A Quarter Century of Investing

Lessons learned from twenty-five years of enterprising investing

One of the difficulties of active investing is that it is hard to measure competence except over very long periods of time. Investors cannot truly know if they are adding value above and beyond index funds until they have gone through at least one full market cycle, a process that usually takes many years.

In the short run, it is very difficult to separate luck from skill, although it is possible to judge a new investor’s thought process. I would think more highly of an inexperienced investor with a good thought process who happened to trail the S&P 500 last year compared to a speculator who somehow quadrupled his money in Fartcoin. Unfortunately, it is very possible for an investor to have a seemingly sound process but still fail to add value in the long run. Only time truly separates skill from luck.

My New Year’s Day tradition is to review investment performance over the past year. I will admit to feeling a brief boost to my ego if I manage to outperform the S&P 500, but I know that one year proves nothing, so my analysis also looks at my cumulative track record since I began actively investing using a value-oriented approach at the beginning of 2000. The end of 2024 marked a full quarter century, so I took more time than usual to assess the results.

When Warren Buffett announced that he was closing his investment partnership in a May 1969 letter to investors, he wrote that he did not know exactly what the future would bring, but he knew that he should not be pursuing the same activities at the age of sixty that he pursued at the age of twenty. He did not want to “be totally occupied with out-pacing an investment rabbit all my life.” While I have not been anywhere close to as successful as Warren Buffett, I feel the same way today and have far less of an inclination to actively manage my own account or to write about investing in public.

I have never presented my investment results in the past because I am a very private person and I have no desire to manage money professionally. However, I have been writing about investing for nearly sixteen years, in many cases about individual companies that I have invested in. In particular, I have written hundreds of articles about Berkshire Hathaway which has long been my most important investment. Readers might naturally wonder if the person writing these articles has had decent performance in his own portfolio over the years, so I have decided to post my personal track record in this article.

Before sharing the numbers, I need to emphasize that I am not trying to attract investor capital (I would decline offers to manage money professionally) and I am not trying to sell any kind of investment service. The numbers I am reporting are pre-tax and unaudited.

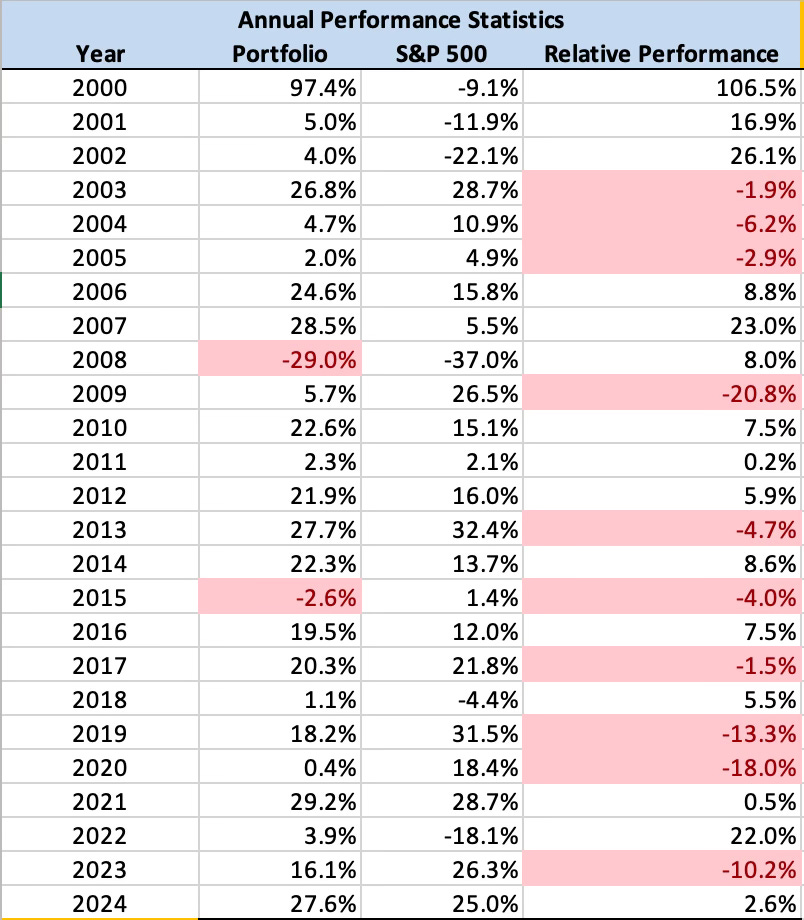

The table below shows my portfolio’s performance for each year, the total return of the S&P 500, and my relative performance. From 2000 to early 2009, I was a part-time investor with a demanding full-time job. In 2009, I retired from my job to focus on investing on a full-time basis and I started The Rational Walk at the same time. Over the past few years, I have been far less active in terms of managing my capital.

