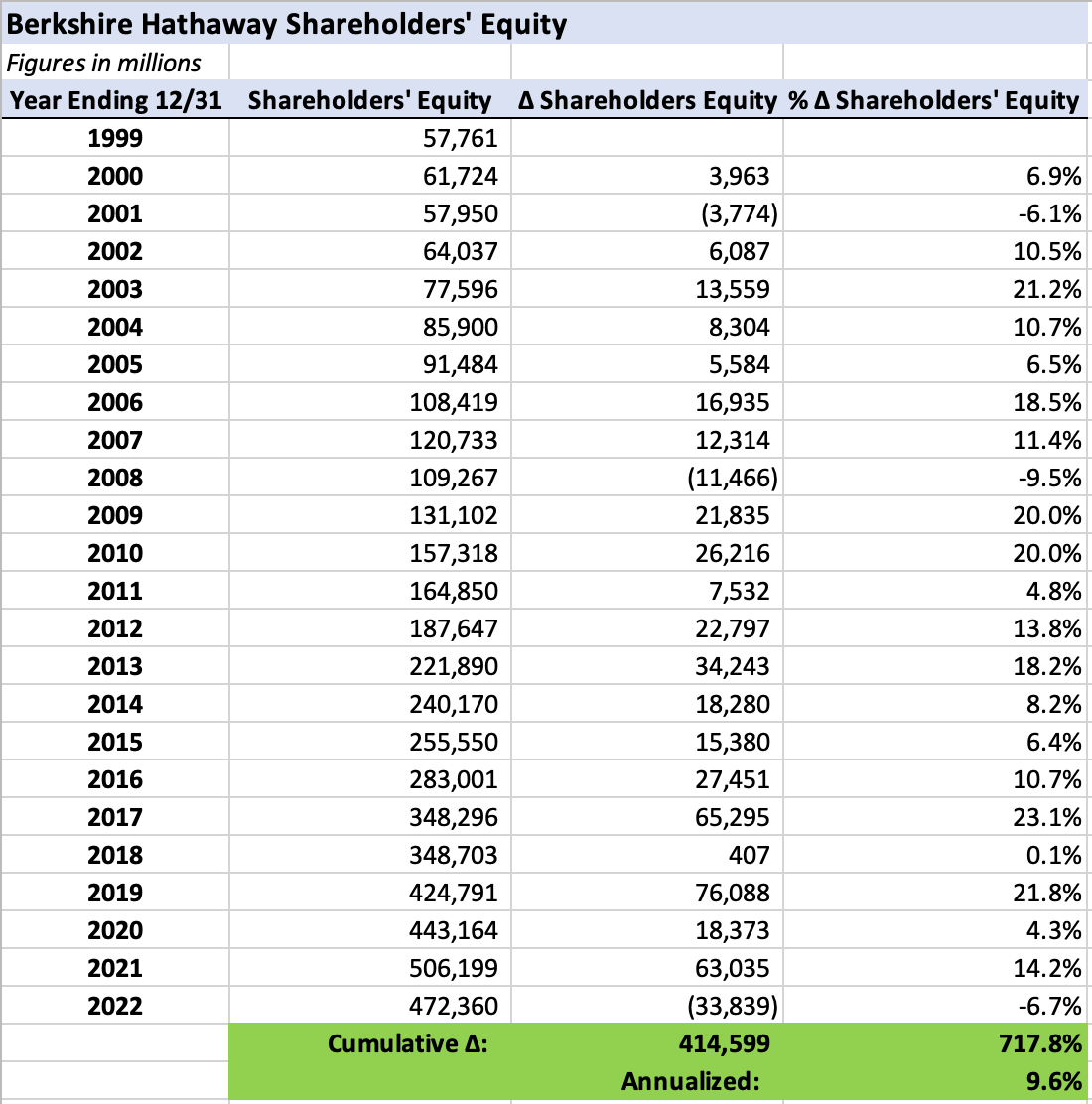

The following table shows Berkshire’s shareholder’s equity:

For the twenty-three year period, Berkshire compounded shareholders’ equity at 9.6% annually with only three down years. There was only one major issuance of shares during this period which took place in 2010 to fund part of the BNSF acquisition.

