In the spring of 1954, a scientist’s loyalty to his country was questioned in a hearing orchestrated by a powerful enemy. Five years later, the tables were turned and the scientist’s enemy was exposed and publicly humiliated in another hearing. The tragic story of J. Robert Oppenheimer encompasses far more than science and politics. It is a cautionary tale of human nature that holds timeless lessons.

Few Americans recall the 1950s which made Christopher Nolan’s task very difficult when he took on the challenge of portraying the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a controversial genius who played a key role in the development of atomic weapons during the Second World War. Nolan created a film that generated over $945 million in box-office ticket sales over a three month run in theaters. This is a tremendous achievement in an age of limited attention spans, especially given the subject matter.

When the film was released in July, I was skeptical that I would be able to follow the storyline given my limited knowledge of the Manhattan Project that resulted in the first atomic weapons. I was also unfamiliar with the intricacies of the postwar debate regarding further development of nuclear weapons. It seemed doubtful that a three hour movie could adequately convey what I knew was an extremely complex topic.

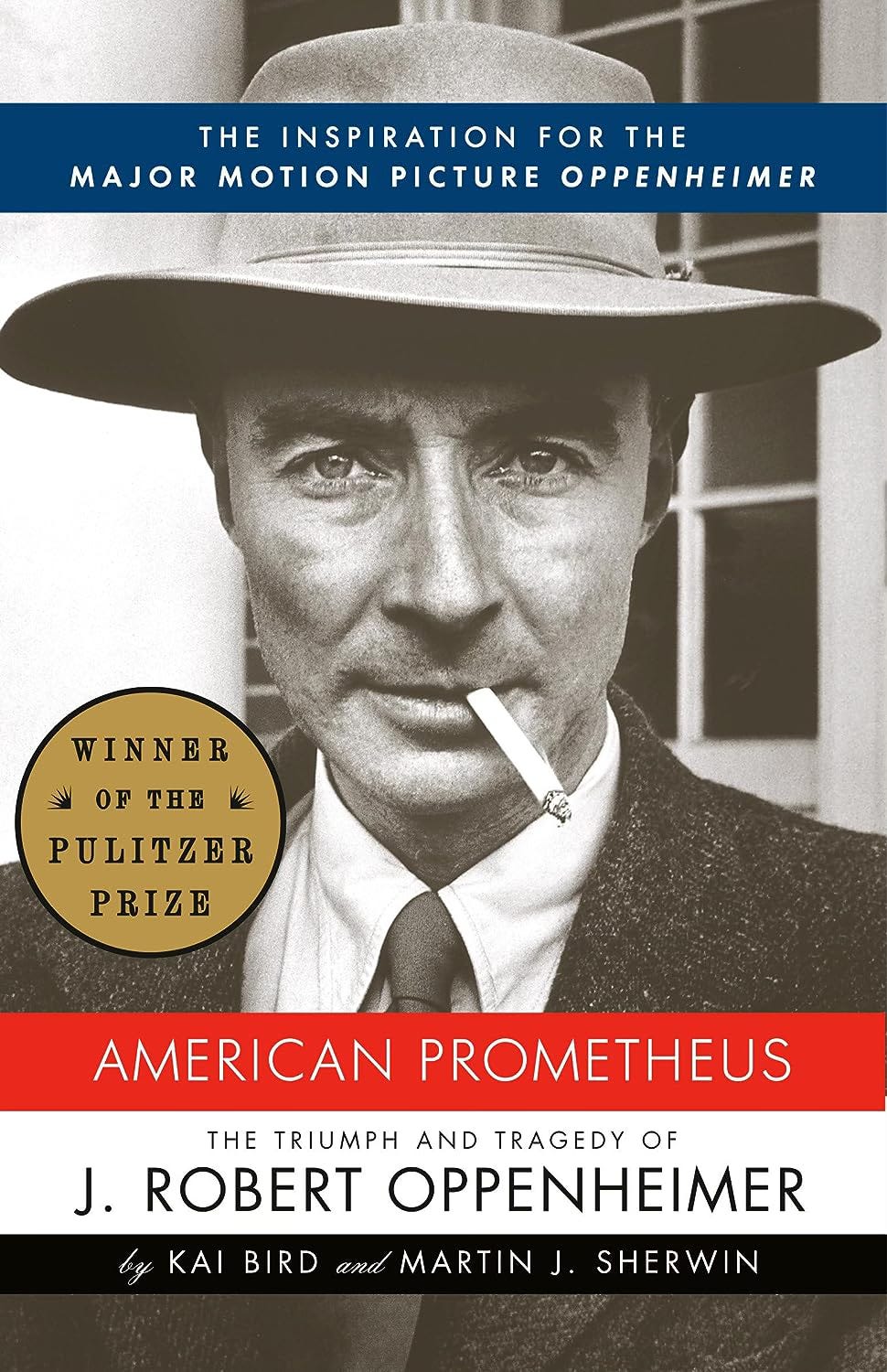

I decided to purchase American Prometheus, the definitive Oppenheimer biography that provided much of the source material for the film, and I finally got around to reading it this month. Fortunately, I finished the book just as the movie was about to disappear from theaters. Reading the book prior to going to the theater was definitely the right call. I wonder how those who have seen the film with limited background of the story are able to fully interpret the complex plot and dialog.

It would be impossible to cover a book spanning six hundred pages in a three hour film, at least without being quite dull. Nolan chose to omit Oppenheimer’s childhood and the vast majority of his early years in favor of a focus on his academic life in the 1930s and the Manhattan Project which began in mid-1942. With the Oppenheimer and Strauss hearings as points of departure, the film consists of a series of flashbacks to earlier years. This forms the basis for a very effective narrative arc.

Rather than attempt to summarize the book or the film, I will focus on a few key lessons that I think we can learn from the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Since it is likely that more readers of this article have seen the film than read the book, I will try to highlight nuances of the controversy based on events that were covered in more depth in print than on the screen.

Context Matters

“The items of so-called 'derogatory information' set forth in your letter cannot be fairly understood except in the context of my life and my work.”