I should note that from 2000 to 2008, I regularly invested (dollar cost averaged) into a 401k plan through index funds while investing the majority of my after-tax pay in individual stocks. The performance statistics include only my individual stock picks, not the results of my 401k. In early 2009, I rolled over the 401k into an IRA, liquidated the index funds, and deployed the cash into individual stock picks.

As I wrote a few years ago in Pitfalls of Early Success, I actually started my investment journey in the second half of the 1990s, but it took me a while to adopt anything resembling a coherent value-oriented approach. My exposure to Warren Buffett’s letters and Benjamin Graham’s writings eventually caused me to “see the light,” and not a moment too soon. In early 2000, I sold my stake in more speculative stocks, most notably Intel, and became an investor in Berkshire Hathaway for the first time. I have to attribute luck rather than skill to my timing in 2000. I attended my first Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting and made investments in other beaten down value stocks that were left for dead during the dot com bubble. Unfortunately, I was working with a very small amount of capital at the time!

Looking at the big picture, I am most pleased with the fact that I posted negative returns in only two years while the S&P 500 posted negative returns in six years. However, looking at the long-run obscures how agonizing the short-run can be. The 29% loss for full-year 2008 might have been less severe than the decline of the S&P 500, but this masks the fact that my portfolio declined by nearly 50% from its peak in September 2008 to its bottom in March 2009. I made the decision to leave my job in September 2008 and when I walked out the door for the last time, my portfolio and net worth was a shadow of what it had been.

It is easy to look back at a graph of the stock market starting in 2009 and think that it was a no-brainer to back up the truck and buy at the time. I assure you that it was anything but obvious that early 2009 was the time to buy. Plenty of commentators thought that we were in for a second Great Depression and bearishness was pervasive. I’m proud of the fact that I wrote intelligently about coping with market meltdowns very close to the bottom tick. But while I did not panic and sell everything, I also became extremely risk averse. This cost me dearly as I underperformed the market as it snapped back later in 2009.

No one rings the bell at market bottoms, but it is usually true that the early stages of a bull market rewards the most precariously positioned companies. As it became increasingly clear that we were not in for a major depression, the lower quality names skyrocketed while the safer companies I opted for lagged far behind. In retrospect, it is easy to say this was a mistake. However, the real mistake was probably not finding another job for another year or two. Instead, having lost half of my peak capital base, I was extremely nervous until success in the mid 2010s made it clear that I was on a sustainable course.

It would be misleading to simply compound performance for a quarter century to come up with an average annual return of 14.3% because I was working with very small sums in the early years. However, it is good to observe that my portfolio’s dollar-weighted internal rate of return has been 12.5% over the quarter century, comfortably in excess of the performance of the S&P 500 based on a popular S&P 500 return calculator:

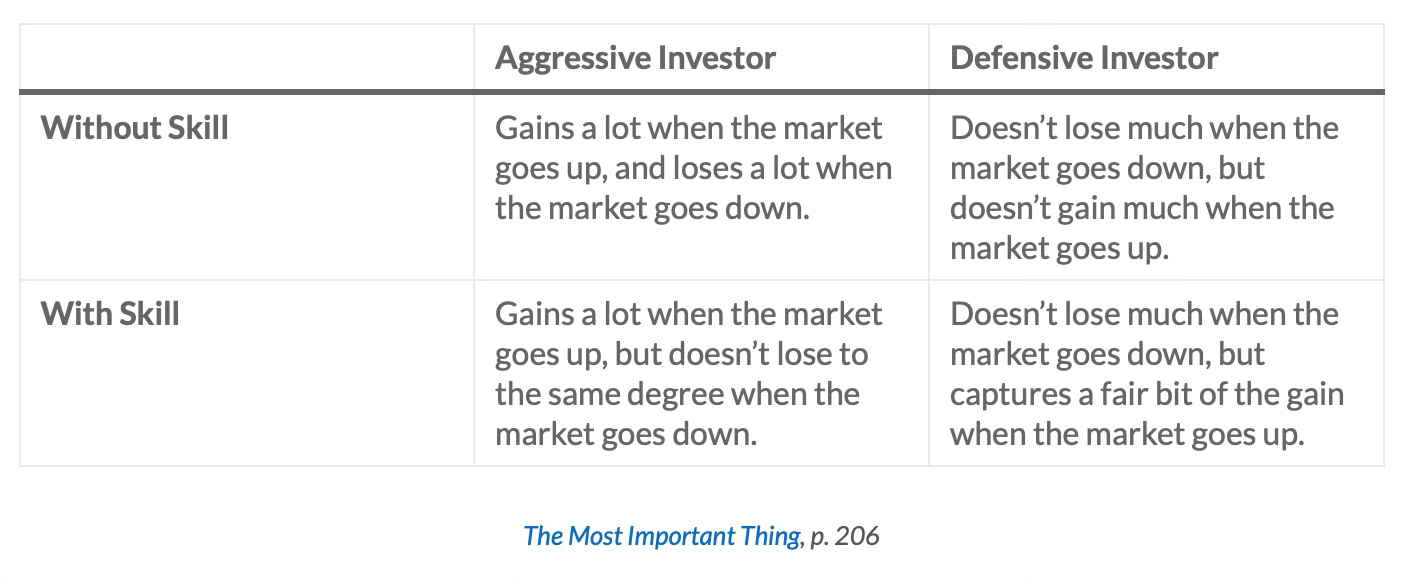

In The Most Important Thing, Howard Marks wrote about how we can determine whether an investor is adding value. The two-by-two matrix that he presented told the story in broad strokes:

Is a quarter century enough time to separate luck from skill? I like to think that I fall into the lower right hand quadrant of a defensive investor with skill. Obviously, there is no proof of skill. A lucky streak can go on for a very long time for certain individuals, but eventually most investors operating on luck alone will blow up.

If I have a certain amount of skill, it is reasonable to believe that active investing in the future could outperform the S&P 500, especially given the elevated valuation of the index in early 2025 which is even more extreme than when I wrote about the topic in early 2024. I am not about to sell my long-held investments and put the after-tax proceeds into the S&P 500 or any other broad-based index fund. I have a good understanding of what I own and believe my portfolio provides more value than the index, especially given the power of tax-deferred compounding. My plan is to basically “coffee can” my portfolio, although I remain open to acting if any of the dozen or so companies on my watch list fall to attractive levels.

Over the next quarter century, I care much less about whether I beat the S&P 500 than achieving reasonable real after-tax returns on my portfolio. I have zero desire to fly on private jets, own a Manhattan penthouse with a view of Central Park, a second home in Jackson Hole, or to consume the items that seem to drive most people in the investing world. While many readers would shrug at my net worth, it is sufficient when compared with spending desires. Far more importantly, it provides financial freedom and security, at least in terms of security that money is capable of buying.

It is interesting to reflect on whether I would make the same choices again if I could rewind back to 2000. I don’t think that very many people are lucky enough to have no regrets. I was far too obsessively focused on money for many years, especially while I still had a full-time job. My only goal was to accumulate enough to “retire” and manage my account on a full-time basis. I did not realize that the main problem was the specific employment situation that I was in, not being employed in general. Life would have been less stressful if I had taken another job in 2009 and worked for another five years. In retrospect, I did not leave enough of a margin of safety and the financial crisis and bear market of 2008-09 hit at exactly the worst time!

For investors considering embarking on active management of their personal funds, my advice is to take the process seriously on a part-time basis for at least a full market cycle to determine if you have demonstrable skill. Accumulate enough financial resources to avoid stress even if you face a fifty percent drawdown before starting to invest on a full-time basis. Remember that money is limited in terms of its utility. There are a huge number of things in life that cannot be purchased at any price. For this reason, even if you achieve great success financially, far in excess of your needs, it would be delusional to think that all of your problems will be solved. While I do not have money problems in 2025 thanks to my investment performance, I still have problems that cannot be addressed with money at all.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.