It is not particularly useful to look at performance of shareholders’ equity without considering the number of shares outstanding, so let’s look at performance in terms of book value per Class A share, as shown in the following exhibit:

For the twenty-three year period, Berkshire compounded book value per share at 9.8% annually with three down years. Why did book value per share compound faster than shareholder’s equity? There were fewer shares outstanding on December 31, 2022 compared to December 31, 1999 thanks to significant share repurchases over the past five years. The overall shrinkage in share count is even more notable in light of the share issuance in 2010 required to fund a portion of the BNSF acquisition.

Shareholders cannot pay their rent or buy food with book value per share, and even long term oriented shareholders must eventually care about market prices. How has Berkshire’s Class A stock performed over the same timeframe?

For the twenty-three year period, Berkshire’s stock compounded at 9.7% annually with four down years. Why did Berkshire’s stock price compound at slightly less than the rate of book value growth? This was due to a very slight compression in the price/book ratio which stood at 1.48x on December 31, 1999 and 1.45x on December 31, 2022. Although the compression is minimal, it is notable given the growing importance of operating businesses and the shift in the composition of Berkshire’s value in recent years. We should expect the price/book ratio to increase over time.

Applying the Retained Earnings Test

Let’s turn our attention to comparing Berkshire’s changes in book and market value per share with the total return of the S&P 500 which has long been the benchmark appearing in Berkshire’s annual reports as well as in the retained earnings test.

The following exhibit shows changes in book value and market value per share on an annual basis for 2000 to 2022. Starting in 2004, I present a five year compound return figure for book value per share, market value per share, and the S&P 500 total return. For 2004, the calculation is the compound return for 2000 to 2004. For 2005, the calculation is the compound return for 2001 to 2005, and so on. Looking at performance on a five year rolling basis is called for in the retained earnings test in order to avoid focusing too much attention on the noise of year-to-year results.

The retained earnings test revised in 2010 calls for a comparison of changes in book value to the S&P 500 which is the data contained in the ∆ BVPS column. I also included a market value comparison in the ∆ MVPS column. The cells highlighted in green are “passing scores” while the cells highlighted in red are “failing scores”.

As noted previously, Berkshire began to fail the retained earnings test in 2013, and this remained the case for five years. After passing the test in 2018 and 2019, the test again failed over the past three years. The results are slightly different for market value, but the story that is told is similar: Berkshire has had difficulty consistently passing the retained earnings test, as revised in 2010, over the past decade.

But what if we look at the situation from a somewhat longer perspective? After all, five years is not a very long period of time and maybe we should consider a ten year rolling test. I should emphasize that this test is my own experiment. As far as I know, Warren Buffett has not proposed looking at ten year rolling periods.

The story doesn’t change very much when looking at the situation on a ten year rolling basis. The fact is that the S&P 500 has been a tough benchmark in the years since the financial crisis. On a positive note, at the end of 2022, Berkshire’s market value per share was slightly ahead of the S&P 500 over the trailing ten year period.

Taking an even longer view, Berkshire has outperformed the index from 2000 to 2022. A big part of that outperformance has to do with the S&P 500’s dismal performance during the first three years of the period as the market suffered from a severe hangover caused by frothy stock markets during the late 1990s.

A Formidable Competitor

The S&P 500 has proven to be a formidable competitor in recent years. It seems worth considering what the valuation of the S&P looks like today compared to where it has been over the past twenty-three years. One way to do this is to look at the cyclically adjusted P/E ratio, also known as the CAPE, P/E 10, or Shiller P/E. This data series is maintained by Robert Shiller and I created the following chart based on the spreadsheets provided on his website:

The Shiller PE uses real earnings per share over a ten year period to smooth out business cycle fluctuations. It can provide an indication of stock market valuations, although it is obviously backward looking. We can see that valuations were very high at the turn of the century and compressed during the 2000s, most dramatically during the financial crisis. Valuations expanded during the 2010s.