At the age of seven, Robert Oppenheimer was enrolled in a private school run by a group called the Ethical Culture Society. The society was dedicated to social action and humanitarianism. According to American Prometheus, Ethical Culture was a reformist Judaic sect born in an environment in which Jewish businessmen in New York were grappling with anti-Semitism. Unlike members of the early Zionist movement, Ethical Culture members wanted Jews to lead “emancipated” lives within the diaspora. The society was not explicitly socialist but the founder had an affinity with certain elements of Marxism that dealt with the plight of the working class.1

Due to Oppenheimer’s early exposure to the beliefs of the Ethical Culture Society, which aligned closely to the beliefs of his parents, it was natural for him to drift toward the left side of the political spectrum. Although he is not portrayed as very political in his early years, an individual’s political views are often formed early.2 When the Great Depression began, Oppenheimer apparently felt some discomfort with the relative wealth he enjoyed due to his father’s business success and took an interest in advocating for those who fell into poverty.

In the film, we see the first signs of Oppenheimer’s political activity when he was at Berkeley as a young academic in the 1930s. At the time, the labor movement was very active with the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) taking a leading role in organized labor. With knowledge of Oppenheimer’s background from the book, it is clear that he fell into social groups at Berkeley primarily because of his family and early educational background in the Ethical Culture Society.

In the years leading up to the outbreak of World War II, the Spanish Civil War raged from 1936 to 1939. This conflict was between fascist forces loyal to General Francisco Franco and the Popular Front government of the Spanish Republic. The Popular Front was a left wing movement of anarchists, socialists, and communists who had allies within the CPUSA. Oppenheimer’s social circle included CPUSA party members determined to assist the Popular Front in the fight against fascism. Since Hitler was assisting Franco, the Spanish Civil War was thought of as an extension of the larger battle against fascism spreading through the rest of prewar Europe.

While Oppenheimer insisted that he never became a member of the CPUSA, he acknowledged funneling financial support to the forces fighting Franco via CPUSA. He also provided resources for the party to print pamphlets for other causes within the United States. Oppenheimer’s brother and sister-in-law were, at least for a period of time, CPUSA members. Jean Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s primary romantic interest during the late 1930s, and later his mistress, was also a dedicated CPUSA member.

