“I have great hopes in this direction for machines that will rival or even surpass the human brain. This area, known as artificial intelligence, has been developing for some thirty or forty years. It is now taking on commercial importance. For example, within a mile of MIT, there are seven different corporations devoted to research in this area, some working on parallel processing. It is difficult to predict the future, but it is my feeling that by 2001 AD we will have machines which can walk as well, see as well, and think as well as we do.”

— Claude Shannon, Kyoto Prize Speech, November 11, 1985

Claude Shannon is most famous for his groundbreaking work related to information theory and communications but he was also a multi-disciplinary thinker and a lifelong tinkerer. He was never satisfied with applying his genius to the abstract problems of pure mathematics, instead always striving to use mathematical concepts to solve concrete problems in multiple disciplines.

There is no Nobel Prize dedicated to mathematics, but Shannon received many other honors during his career including the Kyoto Prize in 1985. In his acceptance speech, he predicted that machines would soon surpass human capabilities. While he might have been too optimistic by a couple of decades, Shannon clearly could see the rise of machine learning and artificial intelligence on the not-too-distant horizon.

Thirty-five years before accepting the Kyoto Prize, Shannon developed one of the earliest examples of machine learning when he built Theseus, a mechanical mouse that could figure out its way out of a maze. Theseus had the ability to remember the architecture of a maze and figure out how to get to a piece of “cheese” at the end. Shannon proved that the mouse could learn by rearranging the contours of the maze and showing that Theseus could learn the new arrangement by trial and error.

Shannon demonstrated how Theseus works in this 1952 Bell Labs video:

While Shannon’s presentation is a bit stilted and not terribly impressive by twenty-first century standards, consider that this “intelligent” mechanical mouse was created over seven decades ago! It was based on telephone switching technology that Shannon worked with during his years at Bell Laboratories. Shannon created the Theseus mouse at his extensive home laboratory where he engaged in countless experiments just for the fun of gaining knowledge. He freely admitted that much of his time was spent on “totally useless things” of no apparent commercial value.

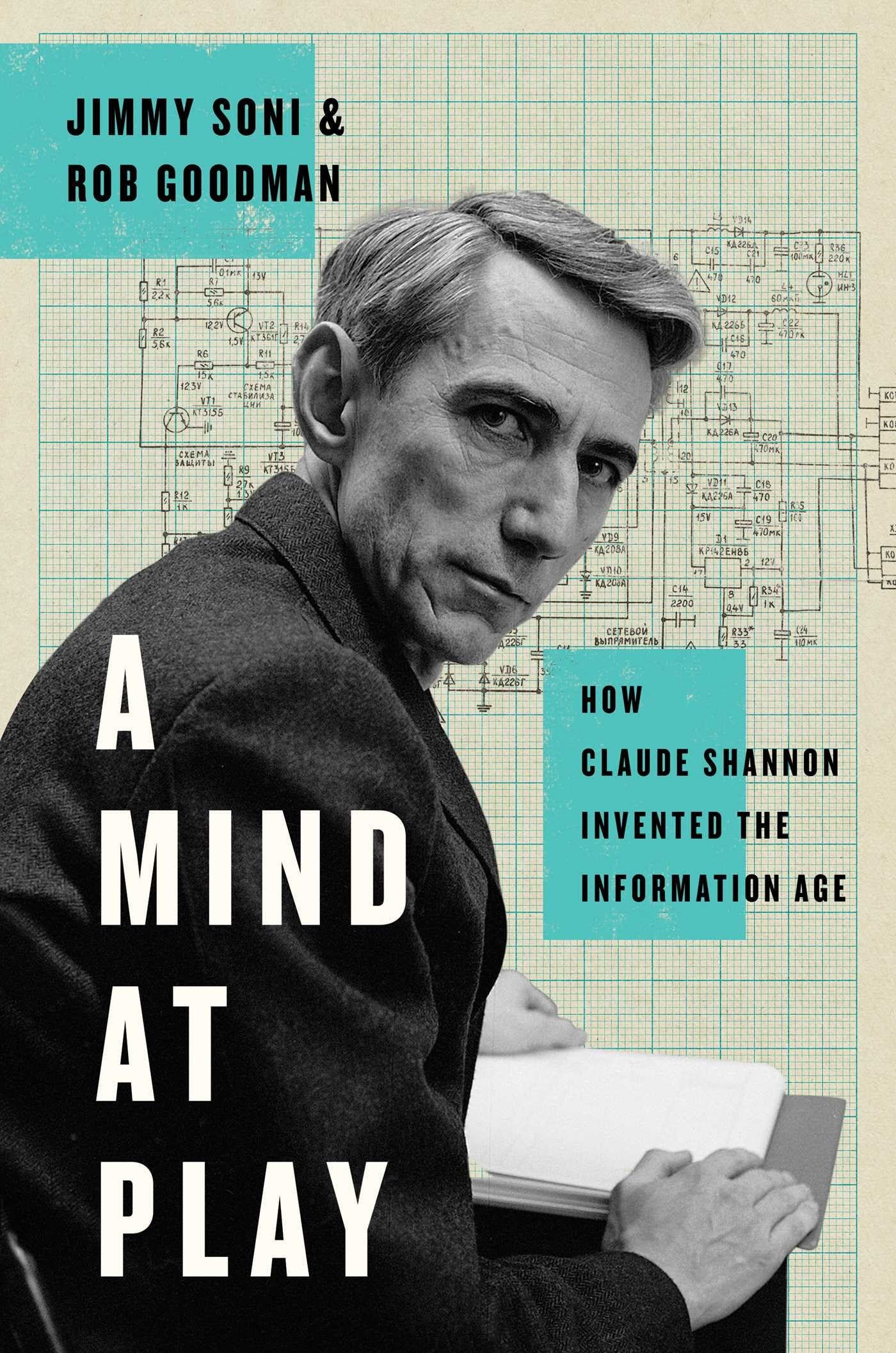

The reality is that the intense intellectual curiosity of a man like Claude Shannon is never directed in a “useless” manner because many discoveries are only recognized as important when looking back at history. Shannon’s playful attitude toward scientific inquiry combined with a good dose of eccentricity makes him a fascinating subject for a biography. In A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age, Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman present the portrait of a genius who saw no distinction between work and play. As Ed Thorp says on the back cover, Claude Shannon comes alive in the pages of this book.

My book spreadsheet indicates that I first read A Mind at Play in September 2017, a few months after I read Ed Thorp’s autobiography, A Man for All Markets. There is no doubt that I selected Shannon’s biography because I read about his association with Ed Thorp in A Man for All Markets.

I wrote an article about of A Man for All Markets but for some reason I did not write about A Mind at Play. When I recently realized this oversight, I decided to re-read A Mind at Play and put together some thoughts. With all the excitement over artificial intelligence, going back to Shannon’s life seems timely and appropriate.

Information Theory

The vast amount of information we encounter in our everyday lives is something that people under thirty-five simply take for granted because they cannot recall a world without the internet. For those of us who are a decade or two older, the rise of the internet looms large in our memories as a demarcation point. In my case, the internet went mainstream shortly after I graduated from college in 1995.

By the late 1990s, students and researchers went from microfiche to the worldwide web. By the mid-2000s, the internet was thoroughly mainstream although somewhere short of universal. The introduction of the iPhone in 2007 and the subsequent rise of the smartphone industry represented the democratization of the internet. By the early 2020s, 85% of Americans carried a supercomputer in their pockets.

As Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman write at the end of the book, “there is something ungrateful and grasping in enjoying our bounty of information without bothering to understand how it got here.”