It might be tempting to suggest that comparing Berkshire against the S&P 500 in a period of rising valuations is unfair, but there is no reason to automatically suppose that Berkshire’s market value should necessarily trail the valuation of the S&P 500. Berkshire Hathaway is itself a component of the S&P 500 and is faced with the same macroeconomic headwinds and tailwinds as all other companies. A five year rolling period is a significant length of time and ten years is even longer. At some point, the “short run” becomes the “long run”.

Share Repurchases

If we take another look at the ten year rolling test, we can see that Berkshire began to fall behind in 2018. Is it a coincidence that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger ramped up repurchases starting in that year?

From August 2018 to December 2019, Berkshire used $6.4 billion to repurchase stock. The repurchase pace accelerated dramatically in 2020 to $24.7 billion, and accelerated even further in 2021 to $26.9 billion before slowing down to $8 billion in 2022. Berkshire repurchased $4.4 billion of stock in Q1 2023. In total, $70.5 billion has been used to repurchase stock in less than five years.

I recently analyzed repurchases in more detail so I’ll leave out further discussion here, but suffice it to say that Berkshire has been returning capital to shareholders. The fact that this major policy shift took place in 2018 rather than in 2014 when the retained earnings test first appeared to fail is not necessarily surprising. Allowing cash to accumulate for a short period of time was reasonable and provided Warren Buffett with optionality. I think that most shareholders were fine with that approach.

Large repurchases in recent years signal that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger believe that the shares are undervalued. Otherwise, they might have had to resort to dividends to return capital. Although I am sure that Mr. Buffett would be highly averse to dividends due to his own personal tax situation, he would probably have instituted a dividend if Berkshire had traded closer to 1.75x book value. That number is purely a guess on my part, of course. I have no idea exactly what Mr. Buffett thinks of Berkshire’s intrinsic value other than that it must be materially higher than the price he is paying to repurchase shares.

Conclusion

Warren Buffett has long recommended low-cost index funds as the ideal investment for individuals and has gone as far as to instruct the executor of his estate to invest the majority of his wife’s portfolio in the S&P 500. While I attribute part of Mr. Buffett’s stance on indexing to modesty and not wanting to appear self-promotional, there is no doubt that the S&P 500 has been a tough competitor for Berkshire in recent years.

Berkshire has still performed competitively, and one can argue that Berkshire is undervalued today while the S&P 500 is overvalued. I tend to agree with that line of thinking and am fine with Berkshire retaining cash, which it has done, in addition to repurchasing shares below intrinsic value. I would be far less happy with return of capital in the form of dividends since I hold the majority of my Berkshire stock in taxable accounts. I am sure that my distaste for dividends pales in comparison to how Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger feel about the topic give the size of their holdings.

A good question for next year’s annual meeting could be about how the retained earnings test should read today given that the reference to book value in the revised test no longer applies due to Berkshire dropping book value as a key metric. As far as I know, the retained earnings test has not been formally revised since 2010.

This also raises the question of whether there should be a specific mathematical test because such a test could tie the hands of Greg Abel and his successors in the future. Berkshire ultimately relies on what Charlie Munger has called a “seamless web of deserved trust”, not mathematical formulas, when it comes to stewardship. Assuming Berkshire’s culture remains intact, this will be as true in the future as it is today.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Long Berkshire Hathaway.

For some background on Blue Chip Stamps, I recommend reading my book review of Damn Right! — Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger. I also discussed Blue Chip in my book review of The Buffalo News: From Butler to Buffett.

When the Class B shares were offered, Berkshire issued a remarkable statement in a prospectus dated May 9, 1996 indicating that “Mr. Buffett and Mr. Munger believe that Berkshire’s Class A Common Stock is not undervalued at the market price stated above [$33,400]. Neither Mr. Buffett nor Mr. Munger would currently buy Berkshire shares at that price, nor would they recommend that their families or friends do so.”

See the 2022 annual report, page K-32: “Berkshire’s common stock repurchase program permits Berkshire to repurchase its Class A and Class B shares at any time that Warren Buffett, Berkshire’s Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, and Charles Munger, Vice Chairman of the Board, believe that the repurchase price is below Berkshire’s intrinsic value, conservatively determined. Repurchases may be in the open market or through privately negotiated transactions.”

Great job and thanks!

Excellent update on the Retained Earnings Test. Thanks for publishing.