Given Oppenheimer’s social circle, it comes as no surprise that he ended up marrying a woman with communist ties. Kitty Puening suffered directly due to the Spanish Civil War when her husband volunteered to fight and was quickly killed in action. Kitty acknowledged being a CPUSA member for a period of time but always insisted that Robert was never an official member.

Without understanding Oppenheimer’s early life and the influence of the Ethical Culture Society, it is difficult to understand his political activities. My impression, primarily from the book, is that most of the communists Oppenheimer associated with during the 1930s were idealists who had little comprehension of the tyranny that inevitably goes hand-in-hand with totalitarian communism. From an ideological perspective, these people seem not too different from current far left progressives.

There is no solid proof that Oppenheimer himself was ever a CPUSA party member, but this seems to be a distinction without a real difference given his close association with party members. Indeed, many of his closest friends thought that he was a party member. The bottom line, however, is that it meant one thing to associate with communists in the 1930s than it did to associate with communists in the 1950s.

Context matters and we should avoid retroactively applying later knowledge to judge the actions of people during another time. It seems that most of Oppenheimer’s social circle thought that they were helping the poor within the United States and assisting forces in Europe opposed to fascism. The Soviet Union was not yet a sworn enemy of the United States and indeed would become a wartime ally instrumental in taking on Hitler’s regime on the eastern front and suffering heavy losses.

Know Who Your Friends Are

Robert Oppenheimer is portrayed as the protagonist in the book and the film, but like all human beings, he was not without flaws. In an effort to protect one of his good friends, Oppenheimer made a grave mistake that directly led to his later troubles.

Oppenheimer was a brilliant physicist but was also a man of culture with a wide range of intellectual interests including literature. So it comes as no surprise that Oppenheimer found it interesting to talk to Haakon Chevalier, a specialist in French literature. Oppenheimer and Chevalier became close friends after they met at Berkeley in 1937. Chevalier’s membership in the CPUSA was nothing unusual.

At some point during the winter of 1942-43, while the Manhattan Project was underway, Oppenheimer and Chevalier had a brief discussion about a mutual acquaintance, George C. Eltenton, a physicist employed by the Shell Oil Company who offered to pass scientific information to a contact at the Soviet consulate.

Both Oppenheimer and Chevalier were concerned that the United States was not sharing information with allies during the war, including with the Soviet Union. While Chevalier did not know exactly what Oppenheimer was working on, he seemed willing to cross the line to espionage. Oppenheimer was not. He flatly rejected the approach while making martinis, and the men joined their wives for dinner.3

By this point, Oppenheimer was the head of the Los Alamos site and it is clear that he had a duty to report the approach and name Eltenton as a potential spy. However, it would be difficult to do so without implicating Chevalier in the matter. As a result, Oppenheimer waited several months before reporting the incident, and when he did, he invented what he later called a “cock and bull story” to protect his friend.4

In a fateful interview with Army officials in August 1943, Oppenheimer named Eltenton as a potential spy while also expressing his personal opinion that he was “friendly to the idea” of the United States providing the Russians with more information on the project. He stressed that he did not want it to move out “the back door”, meaning through Eltenton. However, apparently in an effort to protect Chevalier, he referred to approaches through multiple people and refused to specify any names unless ordered to do so. Several months later, Oppenheimer did provide Chevalier’s name when ordered to do so. This created an impression of evasion.

During this period of time, Oppenheimer was undergoing a period of rapid personal evolution as he assumed responsibility for a large organization at Los Alamos. Prior to the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer was not known for his management capabilities and few could see him in an official military role. In the six months after the approach from Chevalier, Oppenheimer’s biographers note that he had become a “changed man”, yet he continued to feel qualified to decide on his own who was a security risk and who was not. In his view, Eltenton was a risk but Chevalier was not.

Understanding Politics

It is natural that Robert Oppenheimer felt a sense of personal responsibility for how atomic weapons would be used. After all, his leadership at Los Alamos was critical. Under Oppenheimer’s direction, the United States successfully built atomic bombs that changed the course of history. However, the terrible nature of nuclear weapons weighed heavily on Oppenheimer for the rest of his life.

Oppenheimer celebrated with his team at Los Alamos when Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed in August 1945, but the reality is that he was conflicted about whether the use of nuclear weapons was necessary to end the war. He came to believe that Japan was already defeated and that Truman’s use of the bomb was more related to preventing the Soviet Union from incursions into Japan in the final days of the war.

In a meeting with Truman in late 1945, Oppenheimer told the President that he, Oppenheimer, felt that he had “blood on his hands” due to the use of the bomb on civilian populations. Predictably, this was highly offensive to President Truman and Oppenheimer had no further influence at the White House.

Oppenheimer was shocked that the President did not think that the Soviets would be able to develop their own nuclear weapons and he continued to advocate for a policy of openness and international control of the technology. He correctly foresaw the arms race that commenced immediately after the war and predicted that the Soviets would rapidly develop their own weapons. There is no evidence that Oppenheimer was, at any point, disloyal or tried to provide information to the Soviets “out the back door” but the impression that he disagreed with Truman’s policies hurt him politically.

Oppenheimer was a brilliant scientist but quite tone-deaf when it came to politics. He continued to speak his mind, understanding that he had a unique perspective to share and feeling a sense of responsibility to do so, yet he did not seem to comprehend that he was stepping on some powerful toes in the process.

Identify Your Enemies

The Atomic Energy Commission was created in 1946 to oversee development of atomic energy and technology during peacetime. Oppenheimer chaired the General Advisory Committee of the AEC which was comprised of nuclear scientists. The first Chairman of the AEC was David Lilienthal who saw eye-to-eye with Oppenheimer on the contentious issue of establishing international controls over atomic energy.

The most important debate of the early atomic age centered on the degree to which the United States should acknowledge the inevitability of other countries developing nuclear technology and take proactive steps to control proliferation. Oppenheimer was firmly on the side of arms control and opposed development of hydrogen thermonuclear weapons of far greater power than first generation atomic weapons.

Lewis Strauss saw the situation very differently. As a member of the AEC, Strauss was a strong proponent of aggressive development of the H-bomb. As a conservative Republican, Strauss and Oppenheimer were at polar ends of the ideological spectrum.

Despite these differences, in his capacity as a trustee for The Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, Strauss recruited Oppenheimer to serve as the Institute’s director in 1947. Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, Strauss and Oppenheimer found themselves in disputes both at the Institute and at the AEC. It is not clear whether it was intentional, but Oppenheimer publicly humiliated Strauss on a technical matter and Strauss held on to this grudge which eventually evolved into outright hatred.

Strauss rarely allowed his antipathy toward Oppenheimer to rise to the surface. However, looking past the polite veneer, Strauss worked relentlessly to marginalize Oppenheimer in the debate over the H-bomb and arms control. In July 1953, Strauss was appointed as Chairman of the AEC. At a time when fear of communist infiltration of the government was near its peak, Strauss had a perfect opening to use his power to permanently sideline Oppenheimer.

Due Process — Theory and Practice

The Oppenheimer security hearing was held in a shabby conference room behind closed doors. Spanning four weeks during the spring of 1954, the purpose was to consider whether Oppenheimer’s security clearance should be renewed. Although Strauss was not in attendance, he was the invisible hand directing the proceedings.

The book and the film both depict the hearings as a kangaroo court that had no respect for basic tenets of due process and fairness. The AEC panel formed to decide the issue had access to Oppenheimer’s massive FBI file, much of which contained evidence that had been collected without proper warrants. Crucially, Oppenheimer’s 1943 interview with Army officials over the Chevalier incident was secretly recorded and Oppenheimer’s attorney was never even furnished with a transcript.

In a trial, evidentiary rules exist to determine admissibility and to guarantee full disclosure, in advance, to both sides in a case. Such rules did not apply to the security hearing. Oppenheimer’s attorneys found themselves playing against a stacked deck week after week, constantly being blindsided by evidence that they did not even know existed. By holding the inquiry behind closed doors, Strauss was able to avoid creating a martyr for the scientific community which overwhelmingly backed Oppenheimer.

Through the course of the hearing, Oppenheimer’s relationships with CPUSA members during the 1930s were scrutinized, not in the context of the times, but with a Cold War mindset. Obviously, being a CPUSA member in the 1930s meant something very different than being a CPUSA member in the 1950s in the midst of the Cold War. Oppenheimer was not alone in this 1950s version of “cancel culture.”

It is difficult to point to a single reason for Oppenheimer’s security clearance being revoked, but the Chevalier incident was certainly a factor. By creating an impression of evasiveness during his interview in 1943, not knowing that he was being secretly recorded, Oppenheimer found himself contradicting prior statements eleven years later.

Hatred Destroys the Hater

The story of Lewis Strauss is yet another example of the futility of hatred. Strauss emerged victorious in 1954 by removing a powerful political opponent from his official role. But despite his attempts, Strauss could not remove Oppenheimer from his position at the Institute. Gradually, Oppenheimer’s reputation was rehabilitated.

Like many midterm elections, particularly during a president’s second term, the opposition gained seats in November 1958. In the Senate, the Democrats picked up thirteen seats previously held by Republicans and gained two additional seats from the new state of Alaska. When the Senate convened in early 1959, there were sixty-four Democrats and thirty-four Republicans. The election of 1960 was less than two years away and the Democrats were naturally looking for political advantage.

Two weeks before the midterm elections in 1958, President Eisenhower appointed Lewis Strauss as secretary of commerce. No cabinet official had been rejected by the Senate in over four decades, so Strauss felt confident in his chances when the Senate took up his nomination in 1959. However, the tables were about to turn.

The Strauss confirmation hearings centered on fairness of the Oppenheimer hearings. When Strauss recruited Oppenheimer to join the Institute in 1947, Oppenheimer had volunteered that there was “derogatory information” in his past. Strauss was aware of Oppenheimer’s history in left-wing politics and did not raise objections until the two men clashed over policy matters, with the H-bomb being the most important example. In his testimony during the hearing, Strauss often appeared evasive and disingenuous. He was publicly humiliated in a very close vote rejecting his nomination.

Conclusion

It is clear that J. Robert Oppenheimer was treated very poorly during the 1954 security hearing and that it was primarily driven by personal animus and policy disagreements rather than genuine questions about his patriotism and loyalty to the United States. Oppenheimer’s association with communists during the 1930s and early 1940s took place at a time when geopolitical alignments were far different than in 1954. However, his behavior was judged by the standards of a later period and he was “cancelled.”

This does not mean that Oppenheimer bears no responsibility for the situation. He clearly should have reported Chevalier’s approach immediately given his crucial role at Los Alamos and it should not have required a direct order to reveal the name. Inventing a “cock and bull” story to protect a friend was inappropriate and justifiably raised suspicions. However, the totality of the man’s record and accomplishments seem to far outweigh his misjudgments, and this should have been clear in 1954.

Although Robert Oppenheimer was partially rehabilitated from a political perspective in the 1960s, his security clearance was never reinstated and he never resumed his role in government. His death in 1967 at the age of sixty-two closed the book on the complex life of a brilliant man. It seems likely that a longer life might have brought greater vindication as the country moved into the 1970s and the United States and Soviet Union entered into arms control agreements.

Times change but human nature remains constant. The tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer should serve as a cautionary tale that we can still learn from today.

If you found this article interesting, please click on the ❤️️ button and consider sharing it with your friends and colleagues.

Thanks for reading!

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

American Prometheus, Chapter One, contains details on the Ethical Culture Society.

Depending on personality, it seems like young people either drift strongly toward the politics of their parents or rebel by going in the opposite direction. In Oppenheimer’s case, his close relationship with his parents appears to have resulted in political alignment.

American Prometheus, Chapter 14, covers the Chevalier incident in 1942-43 in detail.

American Prometheus, Chapter 17.